25 years on, Hong Kong’s Kowloon Walled City still evokes awe and revulsion

Former residents recall stories of crime in dirty alleys and dark mazes, but also a sense of community and nostalgia living among cramped quarters of the historical landmark

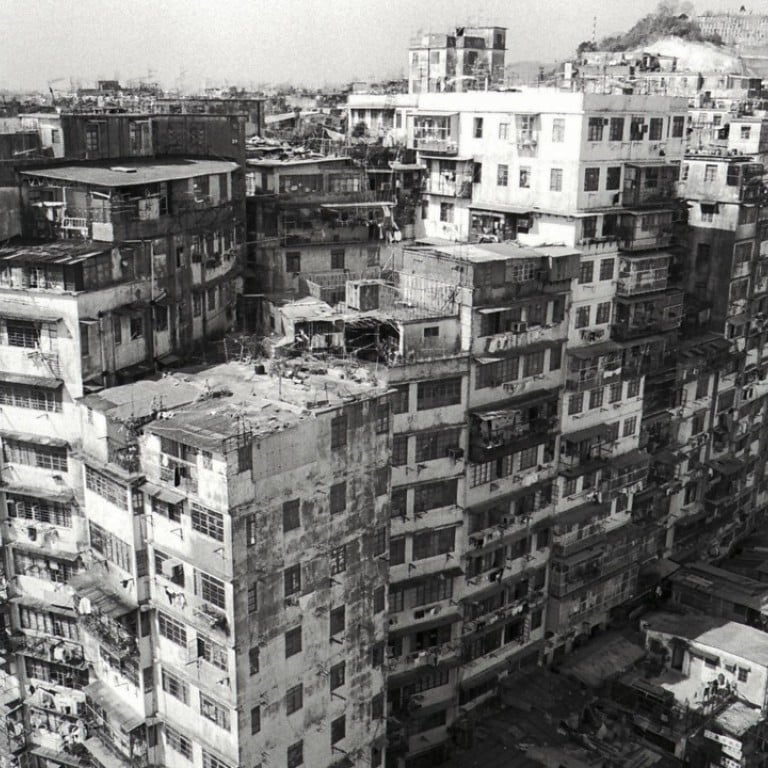

Twenty-five years ago this Friday, bulldozers moved in to tear down the Kowloon Walled City, a condemned slum area that now evokes fascination and revulsion in Hong Kong’s collective memory.

Urban myths have persisted over the reluctance of the pre-handover Royal Hong Kong Police to impose order in the lawless enclave, considered a remnant of the Qing dynasty (1644-1911), having been a military fort.

Today a park sits at the core of what was a 2.7-hectare (6.7 acres) mass of 350 slum buildings interconnected by ramshackle footbridges.

Dark legacy of Kowloon Walled City lives on in modern-day Hong Kong

Lau Chun-fat, 83, a former resident of the notorious settlement, was on a regular noon stroll in the area when the Post approached him in what is now the Kowloon Walled City Park. The retired toy factory worker said he felt “even safer” when he was living in the community.

“Those hooligans didn’t dare come in because it was not their neighbourhood,” he said.

Yet, for US-based doctor Vivian Chan, the Walled City is but a distant unwelcomed memory. The family physician, who is in her 40s, spent more than 10 years there during her childhood and adolescence.

“My neighbours would tell me a lot of their stories and anecdotes, about who was being beaten up, who was taking drugs and who was being sexually assaulted or raped.”

One Hongkonger recalled a derring-do with friends after the site was cleared and the buildings fenced off. They sneaked in through a gate that was not chained up properly, and explored the abandoned structures.

Most of the doors were opened, and some households still had furniture and personal belongings or photos inside, the man, who preferred to remain anonymous, said. “It was quite sad in a way, to see those memories left behind,” he told the Post.

Though the British claimed ownership of the Walled City from 1898, they did little with it over the next few decades.

