The revolutionary beginnings of the South China Morning Post

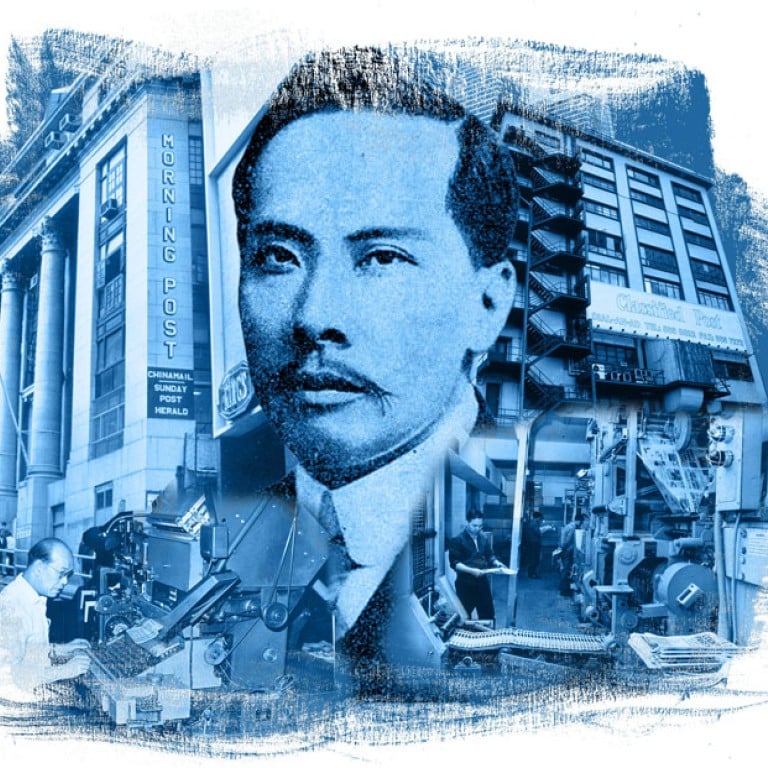

Tse Tsan-tai, co-founder of the South China Morning Post, was a key figure in the revolt that swept China at the dawn of the 20th century

When the first edition of the hit newsstands on November 6, 1903, its co-founders Tse Tsan-tai and veteran journalist Alfred Cunningham could hardly have imagined that it would eventually become an influential English-language newspaper in Hong Kong and the Asia-Pacific region.

But at the turn of the 20th century, there were already several English-language newspapers vying for just a few thousand readers in Hong Kong who were literate in English.

Andy Tse Kwok-cheong, grandson of Tse Tsan-tai, said running the was by no means a profit-making undertaking for his grandfather, given the limited English readership at the time.

"From a marketing point of view, the newspaper stood a high chance of suffering losses in the first few years, if not decades, of its establishment. Why the hell did Tse Tsan-tai found this 'South China Newspaper'?"

Before striking out as a newspaper man, Tse Tsan-tai, the son of a trader who had emigrated to Australia from Guangdong, was already a successful merchant who served as the comprador - or buyer - of Boyd, Kaye & Co and Shewan, Tomes & Co, two important local businesses.

In 1898, Tse, who sometimes went under the name James See, founded the Chinese Club, the Chinese business community's answer to their exclusion from existing clubs by whites.

Among the celebrities who joined the club were Li Ki-tong, a prominent businessman; Sir Ho Kai, a barrister and the first Chinese to become an executive councillor, and Sir Robert Ho Tung, chief comprador of Jardine Matheson.

Andy Tse said his grandfather believed he could boost his social standing in the colony through operating a decent Englishlanguage newspaper.

But there was another, secret reason for establishing the - revolution.

The became a platform for advocating the reform movement in China through writing and publishing commentaries on the cause. In effect, Tse turned the fledgling newspaper into the printing house for the Chinese revolution.

