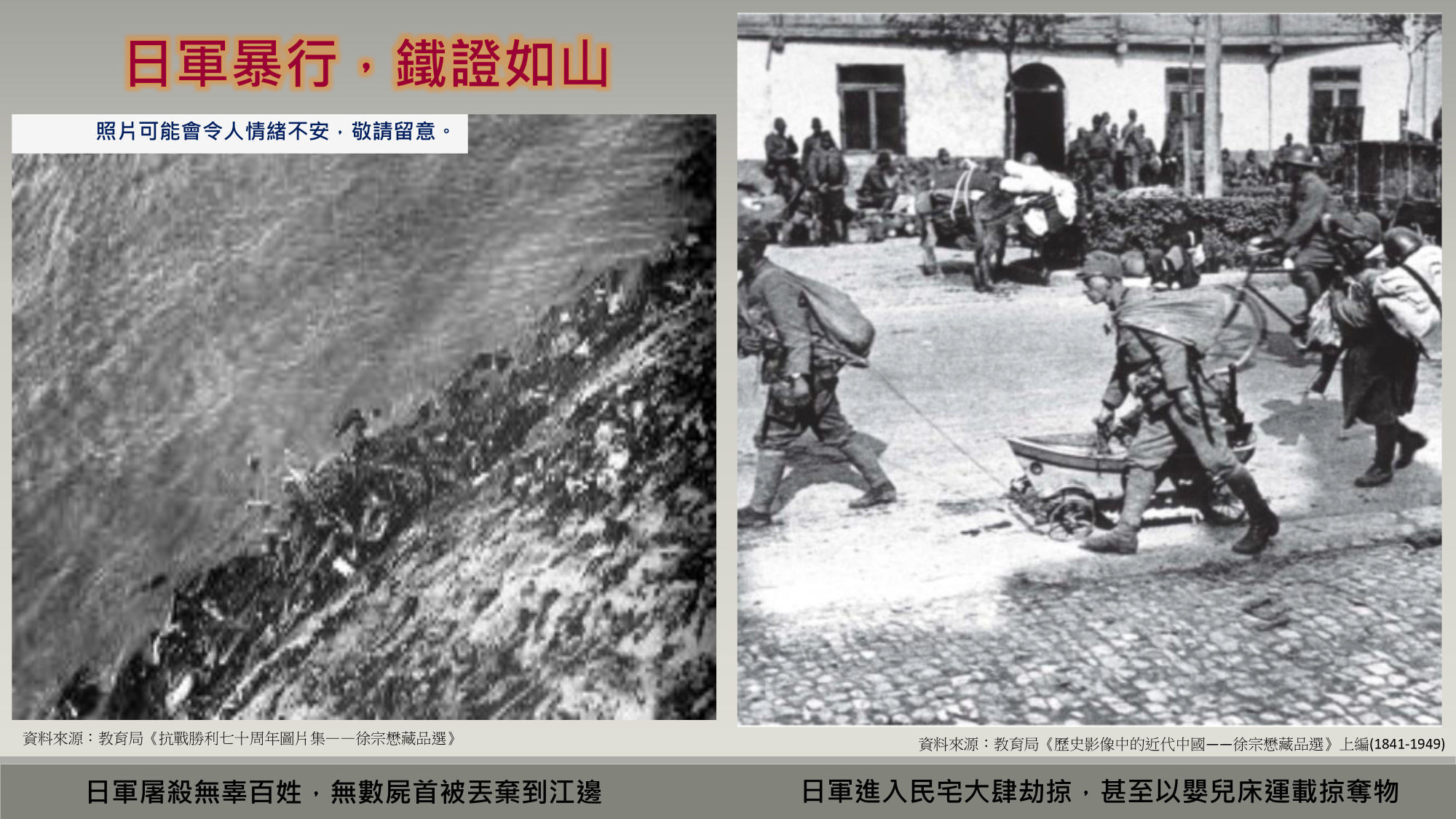

Use professional judgment to vet lesson materials, Education Bureau tells teachers after graphic Nanking massacre footage backed by authorities shown to Hong Kong pupils

- Video used as part of commemoration event included footage of Japanese soldiers burying civilians alive and shooting others in the head

- The PLK HKTA Yuen Yuen Primary School tells parents it will make adjustments to teaching materials according to different grades

Education authorities have stressed that teachers must use their professional judgment when deciding whether to use government-supplied learning materials after primary school pupils in Hong Kong reported feeling distraught over graphic footage of the Nanking massacre shown in the classroom.

