Former Hong Kong policeman seeks baby he saved in tragic 1980 incident at sea that claimed lives of 48 illegal immigrants

Leslie Bird was highly commended for his bravery that cold February night, but he could not rescue child’s mother from sinking boat, a fact which has haunted him through the decades

Terrified cries rang out through the predawn gloom across the rough sea. Bone-weary and freezing, Inspector Leslie Bird of marine police launch 56 was functioning only on adrenaline when he dived back into the dark winter waters off Lantau Island.

A junk boat carrying illegal immigrants had capsized, and he had already saved the life of a seven-month-old baby boy, but the child’s mother was still out there among the wreckage.

Shrugging off exhaustion, Bird surged through the swell to where he could make out the woman, aided only by a searchlight from his vessel. He reached her, and for a brief second, it seemed as though he had her within his grasp, but the waves pulled them apart.

Bird has been left with the haunting image of the woman he almost saved, as the treacherous depths dragged her under that cold night.

Some 48 Chinese illegal immigrants lost their lives in the sinking on February 5, 1980.

Four stranded on yacht saved by police in heroic sea rescue during Mangkhut

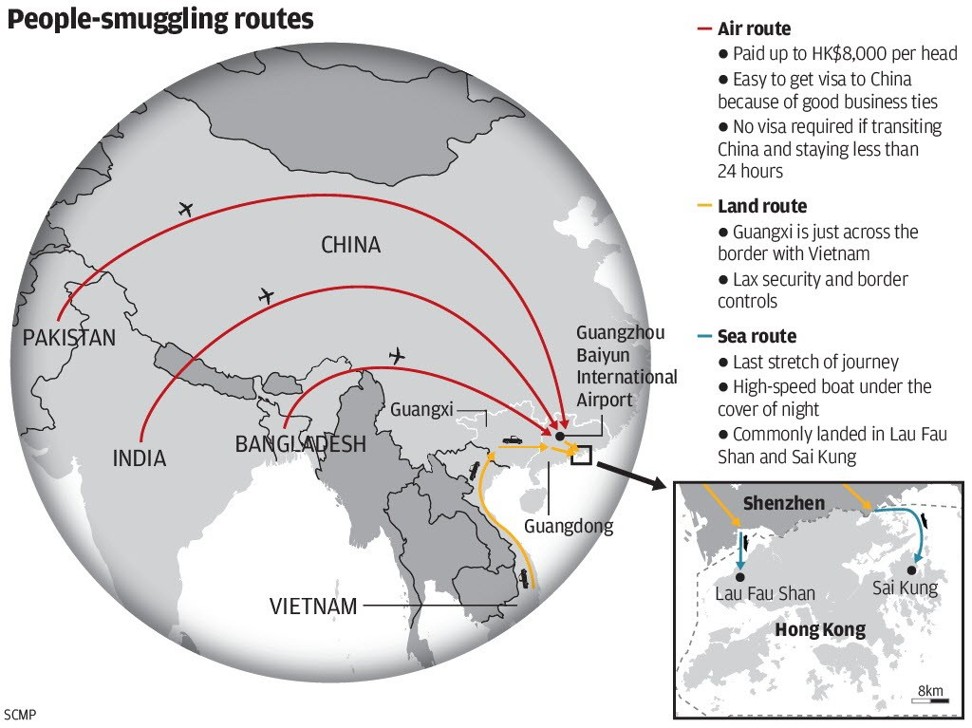

Mainland Chinese gangsters – known as snakeheads – that smuggle people across borders, ran a lucrative trade charging passengers for the dangerous journey to the then British colony of Hong Kong.

That morning, the strong monsoon signal was in force, and the rickety vessel was no match for the heavy winter swell.

The police launch commanded by Bird was the first on the scene when the 40-foot junk capsized.

“She wasn’t more than an arm’s length away,” he says. “Her hand was right there.

“In those last seconds she just seemed to slip away. I had this feeling of powerlessness.”

