How big data and covert surveillance are helping tackle Hong Kong’s problem of illegal dumping

From a trove of government data, HKU associate professor identified 442 vehicles suspected of illegal dumping

Academics are hesitant to have their work associated with “activism”. But big data scientist Dr Wilson Lu Weisheng has no qualms about his latest work being described as such.

His project will involve gritty field work – covert surveillance and making use of hidden “ambush cams” to record the movements and capture the licence plates of hundreds of dumper trucks, a sizeable contingent of which he suspects are involved in illegal dumping.

“It will be a more thrilling research project than just digging out numbers,” said the associate professor at the University of Hong Kong’s department of real estate and construction.

Lu has developed an analytical model to find just what portion of the city’s construction and demolition waste is actually disposed of unscrupulously.

From a trove of government data he secured – 7.8 million dumper truck trips to public landfills over the last six years – 442 out of 10,000 registered vehicles were identified as “highly suspicious” of being involved in illegal dumping activity.

“We have data on almost every recorded truckload of waste dumped at landfills over the last six years. But finding out how many trucks are involved in illegal dumping is like finding a needle in a haystack,” Lu said.

“With data mining, we can find it. But these [442] cases are just the tip of the iceberg.”

Hong Kong work sites send about 4,200 tonnes of construction waste to the tips every day, comprising more than a quarter of all the city’s landfill.

The Environmental Protection Department has struggled to grasp the true scale of the problem and introduce measures to tackle it, according to Lu.