The children, some as young as seven according to sources, watched video endorsed by the Education Bureau that included scenes of rampaging Japanese soldiers burying Chinese civilians alive and shooting them in the head, as well as fields littered with the dead, including the bodies of babies.

PLK HKTA Yuen Yuen Primary School in Tuen Mun showed the footage to the pupils, some of whom the insiders said were in Primary Two, last Thursday as part of its activities commemorating the massacre by the invading Imperial Japanese Army, which began on December 13, 1937, in the city now known as Nanjing.

China estimates that more than 300,000 people died before the slaughter ended about six weeks later.

The school sent a statement to parents on Saturday saying it was “distressed and worried” to learn that some children felt uneasy after the class.

“Our school will pay more attention to the children’s feelings in the future, and make appropriate adjustments to the teaching materials according to different grades,” it said. “We know that national education is vital; however, we should put children’s feelings into our consideration.”

In a reply sent to the Post by the school and Po Leung Kuk, a charity that runs the institution, a spokesman said they were very concerned some pupils were disturbed by the teaching materials provided by the bureau.

“The school will pay more attention in the future, so students’ emotions and feelings will be better taken care of while they learn about the historical events,” he said.

It vowed to offer counselling to pupils and urged parents to alert teachers if their children expressed worrying feelings over the incident.

The commemoration was part of the school’s drive to follow the bureau’s call for educators to develop in students “a sense of national identity and a sense of commitment towards the nation”.

One video was produced by public broadcaster RTHK and the other by the state-run Xinhua News Agency.

In addressing the controversy, the bureau on Sunday pointed out that the video in question had already been broadcast on local television and uploaded to the internet, making it information anyone could consume.

“School staff can choose the documentary or other materials to teach the Nanking massacre, and when using videos or images of the war, teachers should use their professional judgment and guide students adequately,” it said.

The materials, which contained links to the footage, included warnings about graphic content.

The authorities further added that teaching students about the history of the Sino-Japanese war was a “meaningful exercise” and “history is history, it cannot be avoided”.

Oldest survivor of Nanking massacre dies at 100

The bureau said it hoped society could understand that teaching national history was an important part of educating the next generation, and residents should trust in teachers’ professionalism and guidance and avoid being misled by “one-sided opinions”.

PLK HKTA Yuen Yuen Primary School would still observe a one-minute moment of silence to commemorate the Nanking victims on Monday and hold a special class to “ease the children’s emotions and teach them different ways to face difficulties”.

Other schools have issued circulars to parents seeking to reassure them over lessons about the event. WF Joseph Lee Primary School in Tin Shui Wai informed parents on Saturday it would not show the footage provided by the government, which it said was more suitable to secondary school students.

Ng Wing-hung, principal of Buddhist Lim Kim Tian Memorial Primary School in Kwai Chung, said management reached the same conclusion after reviewing the two videos.

“A thorough debriefing must be conducted with the students if these clips are shown, but we just do not have enough time,” he said.

China holds low-key Nanking massacre memorial service as it seeks better ties with Japan

“We have to be extremely sensitive when handling the issue as children may have different reactions to it. Some may not show immediate distress in class but only later at night when they sleep. It will be very undesirable if we cannot address their emotions in a timely manner.”

Ng said his school would only brief its pupils about the incident during the morning assembly on Monday and observe the moment of silence.

Polly Chan Shuk-yee, principal at Yaumati Catholic Primary School (Hoi Wang Road), said her school would adopt a similar approach.

“We found the footage too bloody and violent and that it may scare our children,” she said, adding teachers would show only pictures depicting general scenes, such as destroyed houses.

Schools had a responsibility to screen teaching materials provided by the bureau, which were not compulsory, based on their circumstances and the maturity of the pupils, she added.

In a circular issued to all primary and secondary schools in mid-November, the bureau said it had designed a commemorative activity plan, which included playing the national anthem and showing the two clips followed by a student sharing session.

It encouraged schools to organise related activities during weekly assemblies or add them to lessons on moral and civic education, previously known as liberal studies. Teachers could take their “own contexts and needs” into consideration when using the resource kit.