As heritage and historic buildings succumb to redevelopment, is it too late to save old Hong Kong from the wrecking ball?

Preservationists say society must come to its senses before the city loses its diverse mix of new and old structures

Hong Kong has two faces – one looks to the future, the other to the past. But seldom do both see eye to eye.

The perpetual sound of jackhammers and drills across the urban landscape is a constant reminder of this battle between modernisation and preservation.

Behind the gleaming glass of skyscrapers and luxury shopping malls lingers the fraying fabric of old Hong Kong – traditional tenement blocks, shophouses, elegant Chinese mansions and awe-inspiring colonial relics.

But today, in the world’s most expensive property market, even buildings with major historical or heritage value are giving way to redevelopment, as land becomes increasingly scarce.

The government in 2009 identified 1,444 ageing structures as eligible for varying degrees of protection. But almost 50 have since been demolished or significantly altered – to the angst of preservationists.

“The pace of conservation, especially in a fast-changing city like Hong Kong, must keep up with the pace of development,” said Lee Ho-yin, who leads the University of Hong Kong’s division of architectural conservation programmes.

Anglican church defends high-rise hospital plan for heritage site in historic heart of Hong Kong

“To stand out amid the global competition for investment and talent in the 21st century, a city must have a heritage identity as well as modern infrastructure. A diversified built-up environment with a mixture of new and old, and tall and low buildings, is a must for any attractive city.”

The 1,444 buildings were grouped into three grades based on their heritage value, but none enjoy legal safeguards against demolition or alteration. That honour has been afforded to only 117 structures declared monuments.

Hong Kong Central Police Station restoration: how city’s most ambitious heritage project overcame the odds

About 80 per cent of the 1,444 buildings are privately held by owners who are free to tear down the properties to cash in on the value of the land. A number have been tempted to do so, and some have pointed the finger at officials. They say conserving and repurposing old buildings is difficult, and the government provides little support.

Ghosts of Hong Kong past

Among the buildings no longer standing is Ho Tung Gardens, a grade one historic mansion with “outstanding merit, which every effort should be made to preserve if possible”, according to official classifications.

Built in the 1920s, the 120,000 sq ft former home of late tycoon Sir Robert Ho Tung was hailed by antiquities authorities as a masterpiece of Chinese renaissance architecture.

In Yangon, more colonial buildings are being preserved as homeowners realise they can profit from heritage

Set on The Peak, one of Hong Kong’s most exclusive neighbourhoods, the property featured a two-storey main house and Chinese garden with a five-storey pagoda and pavilion.

The main building was demolished in 2012 by then owner Ho Min-kwan, a granddaughter of the late businessman. The site was sold three years later to mainland tycoon Cheung Chung-kiu for a then record sum of HK$5.1 billion (US$650 million).

Redevelopment work began earlier this year to build a pair of three-storey luxury residential blocks on the site.

Heritage buildings in Hong Kong: why conservation has never been a priority

Also succumbing to the wrecking ball have been three shophouses on Lee Yick Street in Yuen Long built between the 1890s and 1950s. They were grade two historic buildings, for which “efforts should be made to selectively preserve” the properties, authorities said.

Tung Tak Pawn Shop in Wan Chai, built in 1942 and listed as grade three, was also torn down, in 2015. This came despite officials recommending that “preservation in some form would be desirable and alternative means should be considered if not practicable”.

Old buildings, new life

The Reverend Peter Choy Wai-man, who heads a heritage revitalisation project by Hong Kong’s Catholic diocese, said sky-high land and property prices meant demolition was attractive for private owners, especially in urban areas.

“Maintaining antiquities often involves a lot of resources and is much less cost-efficient,” Choy said. “Tearing them down for redevelopment is in many cases simpler and more profitable.”

