Unsung warriors set up in Sai Kung: the Hong Kong guerrilla fighters who battled the Japanese in WW2

On December 8, 1941, Hong Kong became one of the first battlegrounds in the Pacific campaign of the invading Japanese. On the same morning as the attack on Pearl Harbour, Japanese forces attacked British Hong Kong without any prior declaration of war. Japan's act of aggression was met with fierce resistance but the colony fell after 18 days of intense fighting. For three years and eight months, the people of Hong Kong lived under Japanese Occupation. This is one of a series of stories in remembrance of the Battle of Hong Kong and the dark days that followed.

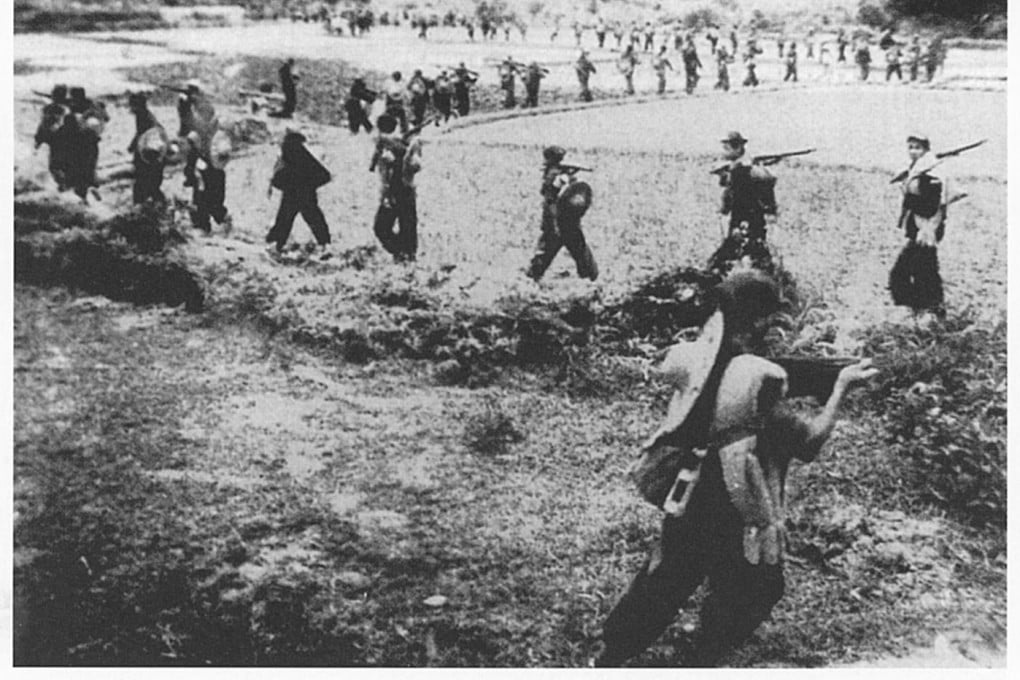

Even as the British colonial government surrendered after 18 days of fierce fighting in the Battle of Hong Kong in December 1941, a group of young men and women refused to bend.

Barely two months after the surrender, the Hong Kong and Kowloon Independent Brigade was formally set up on February 3, 1942 at Wong Mo Ying Chapel, Sai Kung. It was put together by the Chinese Communist Party, then an uneasy ally of the mainland's ruling Kuomintang in the fight against the Japanese.

The brigade was later designated as the local branch of the East River Column, comprising Communist guerillas who hailed from Guangdong during the war. Many of the Hong Kong recruits were young Hakka villagers from the New Territories.

Watch: Hong Kong guerrillas during World War II - East River Column: Part 1

According to East River Column, a book written by former Sai Kung District officer Chan Sui-jeung, the brigade had nearly 5,000 full-time soldiers by mid-1943.