Explainer: how Hong Kong has for decades been a magnet for refugees and migrants

The city has long attracted those fleeing persecution as well as many in search of a better life

Hong Kong has a rich history of immigration and has long been a destination for refugees. This is deeply woven into the city’s multicultural heritage. The economic miracle of the 1960s and 70s was largely built on the back of cheap refugee labour that powered a manufacturing boom.

But refugees have also made local news in more recent times. In 2013, US National Security Agency whistle-blower Edward Snowden found shelter in the homes of asylum seekers from Sri Lanka and the Philippines for two weeks as American authorities launched a worldwide manhunt for the fugitive behind one of the biggest data leaks in history.

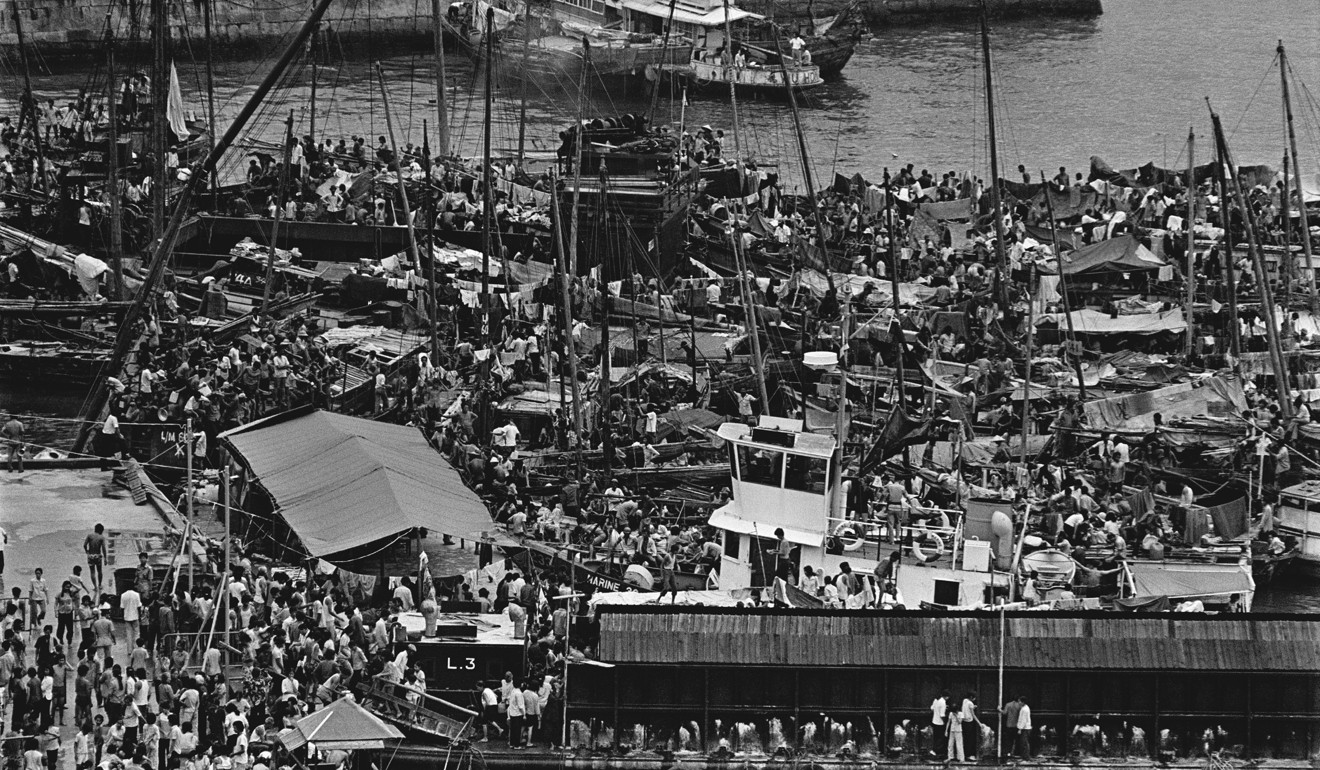

The first wave of mass immigration to Hong Kong in the modern era saw the population explode from 600,000 to 2.1 million between 1945 and 1951, as mainland Chinese rushed to flee the horrors of the country’s civil war and communist revolution that followed.