Eight crew saved after abandoning sinking barge at height of storm

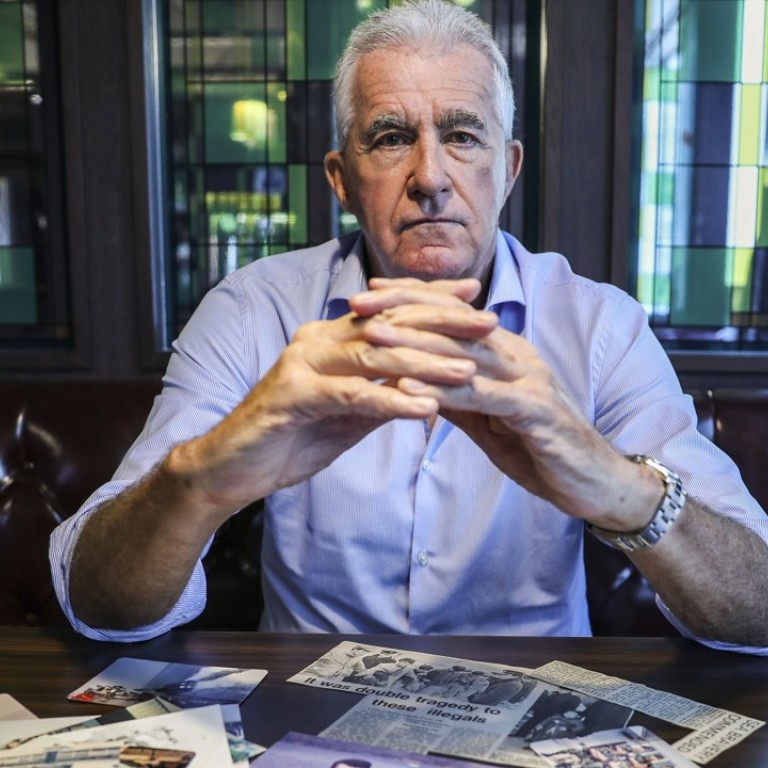

Now based in Hong Kong, the 66-year-old is on a mission to find the child whom he had saved, the renewed drive prompted by an award from a British charity.

“I saw his mother drown in front of me,” he says. “That has stayed with me. If he is out there, and wants to know more about what happened, I want him to know that I’m here, in Hong Kong.”

I saw his mother drown in front of me … That has stayed with me

Back then, the Royal Humane Society in London (RHS), a charity that grants awards for acts of bravery in life saving, presented Bird with a testimonial on parchment for saving the baby.

But Bird realised he had misplaced the document over the years, and he applied to the society for a replacement, which he collected in August.

“I thought I’d just be picking up a testimonial from them,” Bird says.

Instead, the staff at RHS sat Bird down and asked if they could talk through the incident. They informed Bird that the 1980 rescue had earned him not one, but two awards: the second for his resuscitation of the child.

The baby was not showing any signs of life after Bird plucked him out of the water. He gave the child mouth-to-mouth resuscitation and after an agonising few seconds, the boy vomited and began wailing, much to rescuers’ relief.

It’s pretty unusual to give two awards to the same person for one incident

That was when Bird jumped off the launch to search for the boy’s mother.

“It’s pretty unusual to give two awards to the same person for one incident,” RHS assistant secretary John Wilson says. “But Leslie also put his own life at risk to save another, and that selflessness should be recognised.”

In typewritten documents seen by the Post, the commissioner of police wrote to the RHS in 1980 with a summary of the incident, recommending Bird for a testimonial on parchment combined with a resuscitation certificate. That certificate never reached Bird.

