Botched Botox, fatal blunders: is it time to rein in Hong Kong’s medical beauty industry? Complaints mount over loose rules, ‘unprotected’ clients

- Specialists urge tighter rules to cut down on unregistered drugs and procedures performed by unlicensed practitioners, with clients left nursing scars and irreversible damage

- Recent case of 19 people falling ill after fat-reduction jabs puts largely unregulated industry in spotlight again

Hongkonger Mary Lai* spent HK$45,000 (US$5,755) on beauty treatments that included injections of fillers under her eyes and a no-surgery facelift procedure.

That was three years ago. She was happy enough with the results until May this year, when hard lumps began appearing on her cheeks.

Her cheeks became unequal size, the left side visibly more swollen.

The 40-year-old fashion retailer went back to the well-known medical beauty chain where she had the injections, but it denied responsibility and prescribed her steroids.

2 arrested over unlicensed medical practices at Hong Kong beauty services chain

Lai turned to several specialists before a plastic surgeon finally told her to just “live with the lumps” because surgery to remove them could leave her face scarred.

“It took me months before I could accept it and tell others about my ordeal,” said Lai, who wore a face mask for months afterwards and needed counselling.

In all, she spent more than HK$60,000 for the checks, consultations and therapy sessions.

Hong Kong’s largely unregulated medical beauty industry was in the spotlight again recently, after 19 people fell ill with a bacterial infection after receiving fat removal injections at a chain in Lai Chi Kok.

Four people were arrested in early November on suspicion of carrying out unlicensed medical practices.

In a separate case in late-November, two women at another medical beauty parlour in Mong Kok were arrested for the same alleged offence.

They allegedly administered injections, including wrinkle-smoothing Botox jabs, to more than 700 customers over the past year, and prescribed steroids to minimise side effects.

Industry players, doctors and others who called for a more comprehensive framework to monitor and regulate the medical beauty sector conceded that enforcing tighter controls would be challenging.

They agreed that public awareness needed to be raised urgently about ways to stay safe when seeking such beauty treatments.

