Revolution always on the mind of South China Morning Post co-founder Tse Tsan-tai

Driving force behind establishment of newspaper did not see it as just commercial endeavour, it became platform for advocating the reform movement

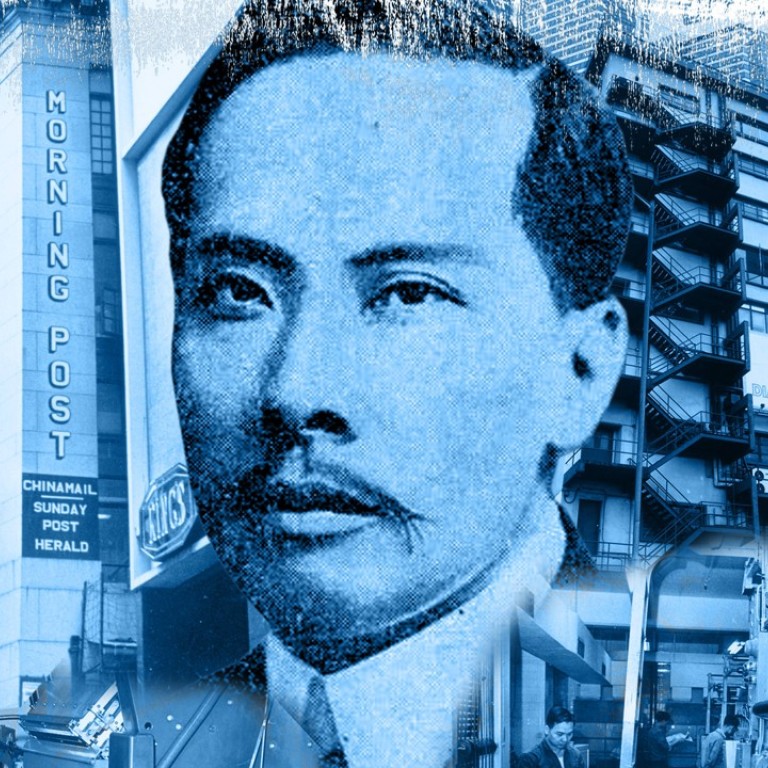

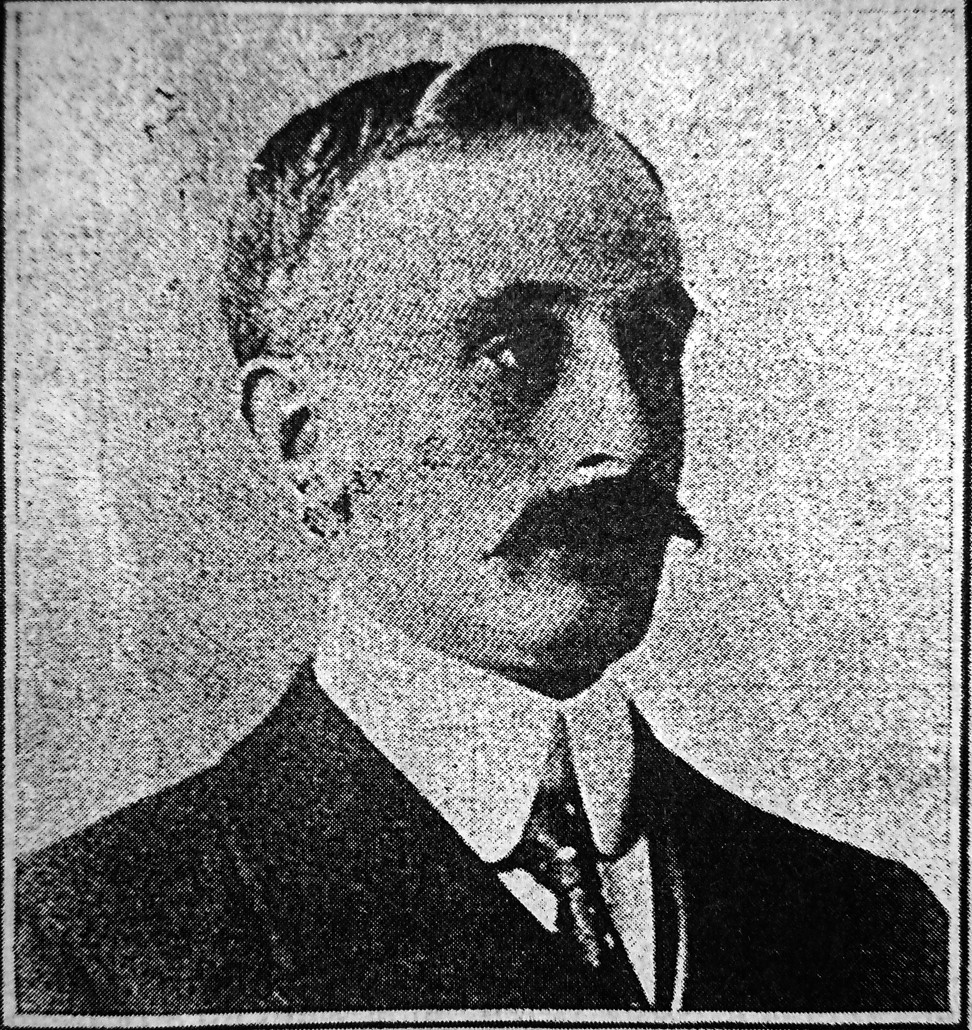

The South China Morning Post, a leading English-language newspaper that has reported on Hong Kong, China and Asia for more than a century, might not have come into existence if its co-founders, Tse Tsan-tai and Alfred Cunningham, had only profits or commercial viability on their mind.