"By running the , my grandfather could have his own printing facilities, including lithographic printing machines, which he could use to print leaflets and posters to promote the revolution," said Andy Tse.

Tse was born in 1872 in Sydney. His patriotism had its roots in his family.

As a child, his father Tse Yet-chong told him the story of the cruel conquest of China by the Manchus. Tse Yet-chong was also leader of the Chinese Independence Party of Australia.

"I promised him [Tse's father] that when I grew up, I would return to China and do my best to help in driving the usurping Manchu Tartars out of China," Tse Tsan-tai wrote in his book , published by the in 1924.

According to Andy Tse, Tse Yet-chong was a leader of Hong Shun Tang, the Chinese Freemasons or the Hongmen Society, in southern China, which aimed to overthrow the corrupt Qing dynasty by force.

"That was why our family could easily mobilise activists to take part in armed revolts," said Andy Tse.

Aged 15, Tse Tsan-tai returned to Hong Kong and enrolled in Queen's College. Upon graduation, he joined the government's Works Department and worked there for 10 years.

In 1892, Tse and his friend Yeung Kui-wan founded the Literary Society for the Promotion of Benevolence, or Furen Wenshe. The association, with its headquarters on the first floor of 1 Pak Tsz Lane, Central, was ostensibly a study group that commented on social issues.

In reality, it was the first revolutionary organisation in Hong Kong. They joined with Sun Yat-sen when the latter came to Hong Kong in 1894, forming the Hong Kong Hing Chung Wui.

Between 1895 and 1903, Tse devoted most of his time to raising funds for the Hing Chung Wui, which made its first attempt to capture Guangdong in 1895. Yeung was elected president of a "provisional government", but the uprising failed miserably, as did another aimed at capturing Huizhou in 1900.

Sun subsequently led the revolution of 1911 and became the founder of modern China. The Qing court ordered the assassination of Yeung at his home at 52 Gage Street in 1901.

In 1903, Tse plotted with Hung Chuen-fook, brother of Hung Hsiu-chuan - the "king" of the "Taiping heavenly kingdom" - in a failed attempt to capture Guangzhou.

The Taiping rebellion against the Qing dynasty had been bloodily suppressed in 1864.

Andy Tse said his grandfather played a pivotal role in equipping and training revolutionaries for the armed insurgency against the Qing dynasty.

"As his family had a long history in trading, Tse smuggled arms and ammunition to Hong Kong from various places. The guns were covered by cement when they were shipped to Hong Kong," he said.

The history of his grandfather's revolutionary activities were passed on to later generations orally, Andy added. Tse Tsan-tai also used his private yacht to send revolutionaries to Red Tower in Tuen Mun, owned by prominent businessman Li Ki-tong, to take part in military training.

From the beginning, Tse did not have a good impression of Sun. In , Tse recalled his first impressions of Sun, describing the man as a "rash and reckless fellow".

"He would risk his life to make a name for himself. Sun proposes things that are subject to condemnation - he thinks he is able to do anything, no obstructions!" he wrote.

Tse added that he could not trust Sun with the leadership of the revolutionary movement. "I believe Sun wishes for everyone to listen to him. This is impossible, as his experience shows that it would be risky to rely solely on him," he wrote.

The rift between Tse and Sun never fully healed. Sun later founded another revolutionary society, Tung Meng Wui, but Tse declined to join.

In 1899, Tse produced a drawing, , widely regarded as the first political cartoon by a Chinese.

It portrayed the scramble of the Great Powers for influence in China in the late 19th century, and has been widely cited in history textbooks in Hong Kong.

Tse died, aged 66, in 1938 and was buried in the Chinese Christian Cemetery in Pok Fu Lam.

Andy Tse, a retired town planner from the Planning Department, said his grandfather's unwillingness to work with Sun later in his revolutionary career was one reason Tse was not more widely recognised today.

"The past century has witnessed the rise and fall of many newspapers in Hong Kong," said Andy Tse.

"It has been a huge achievement for the to survive for the past 110 years."