Explainer | How a history exam question stirred up controversy over China, Japan and Hong Kong’s education system

- The question in the DSE history paper asked if Japan ‘did more good than harm to China’ between 1900 and 1945

- Observers say the furore affected not only the 5,200 students who sat the exam, but has wider implications for Hong Kong

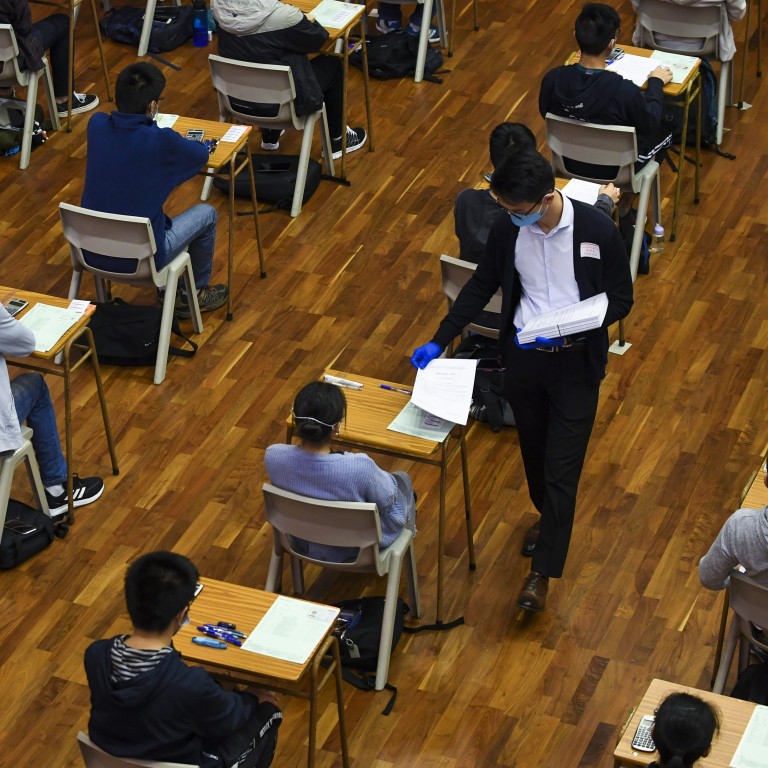

On Friday, Hong Kong’s Education Bureau took the unusual step of ordering the city’s independent examinations authority to strike out a question from the Diploma of Secondary Education (DSE) history paper.

The offending question focused on the relationship between Japan and China in the first half of the 20th century, including the World War II years.

What set off the storm was the way the question was worded, as well as two accompanying readings. It asked if Japan “did more good than harm to China” between 1900 and 1945.

Pro-establishment politicians and teachers in Hong Kong were outraged, as was the Chinese foreign ministry, before the Education Bureau stepped in to declare the question off-limits and insist on its removal.

The question was criticised as one-sided, and said to have hurt the feelings of Chinese people who remember the atrocities committed by the Japanese while the two countries were at war.

State news agency Xinhua said in a strongly worded commentary on Friday night that if the exam question was not struck out, the “rage of all Chinese sons and daughters would not be able to be settled”.

Observers say the furore affected not only the 5,200 students who sat the exam, but has wider implications for Hong Kong.

What is the question that sparked the row?