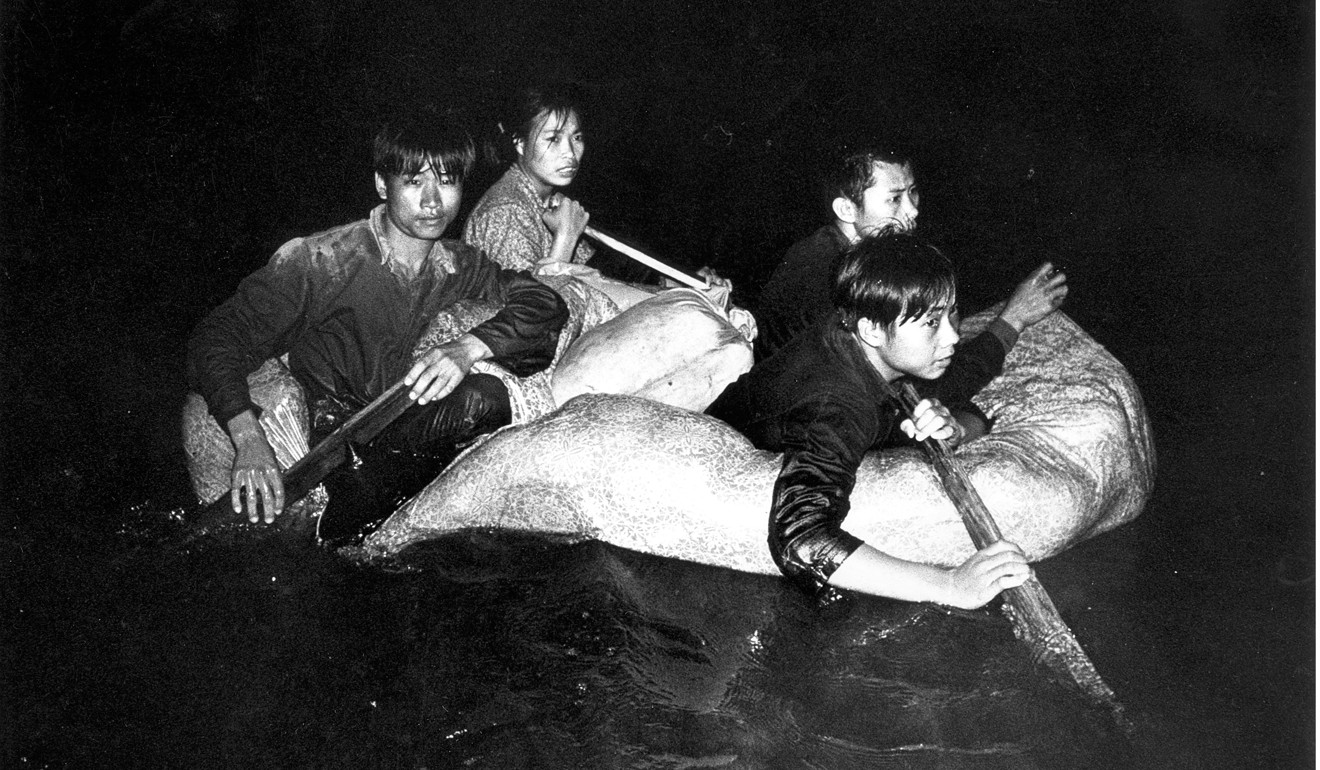

As many as 100,000 came to the city each month after the Communist Party took power in 1949. Many secretly swam the perilous 4km stretch of water from Shenzhen, risking death by drowning or being shot by People’s Liberation Army guards.

Hong Kong’s population count continued to rise exponentially in the years that followed, reaching 3.1 million by 1960 and just under 4 million by 1970. Today, the city’s population density is one of the highest in the world.