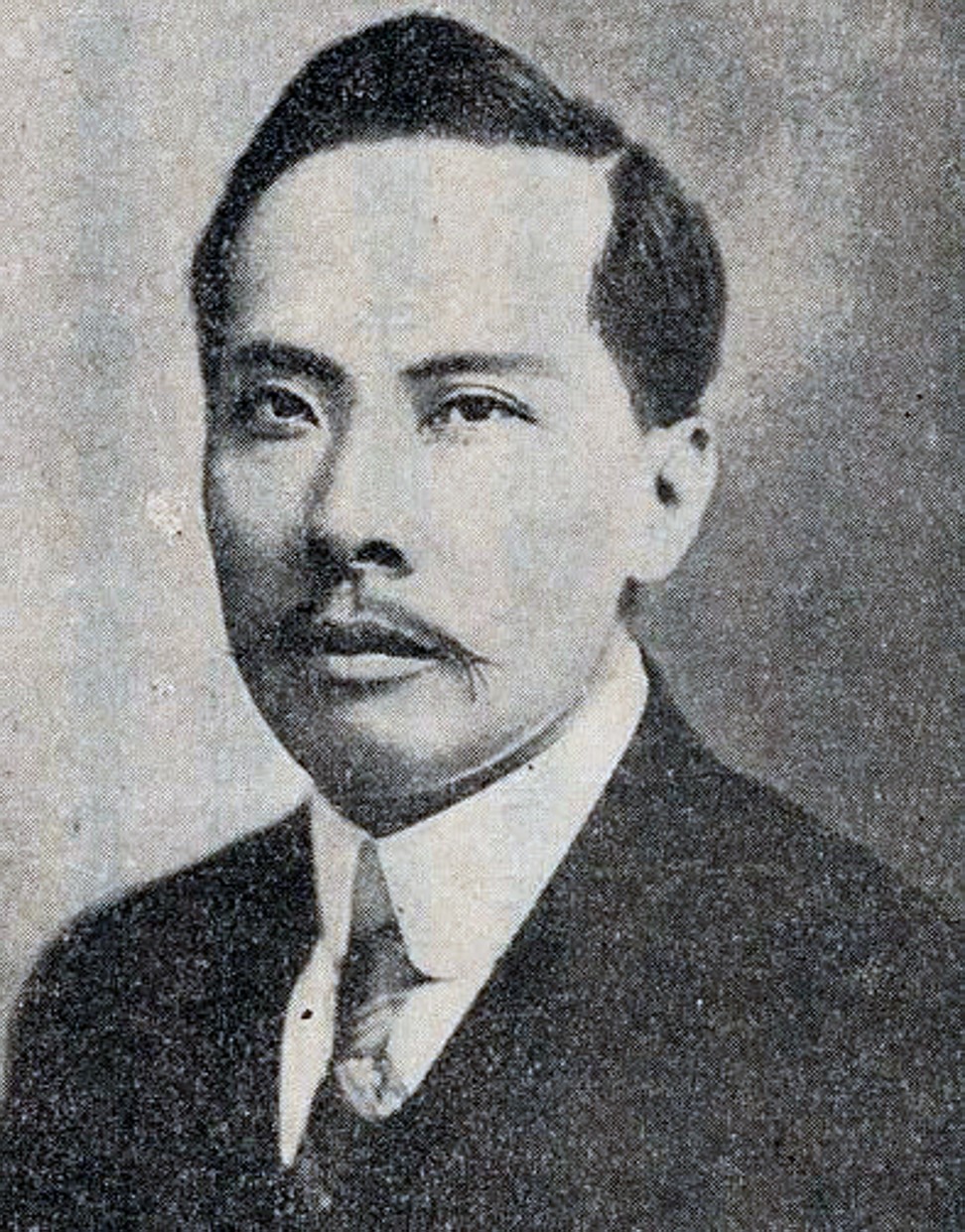

Tse’s colourful life went beyond running a newspaper and making business deals, which he was adept at, before teaming up with Cunningham, a veteran British journalist, to found the Post.

Tse was also a political cartoonist and inventor, as well as one of the first liberals calling for democratic reform in Hong Kong.

At the turn of the 20th century, Hong Kong had three English-language newspapers vying for the few thousand readers in the city literate in English. China Mail, established in 1845, was the oldest and by far the most popular in the colony. The other two were the Daily Press and Hongkong Telegraph.

Andy Tse Kwok-cheong, grandson of Tse, said much about the Post’s was still unknown and some basic questions had been left unanswered.

“Nobody in his right mind would have come up with the idea of founding an English-language newspaper at the time,” he said. “Why on earth did my grandfather found this newspaper, when the readership and market was so limited?”

Tse Tsan-tai was financially backed by his father Tse Yet-chong – who made a fortune running an import and export company in Sydney – and the pair did not see the newspaper as a purely commercial endeavour.

The revolutionary beginnings of the South China Morning Post

“Tse Tsan-tai and his father well knew the importance of using English mass media to make an impact in Hong Kong and overseas,” Andy Tse said.

Father and son had their eyes on something much bigger – revolution in China. The Post became a platform for advocating the reform movement through writing and publishing commentaries on the cause.

By running the Post, Tse said his grandfather could purchase lithographic printing machines, which he could use to create posters and leaflets espousing revolutionary ideals.

“My grandfather monitored the process of printing those materials. The staff couldn’t say anything as it was the boss’s orders,” he said.

According to Tse, the newspaper’s printing press had been used for underground activities before the South China Morning Post Company was established in January 1903 – printing posters to promote an uprising in Guangzhou against the Qing dynasty.

