From Hong Kong hit Bride Wannabes to the Kardashians and Love Island, what is our fascination with reality TV?

From its early beginnings with Candid Camera in the late 40s, the genre began its current boom around the turn of the century with competitive shows such as American Idol and Big Brother

Reality television is like durian – most people seem to either love it or hate it. But the genre has proved long-lasting, popular and often controversial.

Five years ago, a 10-episode series Bride Wannabes hit Hong Kong’s TV screens. It featured five single women in their 30s being coached for six months on how to attract Mr Right and drew 1.7 million viewers every night – almost 25 per cent of the city’s population.

But the show also drew huge criticism, for giving narrow and distorted definitions of beauty and success for women. A Facebook page “Say no to Bride Wannabes” gained 2,300 likes in one week.

A more recent local reality show was Nowhere Girls in 2014, centred around seven women who were described as lacking money, jobs, education and prospects. It received 76 complaints in five days.

“In Hong Kong, the media content and digital programmes produced are not only competing [locally], but also against shows from other parts of the world – the United States, China, and South Korea in particular,” said Dr Tommy Tse, assistant professor of sociology at the University of Hong Kong.

Most younger people are attracted to international content made using larger budgets, Tse added.

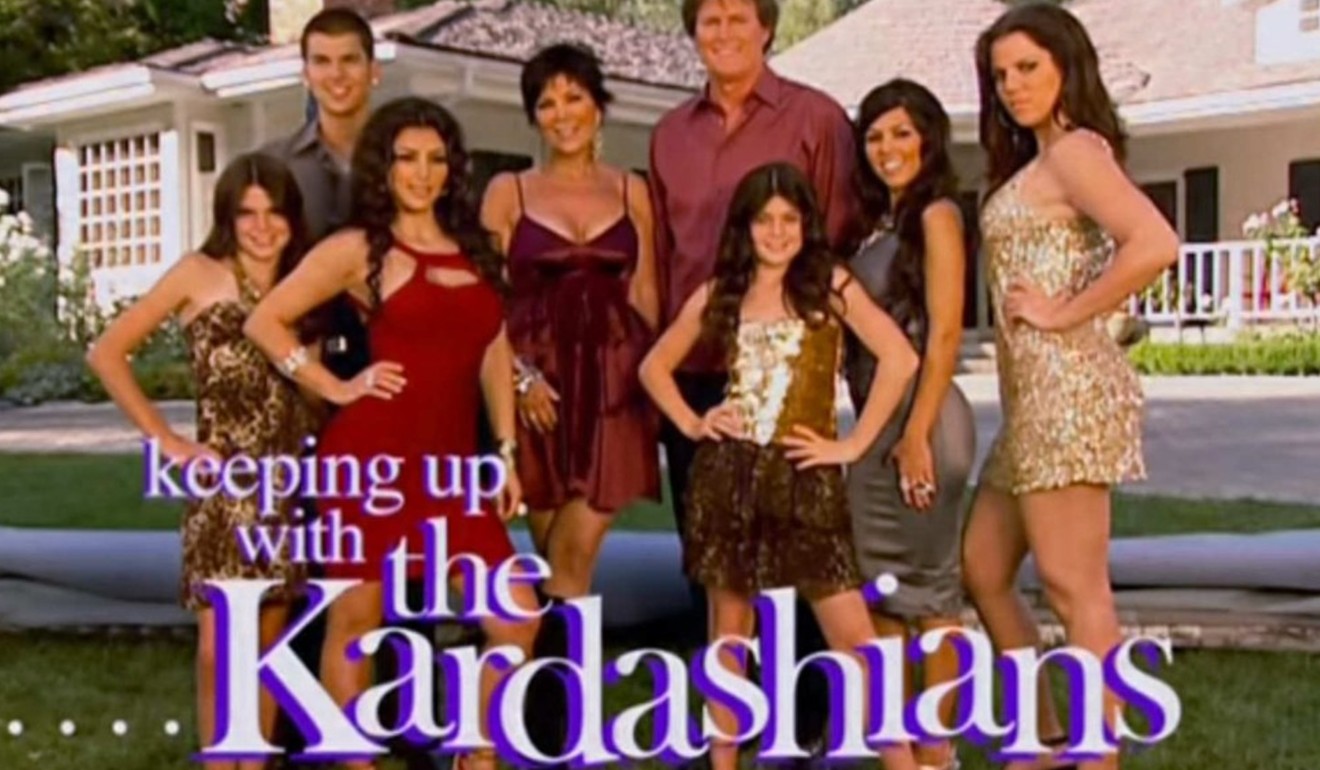

This month marks the 10th anniversary of Keeping Up With The Kardashians (KUWTK), an American reality show following the lives of the Kardashian clan: mother Kris, daughters Kim, Khloe, Kourtney, Kendall and Kylie, and other family members.