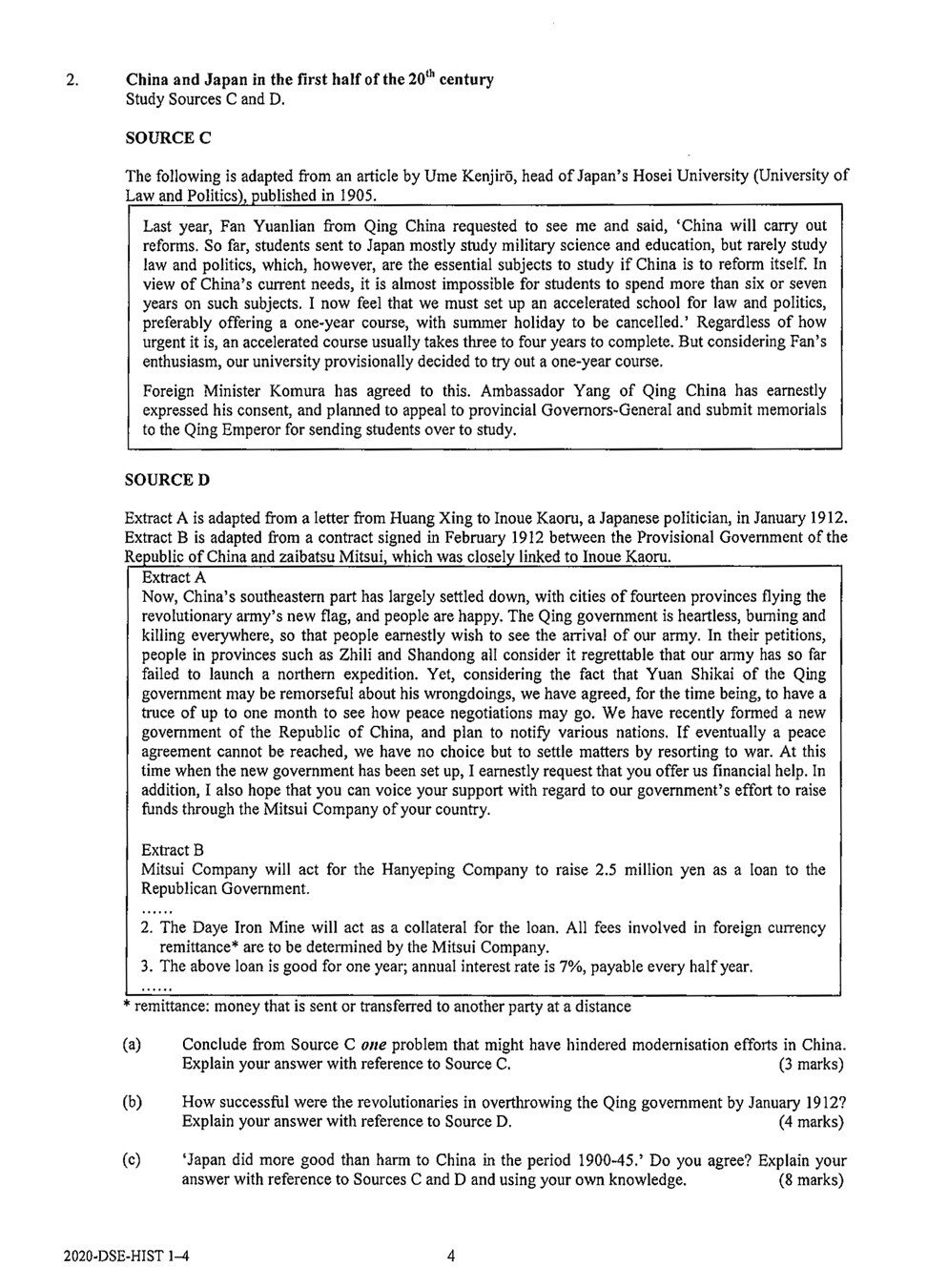

DSE history candidates sat their exam on Thursday morning. One question titled “China and Japan in the first half of the 20th century” required students to read two texts and use their own knowledge to answer.

The first text was an article written in 1905 by Ume Kenjiro, a former head of Hosei University in Tokyo, describing plans to welcome Chinese students to Japan to study law and politics, to bring about reform during the Qing dynasty.

The second contained extracts of a letter written in 1912 by revolutionary leader Huang Xing, seeking financial help from Inoue Kaoru, an influential Japanese politician. This reading also included excerpts of a contract, under which conglomerate Mitsui promised support to revolutionary leader Sun Yat-sen’s provisional government of the Republic of China.

Exam candidates then had to answer this question: “‘Japan did more good than harm to China in the period 1900-45.’ Do you agree? Explain your answer with reference to [the two readings] and using your own knowledge.”

How did the controversy play out?

Hong Kong’s pro-establishment politicians and teachers were the first to pounce after the exam, saying the question was biased and disregarded the horrors of the Japanese invasion of China.