Tse Tsan-tai teamed up with Hung Chuen-fook, nephew of Hung Hsiu-chuen – the “king” of the “Taiping heavenly kingdom” also known as Hong Xiuquan – to plot an uprising to capture Guangzhou in January 1903. Li Ki-tong, a rich Hong Kong merchant, provided financial support. The Taiping Rebellion against the Qing dynasty had been bloodily suppressed in 1864.

“The posters used for the planned uprising in Guangzhou were printed in the Post’s plant,” Andy Tse said.

His grandfather also arranged for Hung to organise military training for revolutionaries, with Tse using his private yacht to send them to Red Tower in Tuen Mun, and his estate in Tsuen Wan.

On January 25, 1903, the plotters’ headquarters – a building named Hejizhan – at 20 D’Aguilar Street in Central, was raided by Hong Kong police. The raid began soon after Hung and Tse’s younger brother, Thomas Tse, left for Guangzhou to direct the armed insurgency.

The Guangzhou uprising failed, and provincial authorities arrested hundreds of revolutionaries.

“It is regrettable that the 1903 uprising is not better remembered today. It is not mentioned in many books on modern Chinese history,” Andy Tse said.

Andy Tse, a retired town planner at the Planning Department in Hong Kong, who now lives in Canada, said the history of his grandfather’s revolutionary activities had been passed down to later generations orally.

Before striking out as a newspaper man, Tse Tsan-tai was already a successful merchant who served as the comprador – or buyer – of Boyd, Kaye & Co, and Shewan, Tomes & Co, two important local businesses.

Tse Tsan-tai was born in 1872 in Sydney, where his father, Tse Yet-chong, was a leading Chinese merchant who had emigrated there from Guangdong, and the leader of the Chinese Independence Party of Australia.

According to Andy Tse, Tse Yet-chong was a leader of Hong Shun Tang, the Chinese Freemasons, or the Hongmen Society, in southern China, which had aimed to overthrow the Qing dynasty by force. When Tse Tsan-tai was a child, his father told him the story of the conquest of China by the Manchus.

