No way out: How Hong Kong’s subdivided flats are leaving some residents in fire traps

One family’s escape from a blaze at a Cheung Sha Wan building highlights risks from bad fire safety at buildings housing many more people than they were designed to. But the law restrains officials from acting

At 5am on February 16, Wu Caiyun thought she was having a horrible nightmare when her 12-year-old daughter shook her awake, screaming at the top of her lungs: “Mum, there’s a fire!”

After having been suddenly woken up mid-sleep, nothing seemed to make sense to Wu at first. But as she opened the front door, reality sank in quickly. Her minuscule 130 sq ft flat was engulfed by choking black smoke that continued to pour in.

The smoke was coming from a fire, caused by a carelessly discarded cigarette, that was tearing its way through another subdivided unit on the third floor, right beneath Wu’s.

Smoke spread through the entire building, on Un Chau Street, Cheung Sha Wan, within minutes. As the light well and windows along the communal staircases were all boarded up, residents found themselves trapped in their flats.

“All we could think about was trying to find a way out. We certainly didn’t want to die here,” Wu said.

Wu, her husband and their daughter ended up escaping through a back door hidden behind their bunk bed that they had never opened in the 11 years they had lived there.

“At the time, we didn’t know that it would lead to a back staircase or if it would even open at all. But we thought ‘if there’s a door, there must be a way out’ so we pushed it open,” she said.

The flames tore through the entire seven-storey building in a short time.

There were no serious casualties, but the accident has raised alarm over the tens of thousands of Hongkongers currently living below the poverty line and forced to inhabit similarly dangerous subdivided homes.

According to government figures, there were nearly 200,000 people living in some 88,000 subdivided flats in 2015. And about 57,100 of those households – 65.2 per cent of the total – lived in units from 75 sq ft to 140 sq ft.

Most subdivided units are found in old tenement buildings, or tong lau, and the majority of them are in Hong Kong’s poorest district, Sham Shui Po, where Wu and her family live.

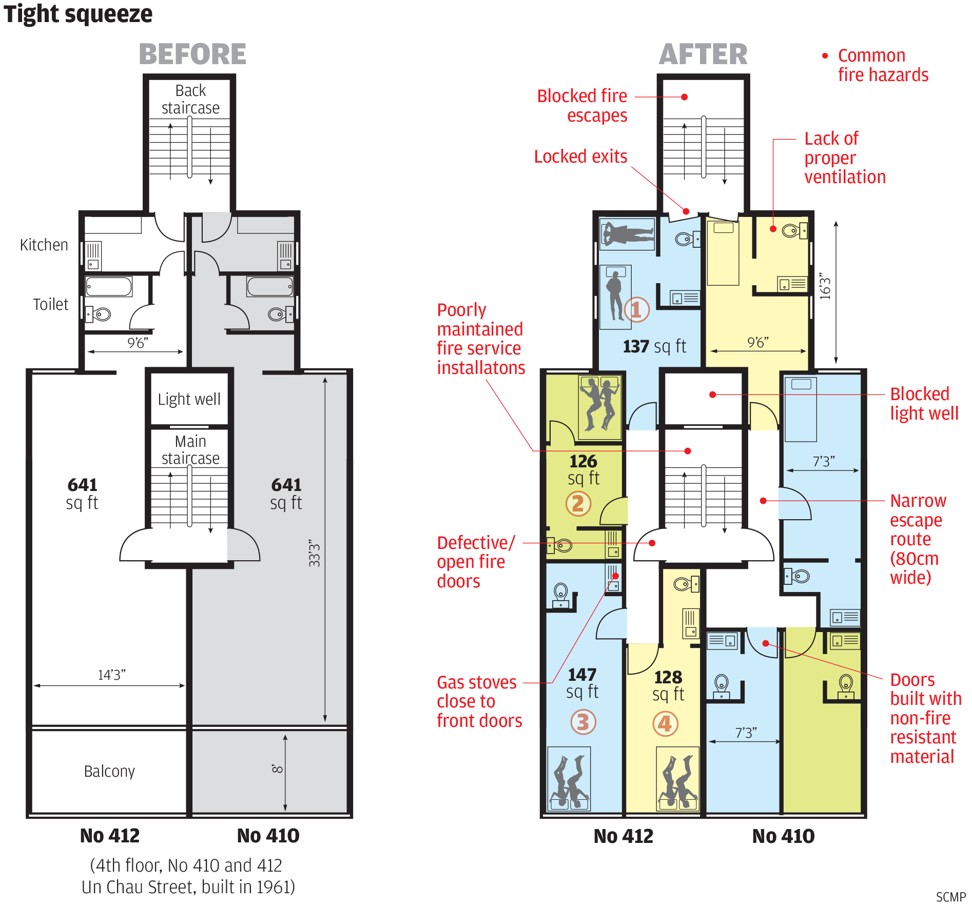

Built in 1961, the building where the fire broke out was supposed to house up to 14 families.

The original floor plan for the level where Wu and her family were showed two 641 sq ft flats, each with a balcony. But these apartments had each been split into four smaller flats, to maximise the number of tenants. Other floors had similar alterations.

