Discover defining Hong Kong architecture, from the ultra-modern to colonial relics

Hong Kong is a city torn between East and West, the future and the past, as reflected in its notable architecture

Wander around Hong Kong and you will see “Taoist temples and Edwardian edifices nestled between skyscrapers”, the city’s Tourism Board says.

Hong Kong is filled with both the old and the new, but for years, poor preservation of the former has been a worry for the local community.

From the Old Hong Kong Club Building to Queen’s Pier, structures of the past have been demolished to make way for modern glass offices and residential tower blocks.

“We have a whole range of buildings which practically tell people about the whole development of architecture in the city’s history,” says Dr Lee Ho-yin, associate professor of architectural conservation at the University of Hong Kong.

The older buildings, of different heights, create a more varied picture, rather than buildings that are “taller, denser and more expensive”, he says.

“By tearing them down we are really undermining ourselves ... by not having an environment that is diversified to make it more interesting and sustainable.”

Keeping older buildings intact however has served up the problem of what to do with them.

Some are preserved and declared historic monuments, of which there are 117 in the city. They receive the highest level of protection under the law. This week three more were added – two temples and a church.

Inside Fujian’s Unesco-listed Hakka roundhouses: their history, architecture and why heritage status is mixed blessing

Another 1,444 buildings have been graded as historic buildings subject to a less strict form of protection.

But rather than sparing such buildings from the wrecking ball just to turn them into museums or pieces of history to be stared at, practical ways to reuse them should be found.

With space being such a vital commodity in Hong Kong, reusing buildings is both efficient and maintains the city’s diverse character, Lee says. There has been some movement towards this.

In 2007 Hong Kong launched the Heritage Conservation Policy to protect and repurpose historic buildings. It is part of what Lee calls “sustainable conservation” – refurbishing existing buildings to embrace the past and recognise the city’s cultural identity.

From restaurants to architecture: how Hongkongers are forgetting their modern-day woes by bringing back the good old days

Chris Patten, the last colonial governor of Hong Kong before the city’s return to Chinese sovereignty in 1997, said: “No other place has quite the same blend of East and West, ancient and modern, spectacular and humdrum.”

City Weekend has chosen a few old favourites around Hong Kong to illustrate Patten’s point.

Murray House

Dismantled brick by brick in Central and reassembled in Stanley in 2001, this classic colonial building was first built in 1855 as an officers’ quarters for the British army. It now sits on Stanley’s southside waterfront, filled with restaurants and shops.

Man Mo Temple

Built in 1847 on Hollywood Road in Central, this is the largest Man Mo temple in Hong Kong. Man is the god of literature and Mo the god of war in Chinese mythology. Originally used as a place of worship for students wanting to do well in the civil examinations of imperial China, it is now preserved as a declared monument and grade one historic building.

Antiquities and Monuments Office

Opened in 1902 as the Kowloon British School on Nathan Road, this is the oldest surviving school building constructed for Hong Kong’s expatriate community, and is a declared monument.

Its architecture is typical of the British Victorian era, with some adaptations to cope with the local climate including wide verandas, high ceilings and pitched roofs.

Blue House

A four-storey house built in the 1920s with a mixture of Chinese and Western architectural features, it is painted this colour because decorators only had blue paint.

Located in Wan Chai, it is a grade one historic building and one of the few remaining examples of a tong lau: a style of residential building notable for balconies that was built in the late 19th century in Hong Kong, Macau, southern China and Taiwan.