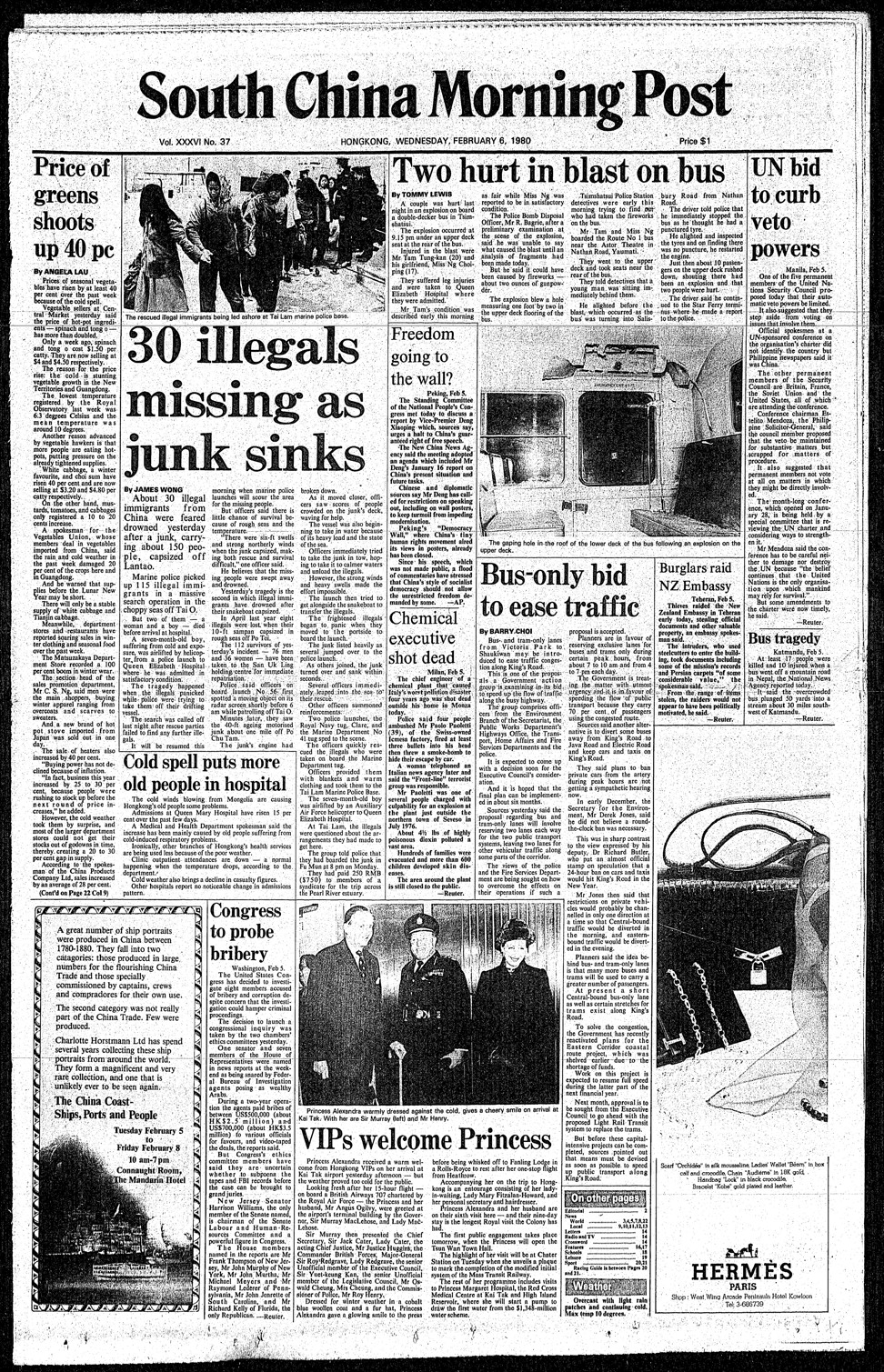

On February 6 that year, the Post reported on the incident, mentioning that a seven-month-old boy was airlifted to Queen Elizabeth Hospital. Other news reports pegged the number who perished in the accident to 48, with 112 rescued.

According to the Post report, the survivors told police they paid 250 yuan – about HK$750 then – to members of a syndicate for the trip from mainland China.