Central Police Station is now the Tai Kwun Centre for Heritage and Arts, where fond Hong Kong tales live on

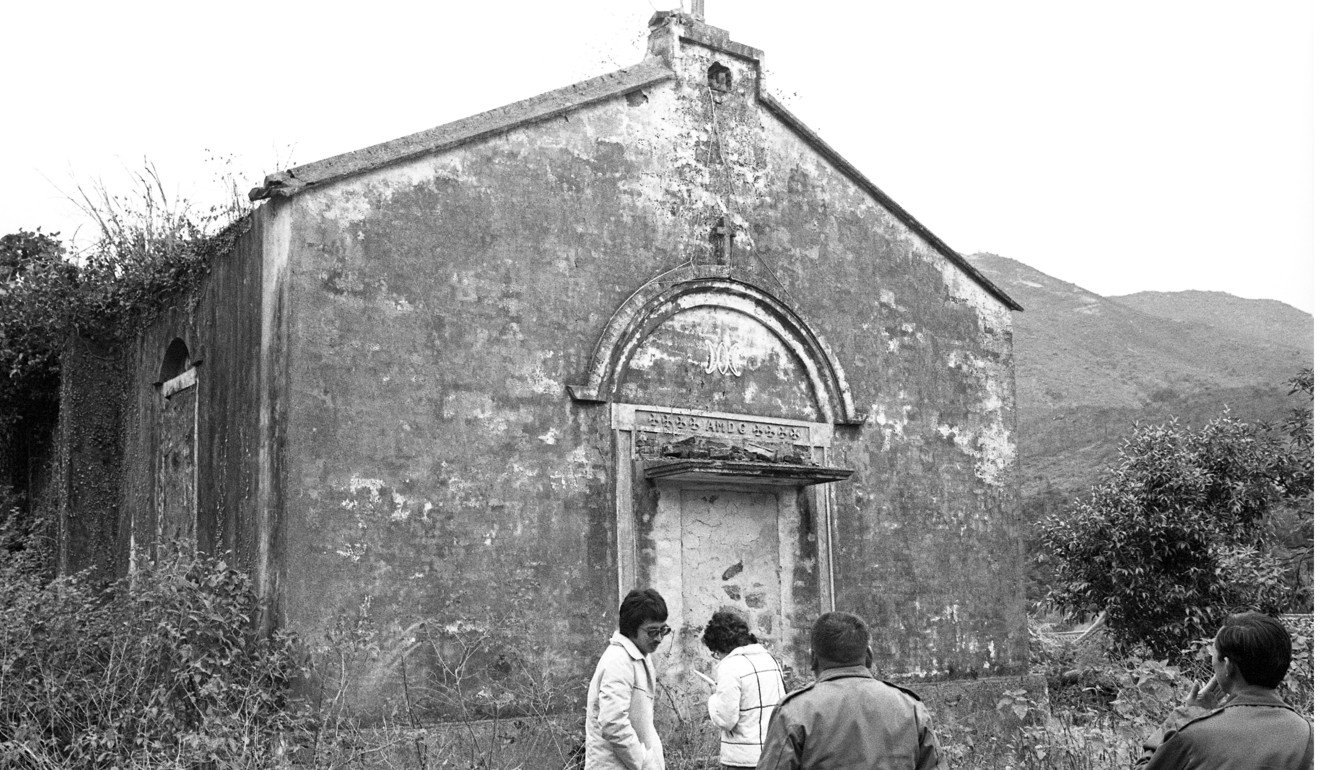

His initiative, named Following Thy Way, is looking to revive and restore 11 dilapidated churches on the Sai Kung peninsula in eastern Hong Kong – two of which are historic buildings. The structures are abandoned and have largely fallen into disrepair, but the diocese wants to create a “pilgrimage trail” along a hiking path near the churches.

“After revitalisation, it will become a heritage trail,” Choy said.

Along the route is the 151-year-old Holy Family Chapel in Chek Keng, a grade two historic building, and the 138-year-old Immaculate Heart of Mary Chapel in Pak Sha O village, listed as grade three.