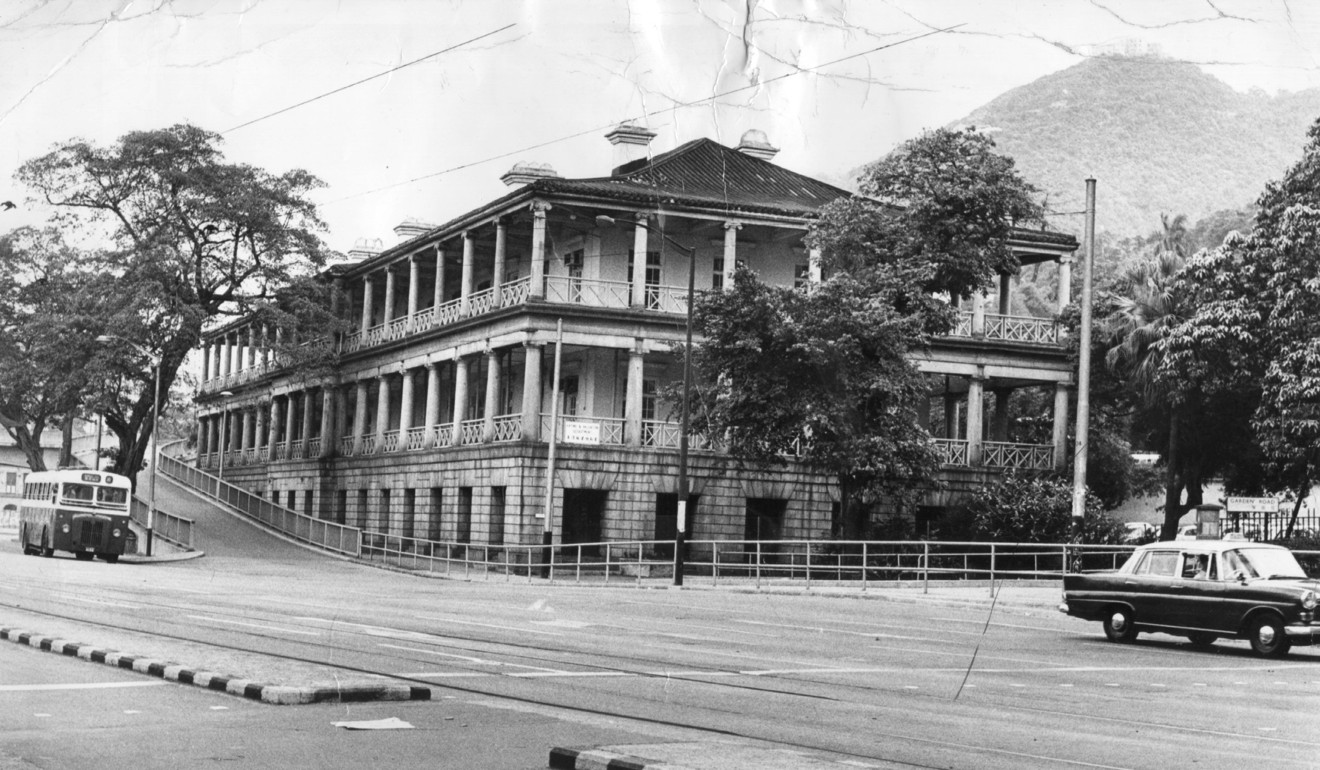

Government House

Sitting in the Mid-Levels above the city is the former official residence of 25 British governors until the 1997 handover.

The home was built in 1855 in colonial Georgian style, before the Japanese, who occupied Hong Kong during the second world war, redesigned it to add a tower and roof elements.

It is now home to Hong Kong’s current leader, Chief Executive Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor.

The city’s first rural medical clinic sits in Sheung Shui in the New Territories, and is a mixed style of Chinese and Western architecture. Constructed in 1933, it was originally a maternity centre, before becoming a hospital for Indian soldiers, and then a general outpatient clinic. The centre is a grade two listed building.