Aged 15, Tse went to Hong Kong to join his father, who was doing business in the colony. He was enrolled in Queen’s College, and joined the Works Department after graduating from the elite school in 1890.

Nobody in his right mind would have come up with the idea of founding an English-language newspaper at the time

In 1892, he and his friend Yeung Kui-wan founded the Literary Society for the Promotion of Benevolence, or Furen Wenshe. The association, with its headquarters on the first floor of 1 Pak Tsz Lane, Central, was ostensibly a study group that commented on social issues.

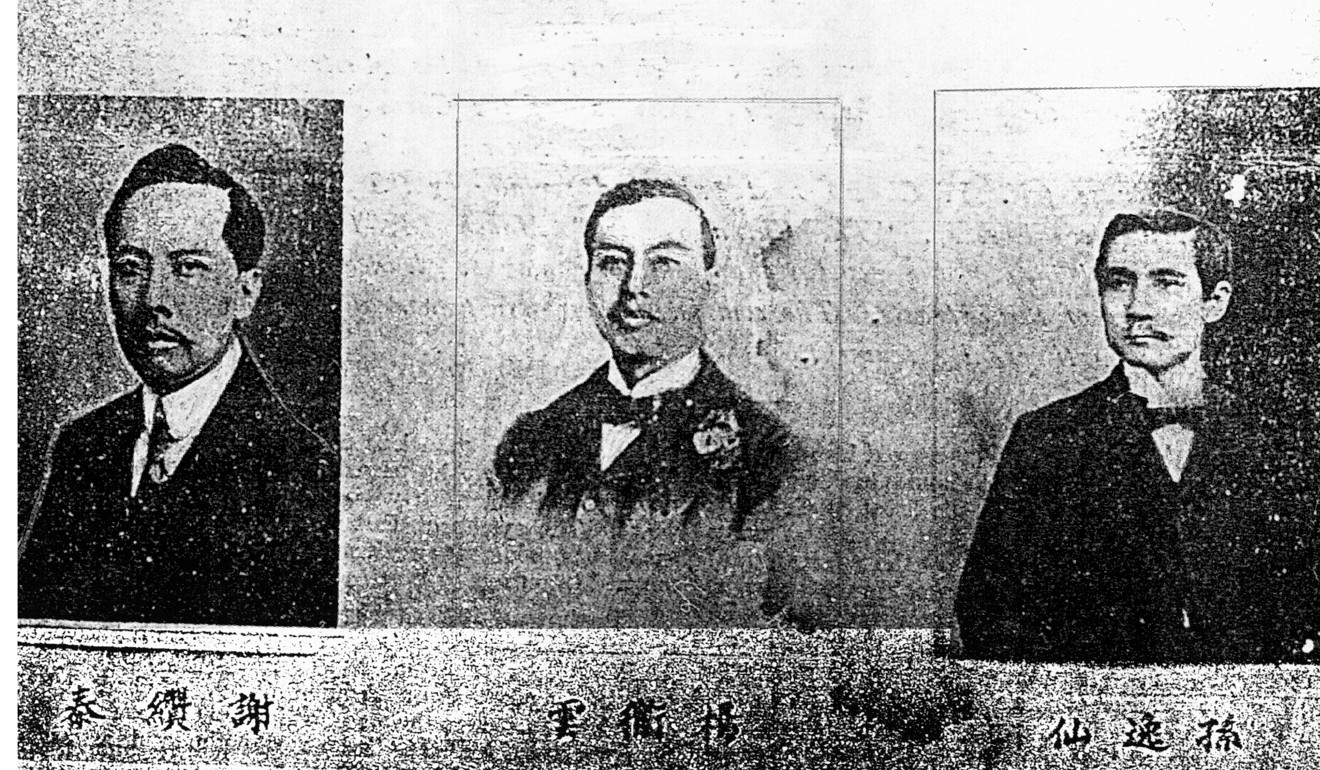

In reality, it was the first revolutionary organisation in Hong Kong. They joined with Sun Yat-sen when the latter came to Hong Kong in 1894, forming the Hong Kong Hing Chung Wui, or the Society for the Restoration of China.

Between 1895 and 1903, Tse devoted most of his time to raising funds – and smuggling firearms and ammunition to Hong Kong – for the Hing Chung Wui, which made its first attempt to capture Guangdong in 1895. Yeung was elected president of a “provisional government”. But the uprising failed miserably, as did another aimed at capturing Huizhou in 1900.