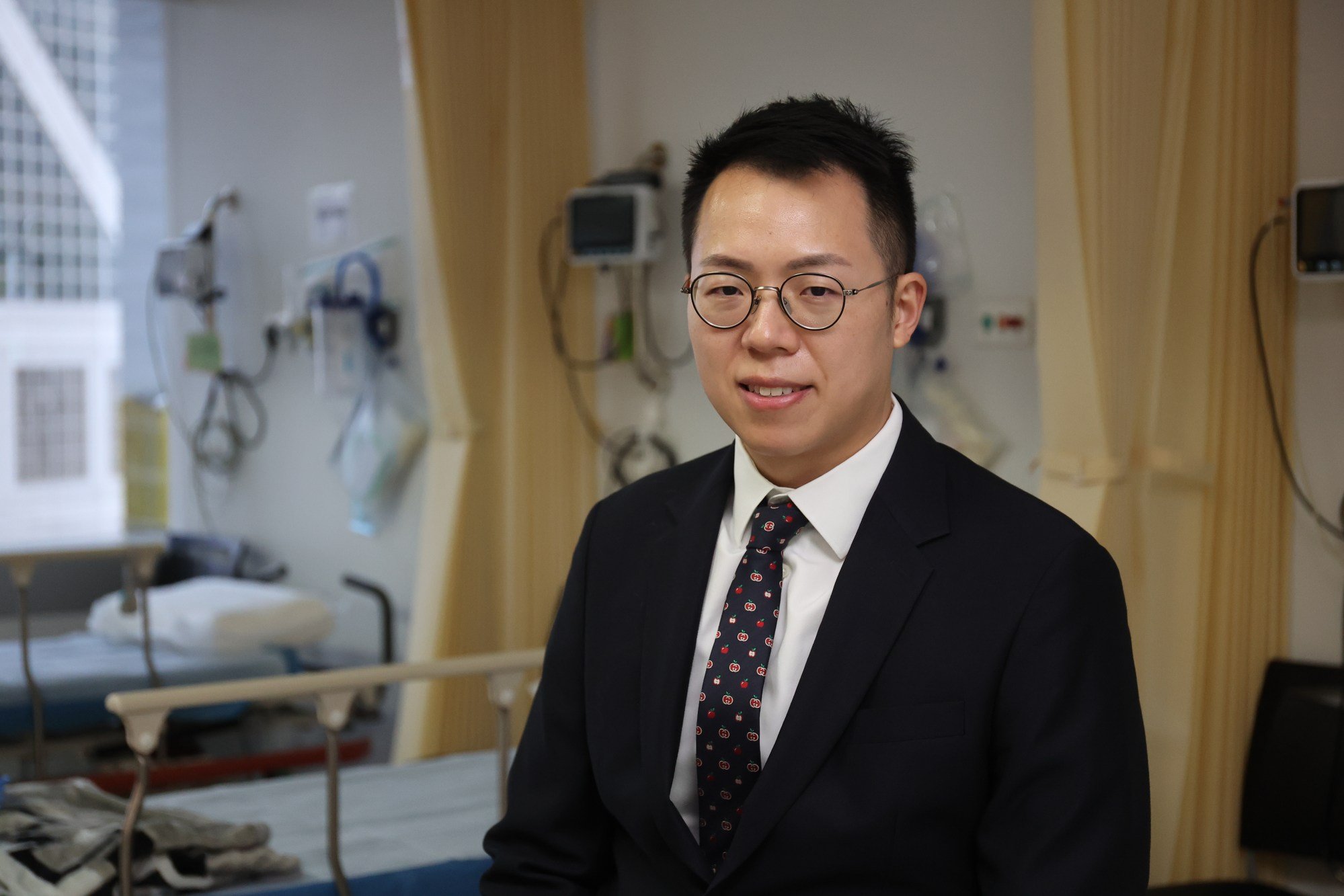

Dr Gregory Lau Siu-kee, the plastic surgeon who advised Lai to live with her botched beauty treatment, said her case was just the tip of the iceberg.

He said he saw about a dozen patients every year with a variety of unwanted outcomes to medical beauty procedures.

“It’s very difficult to regulate the medical beauty industry,” he said. “Who is in the position to draw the line?”

It meant making sure that medical aesthetic products on the market were of good quality, from credible sources and would be used properly, and those offering such services underwent training to be competent.

For example, Botox injections have been approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration for specific treatments, but are often used by doctors for other aesthetic purposes.

In Lai’s case, the reasons for her abnormal condition remained unknown as she did not know what product was used, the quality or source.

Lau said it was not easy to set clear standards for those in the industry because “they are not treating a disease”.

No governing legislation or definition

Hong Kong has no specific laws for medical beauty services. There is no official definition of the term, though it is commonly understood to mean aesthetic treatments to improve clients’ physical appearance.

These include procedures to smoothen wrinkles, reduce excess fat and remove unwanted hair.

The city has about 6,000 beauty parlours, but it is not clear how many provide medical beauty services.

Specific rules govern the premises, equipment, drugs, sales practices and professional conduct of medical practitioners, mostly introduced after botched treatments resulted in a number of deaths in the past decade.

There has been no end to complaints from unhappy clients.

The Consumer Council has issued repeated warnings about potential traps in medical beauty services, after receiving hundreds of complaints about quality and sales practices.

In the first nine months of this year, it received 202 complaints, mostly related to laser or intense pulsed light treatments, followed by invasive treatments.

In 2016, the watchdog urged authorities to define “medical beauty” and tighten controls, so that there would be a legal basis to regulate the industry, with a clear licensing framework, specific operating codes and competency requirements for practitioners.

Little was done, and cases of botched treatments and unhappy clients have continued to surface.

Plastic surgeon Dr Peter Pang Chi-wang said: “The term ‘medical beauty’ gives a sense of security, making people think the procedures they undergo are of a medical standard – professional, clean and safe. But are they?”