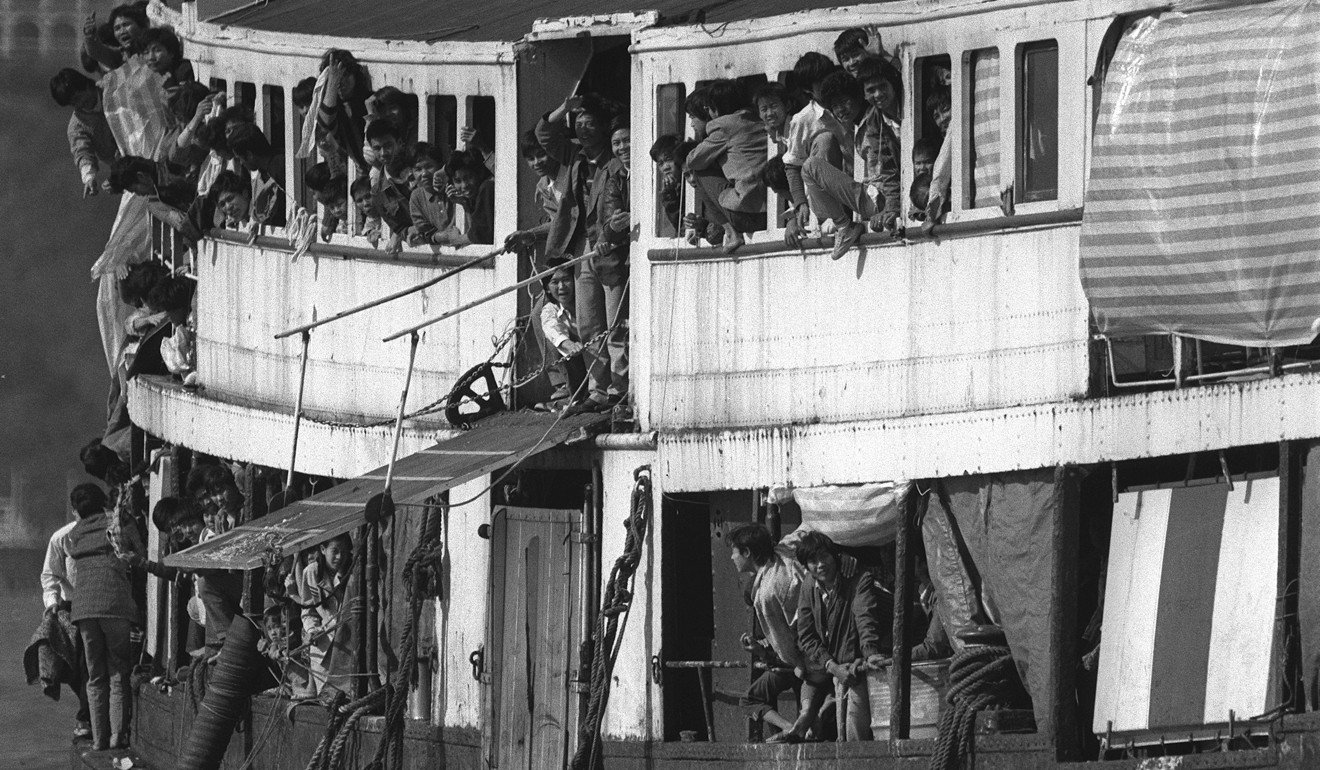

The Vietnam war brought more than 200,000 refugees by boat in the mid-1970s. They languished in appalling conditions in purpose-built detention centres. Only about 1,400 were allowed to stay in the city permanently. By 2000 some 143,700 had been forcibly resettled to other countries and 67,000 sent back to Vietnam.

Global warming to boost poverty and drive more ‘climate refugees’ to Europe, says study

Hong Kong’s immigration policies had been relatively lenient up until 1988, when it introduced a new screening system. The city is now unique among wealthy, developed jurisdictions in that it has refused to sign up to the 1951 United Nations Refugee Convention, which safeguards the rights of refugees.

So what kind of people make the often dangerous journey to Hong Kong in search of a better life? Those who come are generally placed in one of four categories:

Economic migrants

An economic migrant is someone who leaves the country where he or she was born in search of better living conditions. Different to refugees, economic migrants are not forced to leave their countries due to a fear of persecution.

The number of foreign nationals (which excludes arrivals from mainland China) living in Hong Kong climbed 41 per cent in a decade to reach more than 568,000 by last year, making up 7.7 per cent of the population, according to the government’s Census and Statistics Department.

