A child emperor, agarwood, adding oil and ordering wishes – stories behind Hong Kong words

What’s in a name and what do some endearing terms in the city mean? City Weekend breaks down five examples

While some names of Hong Kong districts, foods and certain ubiquitous Cantonese phrases are well known among foreigners and conveniently adapted into English, there is no better way to understand the cultural glue that binds Hongkongers than to dive into the stories behind them.

Hong Kong

The English name for this jam-packed city of more than 7 million derives, perhaps unsurprisingly, from its Chinese name, the characters for which first appeared in Yue Da Ji, a Ming dynasty (1368-1644) publication. But where did the name heung gong – the “fragrant harbour” – come from?

Among various theories, the most widely accepted is Hong Kong’s history as a producer of incense, specifically agarwood. The village and surrounding bay from which the agarwood was harvested and transported was known as heung gong.

When the British first docked in Stanley, a local Hakka man informed them the name of the bay. The British apparently assumed this referred to the entire island, and thereafter the romanised name “Hong Kong” stuck.

You could never replace Cantonese as the language of Hong Kong

Kowloon

The Chinese characters for the peninsula just across from Hong Kong Island translate to “nine dragons” – a reference to eight hills and a child emperor.

After people from the southern Song dynasty in present-day Hangzhou fled from Kublai Khan and his invading Mongols in 1276, the dynasty’s remnants, including an emperor’s son called Zhao Bing, were pursued across territories by their enemies.

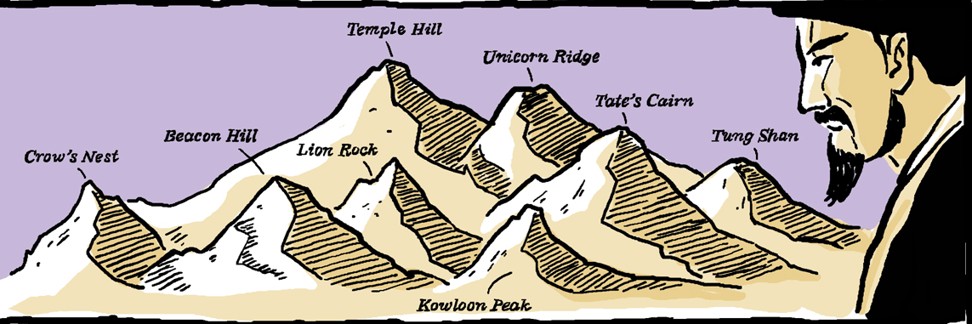

Zhao Bing and his court eventually arrived in present-day Hong Kong, where he was enthroned. He saw the eight peaks – Beacon Hill, Crow’s Nest, Kowloon Peak, Lion Rock, Tate’s Cairn, Temple Hill, Tung Shan, and Unicorn Ridge – and imagined eight dragons in their place. Imperials reminded the emperor that rulers were also prestigiously deemed dragons and, therefore, the place was called “nine dragons” to honour the child monarch.

Mandarin may be king, but it can’t sideline Cantonese in Hong Kong

Dim sum

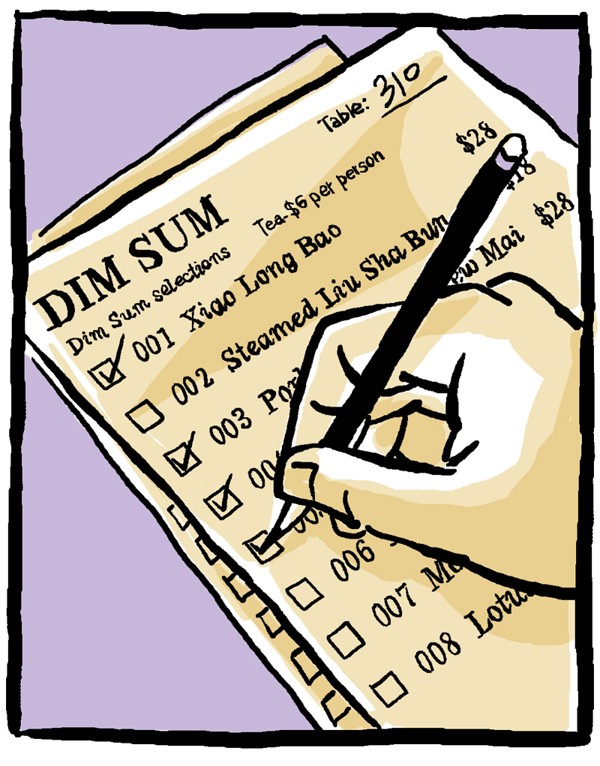

The well-known term is used to describe a collection of small bite-sized Chinese dishes ranging from buns to dumplings and served on porcelain plates or in steamer baskets. A selection of tea accompanies the meal.

The Chinese characters for “dim sum” translate into “a touch of the heart”, befitting the love affair Hongkongers have for generations had with the meal, and bonding time between companions over choice morsels.

However, some argue that this is false etymology based on the individual definition of each of the two Chinese characters that form a compound term.

The alternative meaning of “dim sum” is therefore “to order wishes”, in which the Chinese character “dim” means to place an order for food, and “sum” translates into heart, which could also be interpreted as an intention or wish.

Hong Kong’s best dim sum modernised by chefs using healthier ingredients and innovative techniques

While dim sum is usually had in the morning or early afternoon and most tea houses switch to full dinner meals by evening, it has become hip for some restaurants to continue serving the cuisine throughout and brand themselves dim sum houses.

Yum cha

The two words literally mean “drink tea” in Cantonese, but it has to be interpreted in context – it is usually used in an affable manner to mean the act of having Chinese tea and dim sum or, more generally, catching up over a small meal.

The origin of the words “yum cha” can be said to date back to the time of the Xianfeng emperor, the ninth ruler in the Qing dynasty line, from 1850 to 1861. Tea houses serving beverages and a range of small dishes at the time were places that people gathered to hang around, gossip or just to enjoy a meal. In modern times, the activity is particularly popular among retirees for whom many hours can be spent shooting the breeze with old friends at the table.

However, the term can also be used to mean the equivalent of the Western phrase “Let’s go grab a drink some time”, or even “See you later”. Hongkongers who say this when they run into an acquaintance on the street could just be using the term out of politeness. Neither side may be in a rush to fix a date.

Gaa yau

“Keep going! You can do it! You’ve got this! Keep your chin up!” These are all ways of cheering someone on in English. The most commonly used Chinese idiom for this, however, invokes a metaphor. “Gaa yau” is Cantonese for “add oil”, which is better understood in English as “to refuel” and to keep pushing ahead.

That said, there was no better, or more literally apt, occasion to say “gaa yau” than in the 1960s during the Macau Grand Prix. Spectators back then started chanting the term to inspire drivers to accelerate by putting the pedal to the metal and, well, adding oil.