He has treated patients unhappy with the results of medical beauty procedures done in the city and also places such as South Korea, Taiwan and Thailand.

Pang said their frustrations often stemmed from mismanaged expectations, as they were not made aware of potential side effects, including some temporary conditions which would subside.

More serious problems arose from the use of unregistered drugs, the wrong dosage or, in the worst cases, unlicensed practice by individuals who were not doctors and performed procedures in beauty parlours, hotel rooms, at home or even in public toilets.

Some of those cases were challenging to treat and some patients were left with irreversible damage.

“The landscape of the industry has changed a lot,” Pang said. “Some progress was made in the past decade by the government following the fatal blunders … with efforts mainly on regulating doctors.”

More than a medical license needed

In 2013, health authorities listed four procedures – injections, mechanical or chemical exfoliation of the skin below the epidermis, hyperbaric oxygen therapy and dental bleaching – as requiring administration by registered doctors or dentists.

There are about 400 doctors providing aesthetic treatments, mostly general practitioners and the rest being specialists such as dermatologists and plastic surgeons.

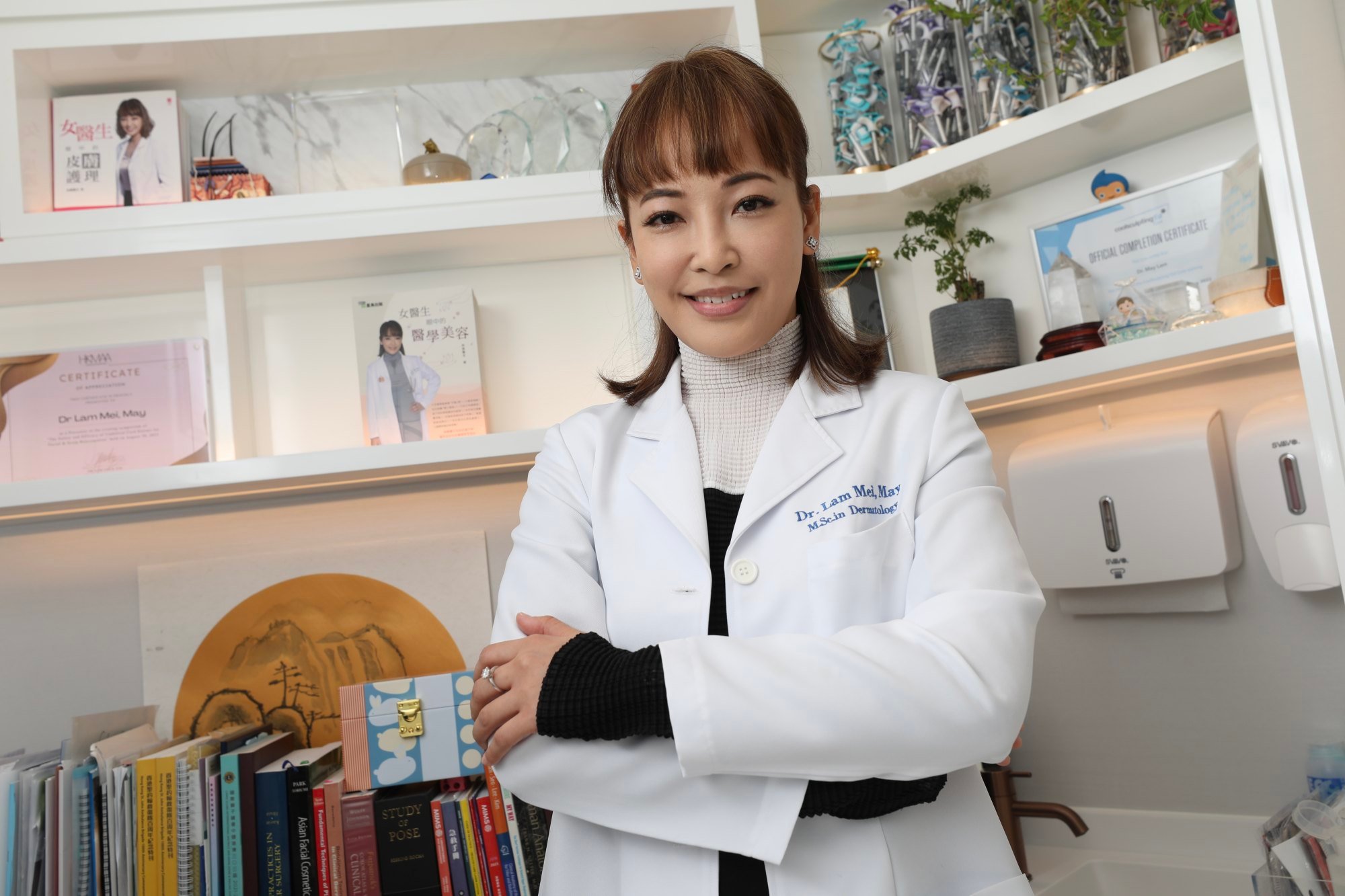

General practitioner Dr May Lam Mei, who has a special interest in aesthetic medicine, said it was not recognised as a medical specialty.

So doctors had to seek training on their own in Hong Kong or overseas, some of which was recognised by the Medical Council, including certain diplomas or master’s degrees in clinical dermatology, but no aesthetic medicine qualifications were regarded as “quotable qualifications”.

Organisations, including the manufacturers of medical devices and aesthetic products, also offered on-the-job training, fellowships, workshops and academic seminars.

“Training opportunities are abundant but not structured,” the general practitioner said. “There are no requirements for examinations, clinical training or research papers, because aesthetic medicine is not a specialty.”

Plastic surgeon Dr Stephanie Lam Chuk-kwan, founding president of the Hong Kong Medical Aesthetic Association, said the city needed a more comprehensive training framework in the long run.

Many qualifications were not officially recognised and the training quality was not guaranteed, she said, and many doctors were not fully engaged in the industry but worked at beauty parlours on weekends as part-timers.

But the plastic surgeon noted that a number of medical beauty blunders were the result of people practising without a licence, with injections done in non-clinical settings by non-doctors.