When the fire hit, there were at least 38 families living in the building, according to non-profit group Society for Community Organisation (SoCO), which is helping affected residents in the aftermath of the fire.

Most of these partitioned cubicles fall into a legal grey area and are tolerated as long as they comply with fire safety and building standards. But alterations to divide flats into smaller units rarely adhere to proper standards, meaning they are often fire traps that put people at risk if a fire breaks out, according to surveyor Vincent Ho Kui-yip.

The Fire Services Department does not hold statistics on the number of fires that involve subdivided units, but news archives reveal there were nine blazes in the first four months of this year alone, three of them fatal.

Ho, who accompanied the Post to inspect the Cheung Sha Wan building, pointed out that makeshift corridors were too narrow, fire escape routes were blocked by discarded furniture and miscellaneous household items, and fire doors were either defective or left open.

“Without proper fire-resistant doors and partitions, the fires could spread easily from one apartment to another,” Ho said.

One of the reasons why the proliferation of substandard flats persists is because government officials face difficulties in carrying out safety inspections, while applying for court warrants and prosecutions takes time, experts have said.

“Even if the government receives a lot of complaints about unauthorised subdivided flats, the problem is that officials cannot even enter the apartment because of privacy concerns,” said Simon Yau Yung, an associate professor at City University.

“Landlords today are also much smarter than they were before... making it harder for officials to spot the alterations,” Yau said.

According to Yau, subdivided flats in old buildings used to have multiple letter boxes and electricity meters. Now landlords just use one electricity meter to split the entire bill and charge by household size, to avoid detection.

Professor Chau Kwong-wing, a housing expert at the University of Hong Kong, said there is not enough manpower at the Buildings Department to enforce regulations in what is a repetitive and time-consuming process.

Each year, the government inspects about 100 buildings, or 3,000 subdivided flats, to act on unauthorised works. But a Legislative Council panel has slammed the government for “unsatisfactory performance” in taking down unauthorised structures.

Despite an increase in reports of unauthorised building works, the government has of late been removing fewer of the structures than before, according to the Public Accounts Committee panel report in 2015.

The number of reports of unauthorised building works almost doubled to an average of 42,124 a year between 2011 and 2014, compared with 23,947 a year from 2001 to 2010. But the number of removals of the structures had dropped from 40,526 to 17,325 per year in the same period.

There were still some 68,000 outstanding removal orders by the end of 2014, 20 per cent of which had not been dealt with for up to 10 years. Some 753 cases were untouched for up to 30 years, the report revealed.

Yau, of CityU, said the key to deterring landlords from badly partitioning flats would be to give officials more power to enter flats.

“If speculative landlords know that the officials have no actual power to enter their flats for inspection and cannot establish a case for prosecution…[any other solution, like tougher penalties] would just be all bark and no bite,” Yau said. Under such changes, an official of a certain rank could only enter premises with the authorisation of the director of buildings, while holding enough observational evidence.

The Development Bureau said it was working on a legislative proposal to strengthen the Buildings Department’s powers regarding entry, but the plan is only aimed at illegal homes in industrial buildings, not residential buildings.

The bureau said existing laws were sufficient to help officials enforce the rules in subdivided flats.

Yau disagreed, saying Hong Kong could benefit from a separate law clearly defining subdivided flats and the related penalties, making it easier to prosecute landlords who break the rules.

In New York City, subdivided units are considered illegal home conversions, and landlords can be fined between US$500 to US$25,000 for having them.

A major bill is being proposed in the city to impose steeper fines and help inspectors access premises. Under the proposal, landlords could be fined at least US$45,000 for flats that have at least three subdivided units.

Chau, from HKU, disagreed with the need for a separate law. “There is no short-term solution to this unfortunately,” he said. “You cannot have a separate building code for subdivided flats as they are [not supposed to happen] in the first place.”

Chau instead said demand for subdivided flats would go down when land supply increases and homes become more affordable.

For the residents who have to deal with the aftermath of the fire, such proposals are not the real solutions. Jennie Chui Pui-yan, a social worker from SoCO, said that these residents are often the most vulnerable, since the buildings they live in often don’t have an owners’ corporation, building management company or residents’ group.

“What these residents really need now is to have the building facilities fixed to make sure they’re living in a safe environment. Residents have complained of unstable electricity supply and a lack of fire safety equipment, but their complaints often fall on deaf ears,” Chui said.

Two months after the fire, the landlords covered up fire-blackened walls with a coat of white paint, put up more light bulbs in common corridors and replaced broken-down doors in an attempt to give new life to the building, but the trauma still haunts the place.

Chen Shuiqing, whom firefighters rescued along with her husband and three sons through a window of their apartment, said that the emotional distress was the hardest to deal with.

“I try not to think about the bad things, but my four-year-old would still wake up shaking from nightmares in the middle of the night,” Chen said.

Some families have moved out since the fire in February and many are still looking for new homes, according to Chui.

But Wu and her family returned to their old flat and pay the same monthly rent of HK$4,300. Asked if she would move elsewhere, she shrugged her shoulders and said: “Even if we moved, wouldn’t the situation be just the same wherever we go? With what we are earning, we can only afford to move to another subdivided flat in another old building with the possibility of another fire breaking out.”