Nine Hong Kong chefs turn up kitchen heat for Syrian refugees

Foreign domestic workers are the largest group of economic migrants. Mostly from the Philippines and Indonesia, the 352,000 helpers in the city account for 9 per cent of the workforce and serve 11 per cent of Hong Kong families, according to the Legislative Council Secretariat.

Mainland Chinese are the third biggest migrant group, with their numbers up 41 per cent between 2006 and last year. There are about 121,000 living in Hong Kong. Former colonial rulers the British represent only 0.5 per cent of the population.

Refugees

According to the 1951 UN convention, a refugee is a person who flees their country of origin and cannot return due to a fear of being persecuted for their race, religion, nationality, social group or political opinion.

According to Justice Centre, a local NGO that provides legal assistance to refugees, Hong Kong has one of the smallest global refugee populations, at less than 1 per cent of the population.

The current refugee acceptance rate is 0.6 per cent, falling well short of many European countries, where it can be as high as 75 per cent for certain nationalities.

Giving shelter: Hong Kong photo exhibition sheds light on rich history of refugees in the city

The Hong Kong government’s official stance is that it does not resettle refugees, but that has not stopped about 14,000 seeking asylum as of September this year. Many are from South Asian countries such as India, Pakistan and Bangladesh. A number arrived in the city after 2004, when Hong Kong courts ruled that illegal immigrants could not be deported by immigration police if they had applied for asylum due to torture.

So far, only 103 refugees have had their asylum claims accepted by Hong Kong authorities since 2009, according to Justice Centre policy officer Annie Li. In recent years pro-Beijing lawmakers have lobbied against so-called “fake refugees”, who they accuse of abusing the system.

Public opinion on refugees and asylum seekers is often negative in Hong Kong, which critics say is partly due to xenophobic rhetoric from the government on the issue.

World’s biggest refugee camps ranked: Bangladesh prepares to host 800,000 Rohingya as crisis deepens

“There are lots of public misconceptions about refugees in Hong Kong,” says Dr Terence Shum Chun-tat of the Technological and Higher Education Institute of Hong Kong. “Some politicians and Legco members have been using refugees as a strategy to buy votes from the public, portraying them in a negative light.”

Asylum seekers

An asylum seeker is someone who claims to be a refugee and is awaiting confirmation (or rejection) of their asylum status from the country they wish to settle in.

While asylum seekers wait for claims to be processed, which can take up to several years, the Hong Kong government provides them with just over HK$3,000 per month for housing, transport and food.

Exhibition captures how Hong Kong once opened its arms to refugees

As asylum seekers are not permitted to take up employment, many work illegally in the informal economy to earn beyond their meagre allowance in one of the most expensive cities in the world.

“They are not allowed to work, they have no right to education, and they have all sorts of challenges facing them every single day,” Shum says. “The government should hasten the screening process to reduce the psychological torture asylum seekers suffer.”

Li says the government should consider allowing asylum seekers to work so they can contribute positively to society.

“Hong Kong’s population is ageing,” she says. “The government is talking about importing people from other countries to work here, so why don’t they look at this group of people who are already here and really want to work and contribute?”

Eating like a Hong Kong refugee: teacher lives on HK$40 food a day for charity

Li also recommends the government look to policies in Europe for dealing with asylum seekers, as a possible model for helping them gain legal employment and integrate into society.

Illegal immigrants

An illegal or undocumented immigrant is someone who “enters a country, usually in search of employment, without the necessary documents and permits”, according to the UN.

The number of illegal immigrants in Hong Kong has declined significantly over the past two years as the police join efforts with mainland law enforcement agencies to crack down on cross-border human smuggling.

Fewer illegal immigrants arrested in Hong Kong after joint crackdown on people smugglers with mainland police

Hong Kong police arrested a total of 837 non-Chinese illegal immigrants between January and November this year, down 60 per cent on the same period last year. In 2015, more than 300 such immigrants were arrested each month on average.

Most were from South and Southeast Asian countries such as Pakistan, India, Bangladesh and Vietnam, and had come looking for work.

Illegal immigrants from the mainland have also decreased in number, by 41 per cent from the 783 in 2015, to 465 last year. Most came to take up jobs or be with family or relatives, according to the Immigration Department.