Police arrest 2 after 15 Hongkongers develop infection from fat removal injections

The more urgent task, she said, was to step up public education to ensure residents were aware that invasive treatments should always be done by registered doctors using devices from authorised distributors or manufacturers.

She said people did not even know how to verify the authenticity of products used for such procedures. For example, some had a scratch-off QR code which linked to a webpage showing the origin of the product.

“The doctor should open the box in front of the clients, and show them it’s the genuine product.” she said.

It would be better if the products had to be registered in the city, she added.

Medical devices unregulated

Vam Cheng, chief executive officer of Good Union Corporation, which supplies a third of all medical aesthetic devices used in the city, said parallel-imported products had plagued the industry, putting clients’ safety at risk.

Products listed with the health authorities had to follow protocols on delivery, distribution, storage and recall, none of which applied to parallel imports.

“Without regulations, customers often bear sole responsibility when blunders happen,” he said.

There is no specific legislation regulating the manufacture, import, export and sale of medical devices in the city.

Manufacturers and importers can list their medical devices with authorities voluntarily, and be subject to a set of protocols, including having to report adverse events.

In 2017, the government submitted a proposal to regulate the use of medical devices, including some involved in cosmetic treatments, but the bill did not go before the Legislative Council.

It proposed that all devices had to be registered before they could be put on the market, except those with the lowest risk, such as bandages.

It also included trader registration and licensing, post-market surveillance and an adverse incident reporting system. The operator of the devices would not be subject to any restrictions.

The government told lawmakers on Wednesday that rules governing the devices would fall under the Hong Kong Centre for Medical Products Regulation, and a preparatory office for the centre would be established next year. The centre was first revealed in the policy address in October to develop the city’s own approval system for drug registration.

In response to suggestions for regulating certain procedures in the beauty industry, authorities said such measures would not effectively prevent similar incidents from occurring again. They expressed concerns that such regulations might create a misconception among the public that the industry was permitted to perform medical procedures.