The project team is applying for funding from the Development Bureau’s Financial Assistance for Maintenance Scheme, which helps private owners with preservation.

Seven Hong Kong colonial heritage buildings to see when they open doors to public, offering a rare peek inside

The cost of repairing each chapel has been put at HK$15 million, Choy said, but government funding is capped at HK$2 million per application. Owners can apply multiple times for one building, but it means protracted construction times and costs, according to Cheung Chun-kin, an architect representing the project.

Each application takes about six months to process and requires hiring consultants and contractors through public tender. Multiple submissions therefore result in ballooning costs.

“I would prefer a more flexible funding cap, enough to cover one project or at least one phase of a project,” Cheung said.

Experts were also needed to help private owners navigate the complex process, he added.

Yuen Chit-chi, owner of the grade two Yuen’s Mansion in Mui Wo, agreed.

Heritage conversation is not a priority in Hong Kong where the profit motive prevails

The property’s age and surrounding construction work mean six buildings on the site, built between the 1920s and 1940s, have been damaged by flooding and ground vibrations from heavy machinery.

Yuen said he wanted the government subsidy, but did not know how to apply.

“We are country people who know nothing about this technical stuff, and hiring consultants to help us is expensive,” Yuen said. “The government has never actively come to discuss it with us or help.”

Between 2008, when the funding scheme was introduced, and March this year, there were 130 applications. Only 42 per cent were approved.

Market value vs historical value

Lee believed there should be legal protection for these buildings, and Singapore provided a good example.

The Lion City carved out entire areas for conservation rather than just individual buildings, he said. Structures facing main streets in these neighbourhoods must be strictly preserved and redevelopments behind them subject to strict height restrictions.

Hong Kong’s post-war heritage building grading needs to be placed in the hands of specialists

Also not permitted is the purchase of several neighbouring sites with a view to combining them for construction of a larger building.

The rules had encouraged private owners and developers to conserve and repurpose old buildings, which had added value to these districts, Lee said.

“Hong Kong’s property market at the moment is a bubble – it will burst sooner or later,” he said. But buildings with historical value would maintain their worth, Lee believed, no matter what happened to the market.

Tai Hang in Causeway Bay, Tai Ping Shan in Sheung Wan, and some parts of Sham Shui Po and Yau Ma Tei had potential as conservation zones, the academic said.

Car crash fells wall at Hong Kong’s historic Wan Chai police station, but compound’s heritage value survives

Some organisations are already fighting for the preservation of parts of their own districts.

In January, the Central and Western Concern Group applied to city planning authorities to turn Government Hill and neighbouring Bishop Hill into a conservation area with height restrictions.

The move was to counter a plan by the Hong Kong Anglican Church to build a 25-storey private hospital, which would dwarf surrounding structures.

“The heritage fabric of Hong Kong exists not only in individual buildings, but also in the streets that link them,” group convenor Katty Law Ngar-ning said.

“Taken out of their surrounding neighbourhoods, historical buildings mean so much less to society.”

The group’s application is due to be discussed by the Town Planning Board early next month.

Walking tours of Hung Hom, To Kwa Wan and Kowloon City aim to keep memories of old Hong Kong alive

Hugo Chan Chun-kwok, a lecturer who works with Lee at HKU, said that, with much of old Hong Kong rapidly giving way to the demands of the modern economy, officials and society at large must urgently realise and harness the cultural value of the city’s remaining architecture from yesteryear.

The academic recently led a group of students on a conservation field trip to Shanghai, which he said had already adopted many of Singapore’s policies, despite its own rapid and transformational pace of development.

By Chan’s reckoning, time is fast running out in Hong Kong, even more so than for its northern cousin.

“Hong Kong started to develop very fast in the 1970s, much earlier than Shanghai and long before heritage conservation was much talked about,” Chan said.

“In this time many historical buildings have already disappeared ... If we don’t start preserving soon, we may never be able to.”

Reader response:

Why heritage conservation in Hong Kong is a losing battle