After a failed attempt to gain control of the place in 1948, the British adopted a “hands off” policy, so triads and other illegal activities prospered. It was only after a murder in 1959 that the Hong Kong government was ruled to have jurisdiction there.

Eric Lockeyear, a retired chief superintendent who served in the police force from 1963 to 1996, starting as a beat cop in Kowloon City, said: “Most residents were not involved in any crime and lived peacefully within its walls, but sadly, under appalling conditions – with no running water, street lighting, electricity or sanitation.

“My personal experience dates from 1963. By that time, regular uniformed patrols were conducted 16 hours a day, seven days a week.”

He was posted to the Kowloon City division in the 1960s, and in the next decade, served at the Kowloon police headquarters overseeing vice raids.

When the death knell sounded for Kowloon Walled City – Hong Kong’s ‘dirty old wart’

“What was special about the Kowloon Walled City at the time, I think, centred on other forms of government neglect and illegality, such as unlicensed dentists, doctors, food processing plants and small manufacturing, as well as the often primitive circumstances under which people lived, with only a standpipe water supply, little or no legal electricity and no drainage,” he said.

The former residents who talked to the Post said the experience of living in the Walled City toughened them.

Family doctor Chan now lives in a two-storey house with a small garage in America – a vastly different life from her time in a 600 sq ft flat on the 10th floor of a cramped building in the Walled City.

“The indelible memory I have of the Walled City is the impression that poverty can drive people to desperate measures in their scramble for survival.

“In those days I often came across junkies who slept under the stairs and would do anything just to get money to buy drugs. One time, when I was still a primary school kid, a young junkie held me at knife point asking for money,” she recalled.

I often came across junkies who slept under the stairs and would do anything just to get money to buy drugs

Chan said she was so frightened that she burst into tears, which caught the junkie by surprise and caused him to flee.

Retiree Lau, who came to Hong Kong from Fujian in 1974, said that while he was working at a toy factory, his boss told him about cheap homes in the Walled City.

He bought a flat for his family in the late 1980s for around HK$40,000 (US$5,100)

“Everyone stayed there for so long and no building collapsed,” he said. “I didn’t see any fires either.”

But he acknowledged that it was inconvenient to get fresh drinking water.

“We had to go to a nearby public tap to draw buckets of water for drinking and cooking,” Lau said. They also used water from a well for washing clothes and flushing the toilets.

Another retired officer, who asked not to be named, said: “I was posted to Kowloon City in 1987 and often patrolled the Walled City. I occasionally went to the roofs to watch the planes skim over the top and land at Kai Tak [the old airport].”

He said it was an urban myth that police did not patrol the slums.

Once reviled, Kowloon Walled City is now regarded as an example of ‘organic design’

“We often went in there ... It’s just easy to lose someone if you are chasing them in the Blade-Runner-like mazes. There were fishball sellers and [illegal] dentist clinics. Night and day within the Walled City were the same, with buzzing electrical wires, dripping pipes and years of detritus packed between the walls.

“The rats were something else and often ran down the streets with their eyes shining red under my torch. Kids going to school always emerged from the place in their pristine white uniforms, which amazed me. One of my best sergeants lived and grew up inside.”

The rats were something else and ran down the streets with their eyes shining red

While Lau wanted to stay there, he accepted compensation of about HK$120,000 and used it to buy another flat in a nearby tenement building, where he is now living with his wife, as well as a son and daughter. His three other children have moved out.

For him, memories of people in the Walled City were always in a positive light.

“The kaifong were very close,” Lau said, using an affectionate Cantonese term for neighbourhood residents. “For example, when I bought soy sauce and other goods from a store downstairs, the owner would ask if I wanted them to be delivered up. I said: ‘I am still young and have my arms and legs, so I don’t need the help.’”

American resident Chan said, however, that she was glad to see the Walled City converted into a refreshing park. “I was back once and I found that the park was really clean and rejuvenating.

“Do I miss this place? I don’t think so because it was really unhygienic, dirty and seedy. But I do admit that it had a unique culture that you won’t find outside.”