Hong Kong teen’s dreams of being a doctor dashed by education system’s failure to teach Chinese to ethnic minority students

Education group Unison says schools aren’t getting the proper guidance to teach pupils who grew up in a non-Chinese speaking environment

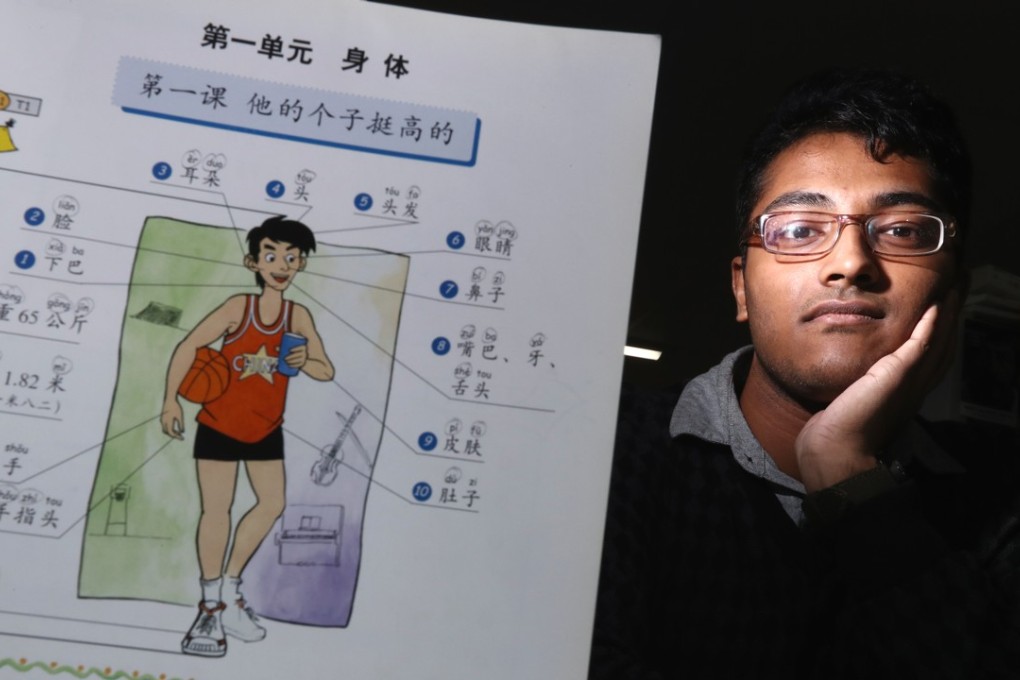

Siddhartha, a Hongkonger originally from Bangladesh, always wanted to be a doctor but an inability to speak Chinese ended his journey before it began.

The 19-year-old said his ability to speak and write in the language was at the level of a Primary 2 pupil, and admitted he had not known he would need to be proficient in both to pursue his chosen career.

He only found out his chances of becoming a doctor were slim when he went to University of Hong Kong (HKU), and Chinese University (CUHK), the only two institutions in the city offering a degree in medicine – which is taught in English – before his Diploma of Secondary Education (DSE) exams two years ago.

“Both schools’ deans and admission officers told me that being able to speak Chinese is part of their interview process, which is understandable because patients in Hong Kong are mostly Chinese.

“But up until that point, I had no idea,” Siddhartha said.