At 9pm on Thursday, the Chinese foreign ministry’s office in Hong Kong wrote a Facebook post supporting those views.

Storm over Hong Kong history exam question just the tip of the iceberg

An hour later, the Education Bureau issued a rare, strongly worded statement condemning the way the question was framed. It said the question led candidates to a biased conclusion that would “seriously hurt the feelings and dignity of the Chinese people who suffered great pain during the Japanese invasion of China”.

On Friday, Secretary for Education Kevin Yeung Yun-hung demanded that the Hong Kong Examinations and Assessment Authority invalidate the question. He said there was “no room for discussion” because what Japan did to China in the first half of the 20th century, during which millions died, was “all harm and no good”.

The authority, which sets exam questions, promised to investigate.

Could anything else have triggered the furore?

A day before the exam, two pro-Beijing media outlets reported that two authority employees had made anti-mainland comments in social media posts meant for their friends only.

One was a member of the committee drawing up the history exam, while the other worked on liberal studies, another controversial subject.

The reports referred to more than a dozen Facebook posts, some dating back to 2010.

One post from this year, written in Chinese, said: “If there was no Japanese occupation, would there be a new China? Have you forgotten your origin?” The comment referred to a news report that a man was arrested on the mainland for wearing a Japanese army uniform to his wedding.

Hong Kong exams body blasted over ‘biased’ Japanese history question

The reports suggested the post implied that the Japanese invasion of China helped pave the way for the Chinese Communist Party’s rise to power.

That Facebook post and the news report were cited by the foreign ministry in its comments about the history exam. Its post was headlined: “‘Japan did more good than harm to China in 1900-1945?’ Hong Kong’s education system cannot become a ‘chicken coop without a flap’!”

That “chicken coop” remark was a reference to recent comments by Hong Kong leader Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor, on problems in the city’s education sector that needed fixing.

How are DSE exam questions set?

There were incidents in which questions were taken out after a DSE exam, but it usually involved technical issues, such as a multiple-choice question with more than two correct answers, teachers whom the Post spoke to said.

The authority is an independent, self-financing statutory body established in 1977, and runs the DSE and other public exams.

According to its website, every subject has its own moderation committee which produces the exam papers and marking schemes. Members include university academics, secondary school teachers, curriculum officers and subject specialists.

After drafters set the questions, the committee will review, discuss and modify them, taking into account the level of difficulty, clarity and appropriateness of the language used, among various aspects. It also considers feedback from a subject committee and overseas reviewers.

The Education Bureau is not involved in setting exam questions at any stage.

How can a student score well for that question?

A history teacher of more than 10 years said he believed the question at the centre of the storm was framed in a manner that was within the curriculum guidelines. He thought the question set out to test whether students could present an argument for both sides.

“The student is supposed to cite the good from the information on one side, and use his own knowledge to fulfil the requirements to talk about the harm,” said the teacher, who preferred to remain anonymous. “If a student gives a lopsided answer, he will not get full marks.”

Another teacher said asking if a historical actor or event “did more good than harm” was a common device used for decades in the city’s history exams. By presenting a “thought-provoking” statement, examiners aimed to stimulate critical thinking in students, said the teacher, who also declined to be named.

She said any student who hoped to do well in answering the offending question on Japan and China could not merely present a one-sided answer, and would be expected to point out biases in supplied reading materials.

“A candidate would not score highly if he or she did not point out the limitations of the historical data which did not show the war crimes committed by Japan,” she said.

Has there been any political fallout?

Hong Kong opposition politicians have criticised the foreign ministry’s involvement in the controversy, saying it showed how little respect Beijing had for the city’s autonomy.

“It is more than obvious that education, and this one, small exam question, is our domestic issue. It is beyond the scope of the Office of the Commissioner of the Foreign Ministry,” Civic Party leader Alvin Yeung Ngok-kiu said.

Democratic Party lawmaker Helena Wong Pik-wan said the move sent a dangerous signal, and accused the Education Bureau of disrespecting the professionalism of teachers and interfering with academic freedom.

Additional reporting by Victor Ting

Help us understand what you are interested in so that we can improve SCMP and provide a better experience for you. We would like to invite you to take this five-minute survey on how you engage with SCMP and the news.