Bird says that while he has lost count of the rescues he made throughout his police career, this one was different. Bringing a child back to life and then seeing his mother drown, he says, had affected him in ways he still does not fully comprehend.

Fewer illegal immigrants arrested in Hong Kong after joint crackdown on people smugglers

But Bird believes finding the boy will help him come to terms with his internal struggle.

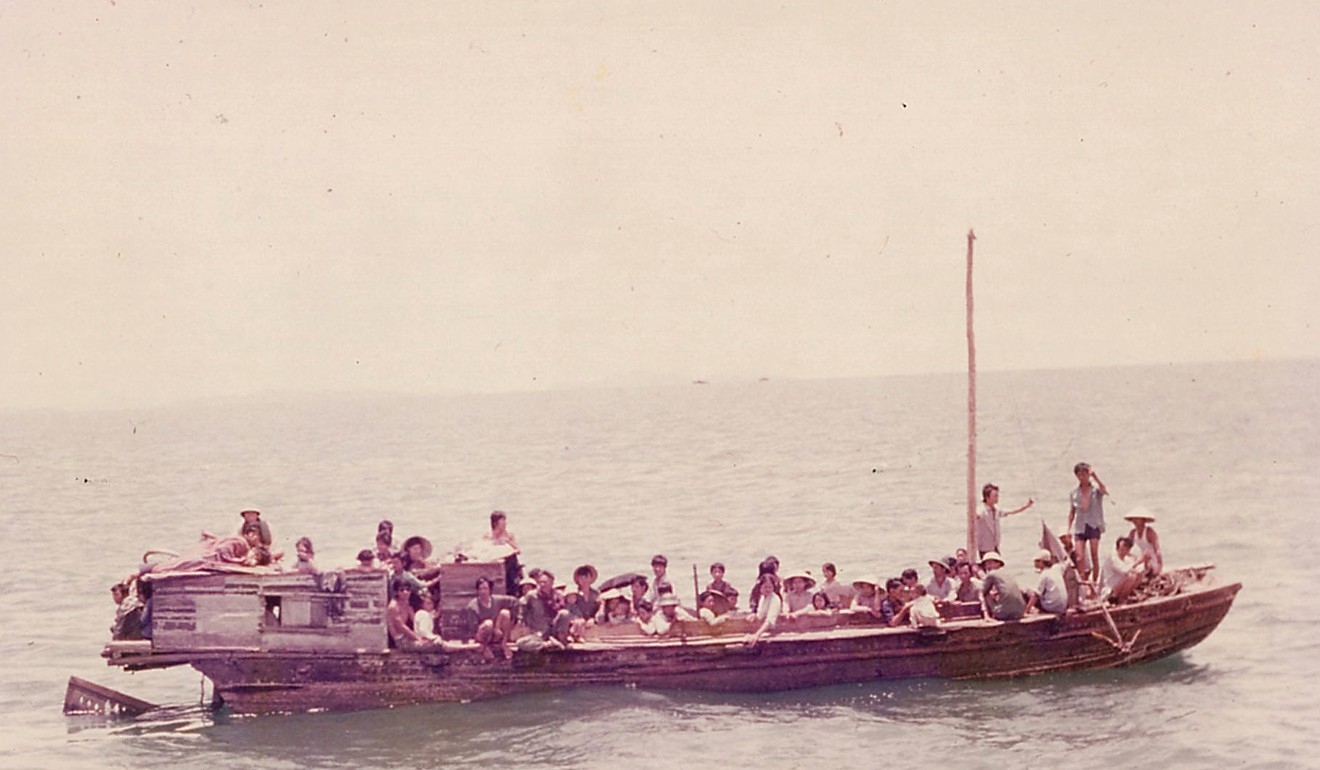

The incident took place just after the height of the boatpeople era, which, as historian Carina Hoang recounts, was a tumultuous episode in Hong Kong’s history. “The government was really learning as it went along,” says Hoang, herself a Vietnamese boatperson. “They weren’t at all prepared for this emergency.”

