What happens when Hong Kong’s ethnic minority students are separated at school from ethnic Chinese children?

Limited educational resources for minorities, combined with some parents’ apprehensions, account for divergent experiences and opportunities, new study finds

When Aruna Rana started looking for a kindergarten in Hong Kong for her two children, she wanted them to be immersed in a Chinese-speaking environment. After all, and despite their Nepali heritage, the city had been her family’s home for three generations.

But finding a school willing to accept them was more challenging then she had ever imagined.

“It was a complete nightmare,” she recalled. “It was very hard to enrol my children in a local kindergarten. The vibe we got was that they did not want them there.”

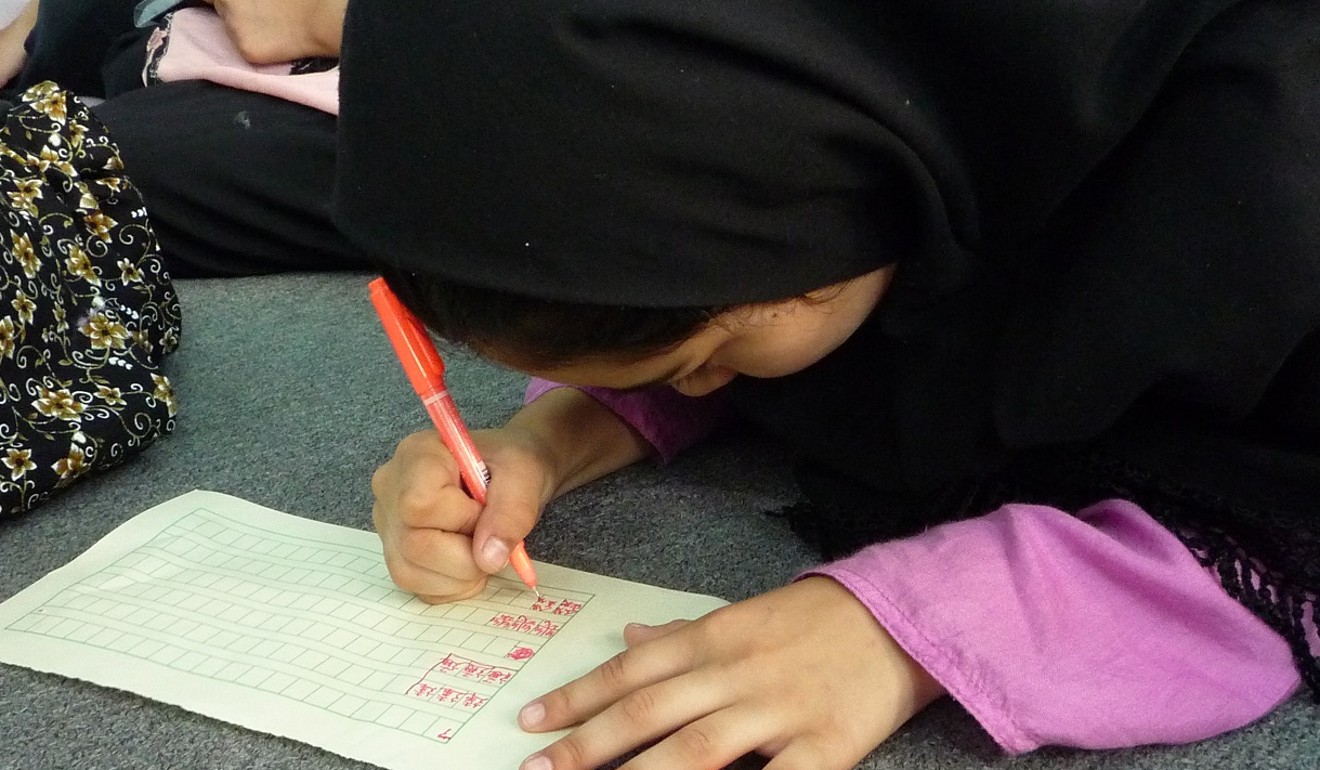

A study released on Monday shines a light on the segregation that ethnic minorities in the city face from an early age. It found that many kindergartens do little to promote multicultural interaction between children, as teachers struggle with a lack of instructional resources and materials for non-native speakers to learn the Chinese language.

Some kindergartens also avoid accepting pupils from ethnic minorities because that dissuades Chinese parents from enrolling their children, according to social policy think tank the Zubin Foundation.

There are about 250,000 people from ethnic minorities in Hong Kong, accounting for 3.8 per cent of the city’s population, according to government figures which did not include the city’s hundreds of thousands of foreign domestic workers. The surveyed kindergartens – of which 29 were Chinese-medium schools – were selected from the six districts with the highest percentages of ethnic minority residents.

Foundation project manager Maggie Holmes, one of the study’s authors, believed the heart of the problem to be a lack of instructional resources for teachers, who are often busy and have difficulty giving individualised attention.

“More schools would be comfortable taking ethnic minority children if they had readily available resources,” Holmes said. “Our impression is that many wanted to help, but they felt they could not. We desperately need resources made by experts for teachers, so they know how to help this group of children.”

More schools would be comfortable taking ethnic minority children if they had readily available resources

No centralised and structured support programme currently exists for students from non-Chinese-speaking family backgrounds at kindergarten, according to the research. “Principals and teachers make their own materials on an ad hoc basis. If at all,” the study found.

At the same time, “teachers do not feel confident that they understand how best to support ethnic minority students in their class. Teacher training is needed,” it added.

Holmes suggested using jyutping – a romanisation system for Cantonese – in allocating resources for ethnic minority students and hiring education ambassadors from their community to advise parents.

More than 40 per cent of kindergartens in Hong Kong do not have any ethnic minority students, the study also found. Yet, at some local kindergartens, ethnic minority children make up more than 90 per cent of the cohort, meaning their interaction with native Chinese children is highly limited.

“Parents are turned away from kindergartens on the basis of their race or lack of Chinese speaking ability,” the study continued. And “the presence of ethnic minority students in a kindergarten is a deterrent to Chinese parents who don’t want their children in the same school or class as ethnic minority children”.

Racism is alive and well in Hong Kong, but there’s growing sympathy for refugee children

Some schools admitted separating children into different classes according to their race.

“Ethnic minority parents ask us why their children are not in the morning class,” a school principal interviewed for the study said. “Because if we give a morning place to a non-Chinese-speaking student, the Chinese parent will move out.”

In February, local officials announced that a steering committee on ethnic minorities would be set up and that HK$500 million (US$63.7 million) would be allocated to strengthen support for them. However, more needs to be done, according to experts and ethnic minority residents.

Rana, who also has a 13-year-old daughter fluent in Cantonese, urged officials to bridge the education gap and offer more financial support for children who want to learn the language. Many parents were unable to afford private tutors, she added.

The hidden racism plaguing Hong Kong, and how one student is fighting back

“The government should really think about how to involve more ethnic minority kids in the mainstream schools ... and how to give us the opportunities we deserve. We have been working really hard so our kids’ generation can at least be part of society in the way that they want to be.

“We have to mingle and be together.”