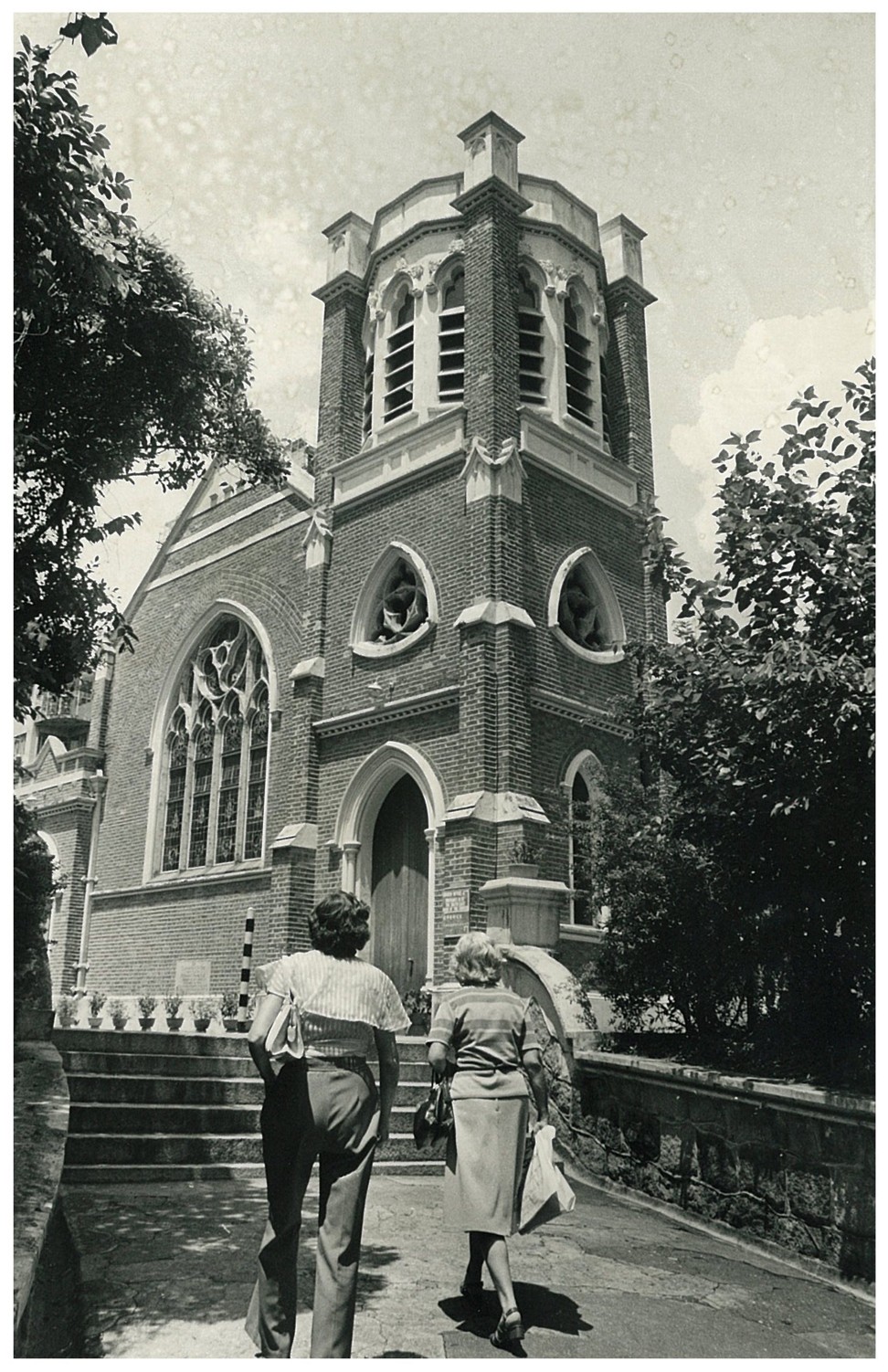

St Andrew’s Church, Kowloon

St Andrew’s on Nathan Road is the oldest English-speaking Anglican church in Kowloon, after opening in 1906.

It was built for the Anglican community who used to congregate about 600 metres away at a torpedo depot, where a navy chaplain led services. During the second world war the church was used by Japanese forces as a shrine for the Shinto religion.

It is constructed in a Victorian Gothic style using red brick with granite detailing, and still houses its original bells and stained glass windows, which were both made in England.

Lui Seng Chun

Located in Mong Kok, this four-storey tong lau built in 1941 is a grade one historic building.

As part of the government’s plan to reuse such buildings, it was revitalised in early 2012 and is now used by the Hong Kong Baptist University as a Chinese medicine and health care centre.