Tse subsequently fell out with Sun, the man who led the revolution of 1911 and became the founder of modern China. Tse recalled his first impressions of Sun, describing the man as a “rash and reckless fellow”, in his book The Secret History of the Chinese Revolution, published by the Post in 1924.

“Sun proposes things that are subject to condemnation – he thinks he is able to do anything, no obstructions!” Tse wrote.

Tse added that he could not trust Sun with the leadership of the revolutionary movement.

“I believe Sun wishes everyone would listen to him. This is impossible, as his experience shows it would be risky to rely solely on him,” he wrote.

The Qing court ordered the assassination of Yeung at his home at 52 Gage Street in 1901. Meanwhile, the rift between Tse and Sun never fully healed, and when Sun later founded another revolutionary society, Tung Meng Wui, Tse declined to join.

However, the revolution was always on Tse’s mind. In 1931, he converted a two-storey building in Tsuen Wan into a museum to commemorate the Chinese revolution.

Elizabeth Sinn, honorary professor of the Hong Kong Institute for the Humanities and Social Sciences at the University of Hong Kong, said Tse’s colourful life could be used to illuminate many aspects of the political, social, economic and intellectual development of the city and modern China.

“His relevance to Hong Kong went beyond the Chinese revolution or the Post. Tse had an interesting mind and to some extent, reflected the intellectual transformations in Hong Kong in a subtler and more pervasive way than Sun Yat-sen,” Sinn said.

As comprador of the Post, Tse’s experience in the business sector injected innovation and creativity into the operation of the fledgling newspaper in its early years. In 1904, the Post was granted approval by the Works Department to install a wheeled news stand – the first mobile news stand in Hong Kong – outside the Peak Tram terminus on Garden Road. The newspaper paid a licence fee of HK$1 per

quarter.

Tse’s relevance to Hong Kong went beyond the Chinese revolution or the Post

It is unclear whose idea it was to set up the news stand. Chong Yuk-sik, author of a book on the history of news stands in Hong Kong, believed the idea might have come from Tse, who was employed by the department for 10 years.

“He was a man of imagination and vigour,” said Chong, also a research associate of the Chinese University’s Hong Kong Institute of Asia-Pacific Studies.