A 90-minute special, with the family who has a net worth of US$450 million reflecting on the past decade, marked the occasion and began their 14th season in front of the camera. A decade that reached millions worldwide – 10.5 million for the most watched episode – tuning in each week to watch strangers’ lives.

Rated the most popular reality TV series by the Internet Movie Database, KUWTK is by no means a new concept.

The first reality TV was American practical joke show Candid Camera in 1948, which ran until 2014, and was also aired in Hong Kong for a few years. In the show, ordinary people were filmed by hidden cameras in unusual situations.

The genre then exploded in the late 1990s and early 2000s with the global success of competitive reality series, such as singing contest American Idol and the UK’s Big Brother – in which contestants were filmed living in a house being pitted against one another, while viewers at home voted for their least favourite to be evicted.

In more recent shows, including KUWTK, “ordinary” people’s supposedly uncontrived lives are filmed as entertainment, ultimately for their own benefit. Some use it to become famous, like The Kardashians; some to boost their career, like One Direction who began on the UK’s X-Factor, and some gain publicity which helps them further down the line, like now-President Donald Trump who hosted The Apprentice in the United States for 14 seasons.

One of China’s most popular shows Where Are We Going, Dad? features five celebrity fathers and their children as they travel to rural places, based on a South Korean series.

South Korean shows are popular with young Chinese people as they prefer “programmes that involve more real, unscripted elements than those which still rely heavily on scripts”, said 23-year-old Milly Zi who lives in Beijing.

She watches them for humour and education. Using Chinese subtitles, Milly learns about activities she would not otherwise come across, such as watching someone become an elephant tamer for the day in Korea’s most popular reality show, Infinite Challenge.

Tse argued that, culturally speaking, South Korea offers a cultural proximity to Chinese viewers.

“Some of them can really resonate with the ideas, the content and the social and cultural values that are being presented in those show”, he said.

“The best series always have really relatable people who are still a bit out there and make you laugh”, said Sarah James, 22, a confessed addict to British reality dating show Love Island.

“You feel like you could know them and so get really absorbed in their lives because you have real opinions on what they’re doing.

“It’s just so entertaining to see a world you’d never see otherwise and laugh at how ridiculous the people and the situations are. The actual premise or structure of the show really doesn’t matter much.”

But for 26-year-old Georgie Barber, who lives in Hong Kong, the “mindless” premise of the show is exactly what makes it a “complete waste of time”, catering to those who don’t want to think after a long day at work.

So what do experts say about why we love, or love to hate, reality television?

Feelings towards celebrities

“We have mixed feelings towards celebrities – we worship them as a far-from-Earth, perfect-being and yet we also want to be close with them like our friends,” said Tse. “Sometimes we identify with them on a fantastical level, as we want to have a chance to become famous overnight like the stars and reality shows satisfy us in this way”. This, he said, is a global phenomenon.

Empathy

A 2016 study, “Why Do We Enjoy Reality Shows: Is it Really All About Humiliation and Gloating?” found empathy for contestants, not their humiliation, was the motivation for watching the shows. It was led by Michal Herschman Shitrit and Jonathan Cohen from the University of Haifa in Israel and surveyed 183 viewers about 12 reality shows.

Superiority

A study in 2003, “Reality-based Television Programming and the Psychology of Its Appeal”, found the downward social comparison towards those on the shows made the viewer feel superior, promoting self-reflection. It aimed to understand why people gravitate towards reality TV and what they get out of it, led by Robin L Nabi from the University of California, Santa Barbara.

Status

The main motivation for watching reality TV, according to 2001 study “Why People Watch Reality TV”, was status: ordinary people watch the shows, see people like themselves and imagine they too could become celebrities by being on television.

Graphics: Emilio Rivera