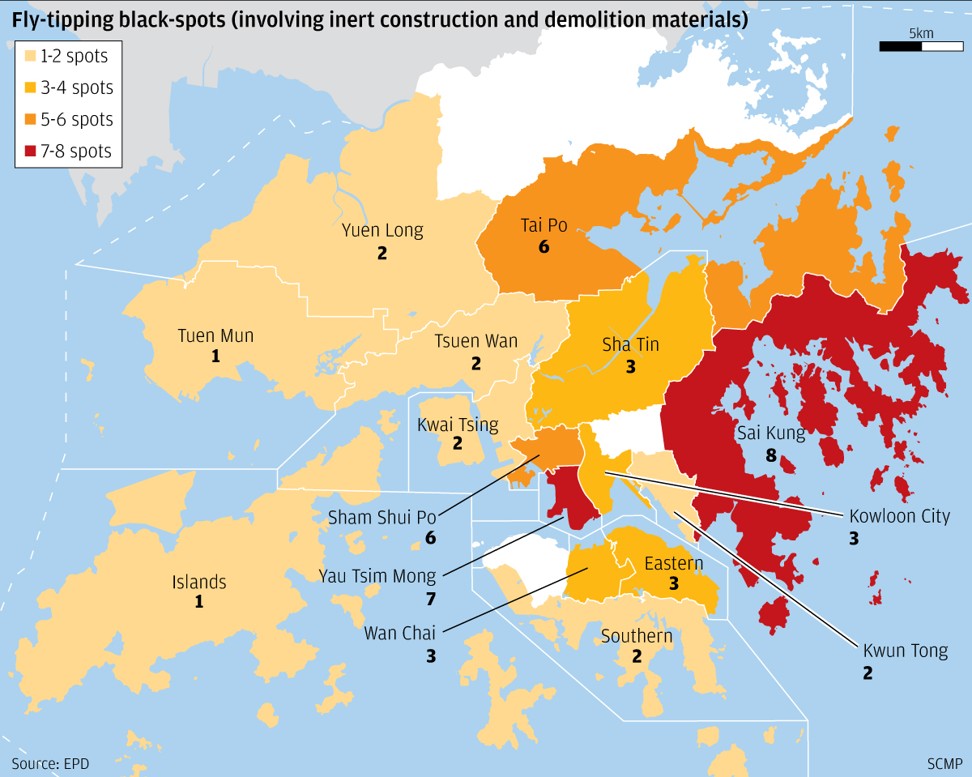

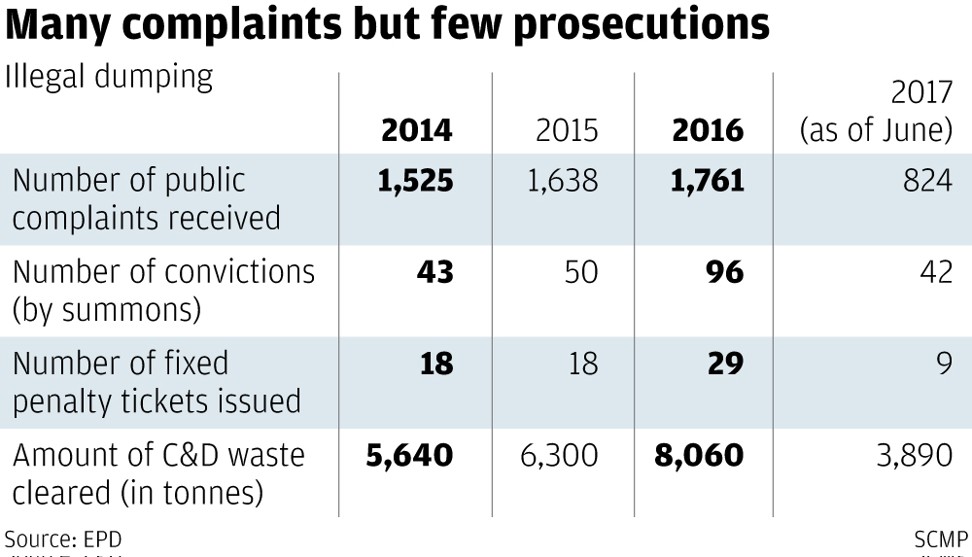

Last year, the Audit Commission slammed the department for lax enforcement, with the number of reported cases of illegal dumping of construction and demolition waste across the city tripling from 1,500 in 2005 to 6,500 in 2015.

Such cases are rampant across the New Territories. At least a fifth of unauthorised development cases over the last two decades involved illegal filling of fish ponds, which is destroying wetland ecosystems, according to environmental group WWF-Hong Kong.

Fly-tipping is a convenient way for contractors to avoid paying tip fees or to save on transport time and costs. Illegally disposing a load of construction waste can generate cost savings of up to HK$3,750 in tip fees, depending on the volume and type of waste, excluding savings in transport costs – roughly HK$800 to HK$1,500 per trip – as well as wait times at public fills, said Lu.

Lu incorporated a technique called decision-tree modelling, which scholars in Europe were already using to identify activities like credit card fraud.

With their licence plate numbers, Lu was able to identify them in the government database and use their common characteristics to “train” the analytical model to identify and “filter out” all suspicious cases.

“If they are focused on selling services to just one contractor, they are more prone to illegal dumping,” Lu said. “If they usually have to travel longer distances to the landfill, it raises incentives to cheat.”

Other high-risk indicators included whether the consistently queued for long-periods at a public fill – less patient ones are more illegal dumping prone – and whether they handled hauls from private projects rather than public ones.

Lu stressed that anything identified by big data would be inadequate for prosecution use.

“But they can be used by the government for more cost-efficient targeting and enforcement. For example, the EPD can conduct ambushes and inspections on suspicious plate numbers I provide.”

The next step of the study, which he is now seeking funding to continue, is to collect more plate numbers and widen the parameters to find more cases of suspected illegal dumping.

A department spokeswoman said the EPD did not keep any records on the number of vehicles involved in illegal dumping. It did. however, have to clean up 8,000 tonnes of illegally dumped construction waste last year, about 25 per cent more than the year before.

The department is considering the use of surveillance cameras at black spots and legislating use of GPS on dumper trucks to curb the problem.

“We will also keep in view the developments of relevant research and technological developments in considering further measures to facilitate our enforcement actions.”

There were 1,761 cases of illegal construction waste dumping last year leading to 96 convictions, up from 1,638 complaints and 50 convictions in 2015.