Analysis | Hong Kong's youngest activists draw inspiration from political liberalism

Over breakfast at a sandwich place in Kowloon Tong, three of Hong Kong’s most famous student activists are talking about their roles in Occupy Central. Like all students, Joshua Wong Chi-fung and Agnes Chow Ting, both 18, and Alex Chow Yong-kang, 23, talk about problems within the government and the need for greater social justice.

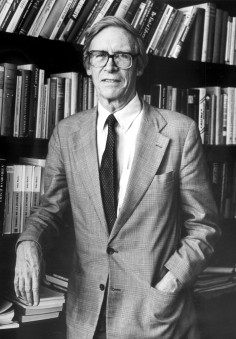

They draw on philosophical arguments as justification, but unlike their counterparts in the West, who might quote left-wing thinkers like Noam Chomsky and Slavoj Zizek, these students openly admire John Rawls, a postwar American political philosopher most famous for writings on political liberalism and justice.

In America, Rawls is still considered a prominent philosopher and a staple of undergraduate philosophy courses, but his writing is typically not at the forefront of mass protest movements.

Wong says he can’t wait to read Rawls at university.

Less than a week after an interview with the South China Morning Post, both Wong and Agnes Chow Ting obtained results better than the university entry requirements in the Diploma of Secondary Education exams. However, Wong has said he was disappointed with some of his exam results and plans to appeal.

Rawls’ significance to Hong Kong students, particularly those involved in activism, speaks volumes about the city’s unique political and social traditions.

Hongkongers take great pride in their legal system, inherited from the British tradition, as well as as the strength of the city’s rule of law. It is also something many here fear losing when the “one country, two systems” policy ends in 2047.

Watch: Students respond to Carrie Lam's report on universal suffrage for Hong Kong in 2017

The students seem to have realised that it is these kinds of traditions they have to appeal to if they want to see Hong Kong’s pro-democracy movement succeed. They will also have to tap into it to convince the city's relatively conservative populace to take part in the next phase of Occupy Central.

“If you ask Hong Kong people if they think that rule of law is important, they will say it is very important,” said Agnes Chow Ting. “The thing is, different Hong Kong people have a different definition of rule of law. For us, as activists, we think that rule of law is that the law itself has to show justice.”