John Carroll, a professor at the University of Hong Kong’s history department, says: “It was widely publicised at the time how hard-pushed Hong Kong’s frontline security services were in dealing with the boatpeople situation.”

In all, it is estimated that 230,000 Vietnamese boatpeople made it to Hong Kong between 1975 and 1997. As Hoang notes, the Hong Kong authorities were overwhelmed. The exodus was caused by the fall of Saigon to North Vietnamese forces.

But the people Bird and his crew saved that night were not Vietnamese: they were Chinese, from Guangdong province. On questioning those rescued, police established that the boat had come from Humen town, just to the northwest of modern-day Shenzhen.

When it came to snakeheads profiting off smuggling people from mainland China into Hong Kong, Carroll says the reason some were tempted to make the dangerous journey was for the possibility of gaining Hong Kong citizenship.

He notes the Hong Kong government’s Touch Base Policy, introduced in 1974, enabled Chinese immigrants to stay in the city if they could fulfil certain conditions.

Those who made it south of Boundary Street, which cuts across Kowloon just to the north of the Prince Edward area, and could prove they had relatives who were Hong Kong citizens, were eligible to register for a Hong Kong ID card.

Those apprehended north of Boundary Street or in Hong Kong waters, however, were repatriated to mainland China immediately.

Snakehead gangs from southern China are thought to have started smuggling people into Hong Kong in the 1960s, during the Cultural Revolution. From 1979 to 1980, about 200,000 illegal immigrants attempted to enter the city and were repatriated by authorities, while about 160,000 successfully claimed Hong Kong residency under the Touch Base Policy.

Hong Kong police round up illegal immigrants and their snakeheads hiding in Shek O hills

But as living standards in mainland China have risen, the number of illegal immigrants from across the border has dipped with authorities suspecting most of them are coming through checkpoints on land.

Meanwhile, Hong Kong police reported while snakehead gangs were still active, fewer were venturing into the city’s waters compared with previous decades as a result of stricter enforcement and heavier sentencing for offenders.

Superintendent Timothy Worrall from the force’s Small Boat Division says “operations to combat illegal immigration are a priority”, and adds these are done in tandem with mainland Chinese authorities.

“The strategy is effective not only in the detection and apprehension of illegal immigrants themselves, but also against the syndicates that arrange their passage,” he says.

Worrall says his department intercepted 438 illegal immigrants from Shenzhen, Shekou and Zhuhai, equivalent to “27.1 per cent of all illegal immigrants arrested in Hong Kong” last year.

A police spokesman says the force has no information on the 1980 case.

Mahathir’s return sparks memories of Vietnamese boatpeople and Hong Kong’s humanity

Of those rescued that night, Bird says almost all were deported. He assumes the boy was one of the few who was not sent back because he was taken to Queen Elizabeth Hospital, which was within the zone under the Touch Base Policy.

While news reports at the time said the hospital confirmed the child survived, no present-day records of the boy are available.

A Hospital Authority spokeswoman says Queen Elizabeth is “not able to trace the record” for the child because rescuers and staff had not known – and therefore did not record – the boy’s name.

As his mind wanders back to that fateful night, Bird says the water was teeming with people thrashing around the sinking junk. He had spotted the woman clinging to a section of the vessel, and next to her, among the wreckage, was her baby.

I’m here to answer any questions he may have, if he chooses to come forward

“I recall the face of the woman, though it was dark. She was young,” he says. “We were face to face for no more than a split second.”

The baby, Bird noted, wasn’t moving.

The woman, panicking, struggled away as Bird tried to help her, so he turned his attention to the baby, drawing him to his chest, and swam back to the launch.

After reviving the child, he went back for the mother. It would be the last time he would see the boy.

In spite of this, Bird has not given up hope of contacting the survivor, who by now would be around 39 years old. His hope, he says, is that making the story known might encourage survivors of the February 5 incident to come forward.

Bird says he has not thought about what he would say to the man should they meet.

“I’m here to answer any questions he may have, if he chooses to come forward. Who knows? We could be living on the same street.”