“The government will consider the legislative timetable for regulating medical devices in tandem with the progress of establishing the [centre], thereby further enhancing the overall regulatory regime for medical products in Hong Kong,” Secretary for Health Lo Chung-mau said.

The Health Bureau and Department of Health are also reviewing the proposed legislative framework for medical devices, and studying the regulation of high-risk products.

Marketing approvals from Australia, Canada, Japan, the United States, European Union, South Korea and mainland China would be accepted as documentary evidence for registration.

Devices falling short of the requirements could be subject to a five-year transitional arrangement, including those for household use.

Good Union’s Cheng said he would welcome regulations on medical devices used for aesthetic treatments to weed out questionable parallel imports, and called for tighter control on bringing in such products.

A registration and listing system had to enable tracing and tracking of devices so that if quality issues arose, the authorities could recall products easily.

He said the government should also require doctors to operate devices deemed high-risk, including those that could result in permanent damage or life-threatening conditions.

He suggested that the government form a committee made up of experts including doctors, beauticians, technicians and suppliers, to keep up with the latest developments in medical aesthetic technology and advise on relevant policies.

Medical sector lawmaker David Lam Tzit-yuen said the government must define “medical procedures” clearly to provide a legal basis for rules.

“Some high-energy devices could burn one’s skin if used inappropriately,” he said. “That should be regarded as a medical procedure but it is offered as a beauty treatment. Without a definition, how can we regulate that?”

Hongkongers freshen up with lipstick, spa days after axing Covid mask mandate

Licensing regime due to be in place

Updated rules concerning the premises where medical beauty procedures may be performed are also in the pipeline.

In 2018, the government enacted the Private Healthcare Facilities Ordinance, requiring beauty parlours performing medical procedures to get a day care centre or clinic licence from the Department of Health.

But applications for clinic licences have not yet opened. The department said it was still in the process of establishing standards for regulating clinics, drafting relevant codes of practice and coordinating staffing arrangements.

It said it would stay in close communication with the industry.

The Democratic Party’s Ramon Yuen Hoi-man, convenor of the Hong Kong Beauty Industry Monitor concern group, said the progress of licensing clinics had been too slow.

Hong Kong doctor among 4 arrested over botched Botox injections

“With a licensing regime, people can immediately tell which ones are clinics and which are not,” he said. “It will also be easier for the government to crack down on unlicensed practices.”

A licensing regime would also offer stronger protection for consumers, as it would hold a clinic’s chief medical executive, a registered doctor, accountable.

“That way, when blunders happen, consumers can easily trace the licensees,” he said.

Nelson Ip Sai-hung, founding chairman of the Federation of Beauty Industry (HK), said the government should not treat their premises as healthcare facilities.

Instead, the industry needed its own statutory regulatory mechanism, with a licensing regime tailored for service providers.

“It’s time for the government to face the reality and acknowledge the existence of medical beauty services,” he said.

“Our clients are not patients, our services are not entirely medical, and that’s not how we run the business as well.”

Part-time saleswoman Shirley Chan*, 23, had Botox injections last December to slim her jawline after seeing an advertisement on Instagram.

“It was not done at a clinic, but just a tiny unit at a commercial building, and the reception and injection area were separated by a huge board,” she recalled. “I was slightly worried, but I thought it should be fine, and I already paid the HK$500 deposit.”

Two days later, a bump appeared on her right jaw, leaving her face asymmetrical. To fix it, she had another jab at the same parlour a month later, but it did not help.

“I only learnt that the amount of Botox used was exceptionally high after I joined a Facebook group to seek the advice of others,” she said. “The parlour kept denying responsibility and subsequently blocked me on Instagram.”

Chan said she did not know where to file a complaint. Instead, she avoided meeting people as she waited six months for the effects of the jabs to wear off and the bump to disappear.

Swearing never to undergo such treatments in Hong Kong again, she said: “The parlour is still operating. As customers, we are so unprotected.”

*Names changed at interviewees’ request

Additional reporting by Elizabeth Cheung