Will national security law force exodus of Hong Kong’s teachers, students over fears of shrinking academic freedom?

- Rise in number of teachers resigning and students pulling out of school to emigrate, survey shows, as concerns over new ‘red lines’ grow

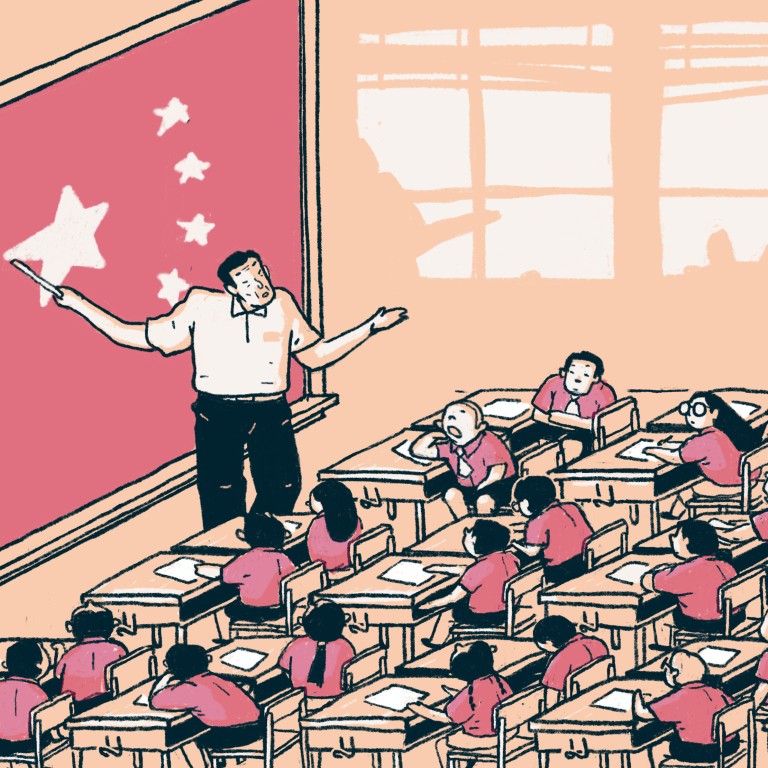

- Slew of directives to schools leaves some teachers worried about what they can and cannot teach now

Veteran primary school teacher Eva* will be leaving Hong Kong with her husband and child by summer to start a new life in Britain.

“My husband and I originally planned to send our child overseas while we continued working in Hong Kong, or maybe I would retire early and accompany our child there,” said Eva, whose child is in primary school.

She lamented that teachers now had limited autonomy in the classroom and that some educators were practising more self-censorship following guidelines issued by the authorities.

Schools and universities have been told to promote national security education among their students in keeping with the new law, which bans acts of subversion, secession, terrorism and collusion with foreign forces, and carries a maximum penalty of life imprisonment.

Eva, who was born and raised in Hong Kong, said many of her friends had been planning to leave over the past few months, and some had already gone, along with their families.

“There are so many uncertainties ahead … but I feel that I can always find another job,” said Eva, who is in her 40s and has taught general studies for more than 10 years.

“Many parents like us are more worried about what kind of education our children will receive in future,” she added.

Last month, education officials announced that liberal studies – a senior secondary subject that pro-Beijing politicians have blamed for radicalising youth – would be renamed “citizenship and social development”, with a new syllabus focusing on national security, identity, lawfulness and patriotism.

At the university level, fears that the national security law would lead to self-censorship and affect academic freedom had already come to pass, according to some students and teachers. Some institutions have begun looking into making national security a mandatory subject for all students.

In February, Chinese University effectively severed ties with its student union over concerns that its electoral platform possibly breached the national security law.

On Monday, Communist Party mouthpiece the People’s Daily lashed out at the University of Hong Kong’s student union following its criticisms of the security law, calling it “a malignant tumour” that should be removed. Earlier this month, local pro-Beijing media attacked Polytechnic University’s student union, accusing it of “beautifying” the 2019 protests by setting up street counters to promote an exhibition showcasing photographs from the months of social unrest.

School heads have until August to tell education authorities what they have done on national security education and describe future plans, which Eva described as a rushed campaign that had put more pressure on teachers and schools, while the guidelines themselves were overly strict.

“Many guidelines have been introduced abruptly, and there is simply no way for schools to get around them,” she said.

Guidelines from the bureau include inserting elements of national security education into various other subjects, such as Chinese language, general studies and civic education at the primary level, and biology, physics, history, geography and economics at the secondary level.

For example, the bureau said, older primary pupils could learn to appreciate the importance of national security by understanding campus security, as well as being taught about historical events and the geography of mainland China.

Despite all the advice from the bureau, Eva said many teachers were still uncertain about the boundaries resulting from the security law and what they should look out for.

“We wonder what can be taught and what is banned, and how far and deep we can go in approaching a topic,” she said. “We also don’t know what pupils will tell their parents about what they’ve learned at school. And what if some parents have strong political affiliations?”

She said at least 10 of her friends and colleagues were either planning to leave or have already emigrated with their families as of last month. Dozens of pupils have also withdrawn from her school over the past six months, including many who moved overseas.

A recent survey of 98 schools by the city’s biggest secondary school principals group found that the number of teachers who resigned to emigrate doubled last year compared to 2019.