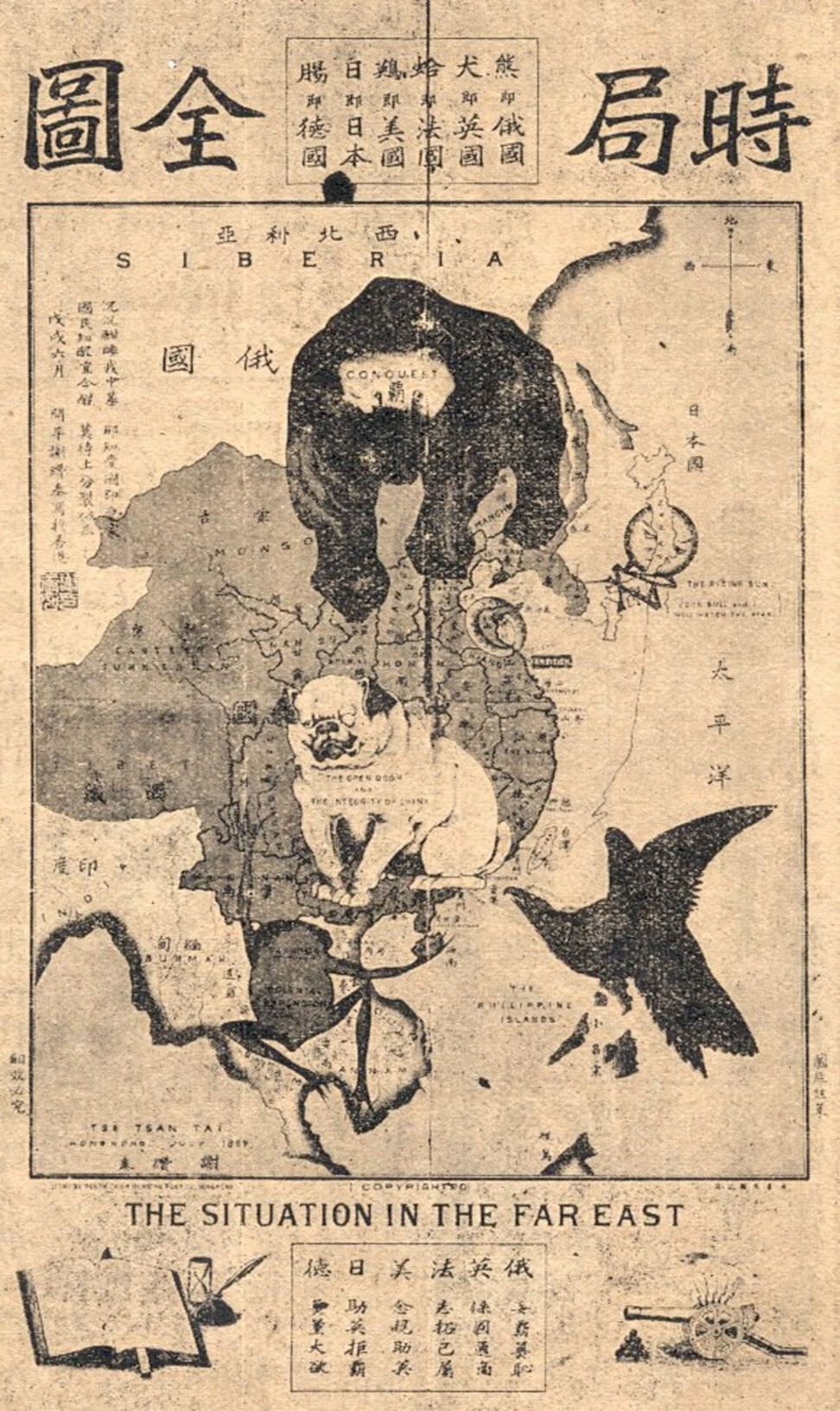

In 1899, Tse produced a drawing, The Situation in the Far East, widely regarded as the first political cartoon by a Chinese national.

It portrayed the scramble of the great powers (Britain, France, Germany and Russia) for influence in China in the late 19th century. The cartoon led to questioning of Tse by top officials of the colonial government. But it was widely circulated on the mainland in the 1920s, and has been cited in history textbooks in Hong Kong.

Tse also designed an airship, China, the plans for which were reprinted in several prominent illustrated journals of the day. His enthusiasm for technology also led him to getting involved with various railway and mining enterprises throughout his life, including mining petroleum, coal, limestone, marble and precious stones.

Hailed and assailed: reactions to the March 1925 death of Sun Yat-sen

He advocated the formation of a society for the suppression of foot binding in China, and called for abolishing old “evil practices” in the country, such as slavery, feng shui and opium smoking.

Advocating religious tolerance, he suggested establishing an Independent Christian Church for China. He also advocated forming an International Society for the Protection of Ancient Historical Relics. In January 1912, Tse telegraphed Sun, then president of the new republic, urging him “to prevent the auction sale of ancient Chinese treasures of the Peking and Fengtien palaces”.

Tse also weighed in on the political development in Hong Kong, and, in 1902, pushed for popular representation for Chinese in Hong Kong, insisting the Chinese representatives sitting in the Legislative Council should be elected by the people, instead of being nominated by the governor.

“It is a fact, and a glaring one,” he wrote, “that the past and present representatives of the Chinese have been more or less government automatons. How could it be otherwise, seeing that they were nominated and appointed by the government?”

Tse’s acquaintances amounted to a historical Who’s Who of contemporary China and Hong Kong. During a meeting in Hong Kong in 1896, Tse discussed with Kang You-wei – an intellectual who proposed that the country follow the constitutional models of Japan and Britain – the possibility of joining forces to promote reform in China.

Kang inspired the young Guangxu Emperor of the Qing dynasty to adopt many of his ideas during the Hundred Days’ Reform in 1898. But the short-lived reform was aborted after the Empress Dowager Cixi put the emperor under house arrest.

Tse spoke highly of Kang, describing the latter as “a man of superior intelligence” and “the most learned progressive Chinese scholar of modern China”.

Tse was a close friend of George Morrison, The Times correspondent in Beijing from 1897 until 1912, and a supporter of the 1911 revolution led by Sun. In 1912, Morrison became a political adviser to Yuan Shikai, then president of the Republic of China.

In 1898, Tse founded the Chinese Club, the Chinese business community’s answer to their exclusion from existing clubs by whites. Among the celebrities who joined the club were Ho Kai, a barrister and the first Chinese to become an executive councillor, and Robert Ho Tung, chief comprador of Jardine Matheson.

Tse died, aged 66, in 1938, and was buried in the Chinese Christian Cemetery in Pok Fu Lam.