At least 37 educators quit and emigrated between July and November last year, compared with 18 over the same period of 2019, according to the Hong Kong Association of the Heads of Secondary Schools. More than 723 secondary school students withdrew from the 98 schools to move overseas, a 52 per cent increase from 2019.

Secondary school principal Tony* said many schools had seen one or two teachers resigning in the middle of the school year – something that did not happen before.

“In the past, most teachers usually would not resign in such a hurry,” he said. “But now, many are leaving immediately, or after giving just one month’s notice.”

Taking care to avoid ‘red lines’

Some of the dozen teachers and school heads who spoke to the Post said they noticed increased scrutiny of school-based teaching materials this year.

But education minister Kevin Yeung Yun-hung this month dismissed teachers’ concerns about the security law, saying they “need not worry” as long as they “love the country”.

Asked if teachers could still tell their pupils about events such as the June 4 crackdown or discuss corruption in mainland China, he said teachers could use their professional judgment to decide.

In one of his blog posts, Yeung said the fact that many teachers and students were arrested during the 2019 protests showed the need to strengthen concepts pertaining to national identity in schools.

Official figures showed about 40 per cent of more than 10,000 people arrested were university or secondary school students, and more than 100 educators were detained.

In October 2019, at the peak of the protests, as many as 350 secondary school student concern groups were formed with the aim of pushing for greater democracy. But with the introduction of the national security law, many have dissolved or disbanded, fearing reprisals from authorities.

One of the most active groups, Ideologist, helped to organise at least two citywide class strikes along with other concern groups and urged their peers to stage campus protests.

Spokesman Carson Tsang Long-hin, a Form Six student, said members discussed last June whether the group should stop operating but voted to carry on.

“Even if we disbanded, the authorities could still arrest us if they wanted to,” said Tsang, 17. “Perhaps taking one step at a time and playing it by ear might be another way forward.”

The group has about 10 members, all senior secondary school students.

Tsang said the national security law had affected how they went about their activities now, as they had become cautious about crossing “red lines”.

“When writing social media posts, we are now more careful and check for any wordings that might violate the security law,” he said.

University staff, students more cautious too

Under the security law, universities also have to promote national security, although they have more leeway than primary and secondary schools and have not been issued specific guidelines by the authorities. The University of Hong Kong recently proposed forming a committee to probe alleged violations of academic freedom under the legislation, an idea one senior staff member described as “well intended”.

Undersecretary for Education Choi Yuk-lin said last month the authorities would look into whether university management staff would be required to take an oath and swear allegiance to the city, after government school teachers were required to do so.

Even before the institutions could roll out their plans, some have already noticed lecturers and students being more cautious in class.

Lingnan University visiting assistant professor of cultural studies Ip Iam-chong said he noticed that local students appeared to have become more reticent about expressing their views on political issues in Hong Kong.

“For example, last year when some mainland Chinese students were presenting about the 2019 protests … many local students were not really willing to respond, which felt weird as many of them had personally experienced the protests,” he said.

Ip added that the university’s management had not issued teaching staff any guidelines or advice so far about teaching under the national security law.

He said some of his colleagues had left Hong Kong in recent months and others were considering doing the same, worried about restricted academic autonomy under the law.

Polytechnic University student union president Alan Wu Wai-kuen, a Year One student, recalled that the teacher of a class he took on Chinese politics was cautious with topics considered sensitive on the mainland, such as the Tiananmen Square crackdown and the human rights activist and Nobel laureate Liu Xiaobo.

“He was discreet and reminded us that there were things which could be difficult to say publicly,” Wu recalled, adding that the lecturer touched on Tiananmen Square only briefly, although it was part of the course’s lecture notes.

Hong Kong has already slipped significantly in a global ranking of academic freedom in universities for last year.

Last month, the Germany-based Global Public Policy Institute’s latest index of academic freedom gave Hong Kong a score of 0.348 out of 1 (one) – down from 0.442 in 2019. This was lower than the score for Singapore, Russia and Cambodia.

Scholars at Risk, a US-based network of more than 500 institutions in 40 countries that contributed to the report, cited the arrest of academics and students under the security law among concerns about the pressures on the higher education community in research and international collaboration.

Those arrested include legal scholar Benny Tai Yiu-ting, as well as university lecturer and former opposition lawmaker Claudia Mo Man-ching.

Fung Wai-wah, president of the 100,000-strong Professional Teachers’ Union, said he was concerned about the ongoing impact of the national security law on teachers and students.

Not only might more of them emigrate, but fewer young people might be drawn to the education sector given the increasing restrictions and fears of “white terror”, he said.

But Wong Kam-leung, chairman of the 40,000-member Federation of Education Workers and a primary school principal, disagreed, saying Hong Kong needed to plug the gap in safeguarding national security for the good of the country.

“Teachers and schools, like others, have the responsibility to promote national security education,” he said.

“Even though some parents may feel unnecessary fear and choose to emigrate, Hong Kong’s development is definitely going in a positive direction … Some of them might even come back.”

Secondary school student and concern group leader Carson Tsang said he was among those who had no plans to leave Hong Kong, even though the future seemed gloomier now.

“Many people have been put in prison for what we were fighting for [in 2019], while others had been on remand, prosecuted or fled overseas,” he said.

“If I choose to emigrate at this stage only because of the negative mood, I would feel guilty. I would not want to give up at this stage.”

*Names changed at the interviewees’ request