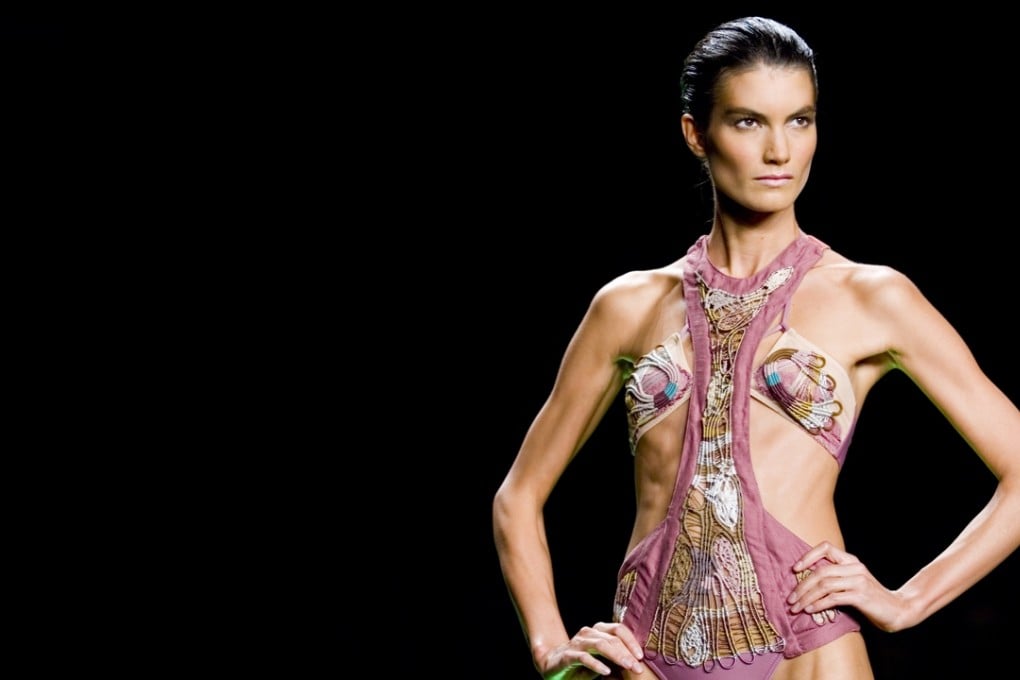

Scientists want too-thin models off catwalks; toddlers handy with touch screens

Medical experts say US government should follow France and stop dangerously thin models exerting a bad influence on the young and impressionable

Prohibiting catwalk models from participating in fashion shows or photo shoots if they are dangerously thin would go a long way towards preventing serious health problems – including anorexia nervosa and death from starvation – among young women, according to experts from Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

In an editorial published online in the American Journal of Public Health, the experts called for the US Occupational Safety and Health Administration to set regulations that would prohibit the hiring of models below a given body mass index (for example, a BMI under 18). The authors noted that the average catwalk model’s BMI is typically below the World Health Organisation’s threshold for medically dangerous thinness for adults; that is, under 16. BMI is calculated by taking the square of a person’s height in metres divided by their weight in kilograms. This month, the French National Assembly passed a law that bans the hiring of excessively thin models. The Harvard experts said if the US joins France in regulating the hiring of dangerously thin models, it “would shake the fashion industry, even if enforcement dollars were few and far between. Designers would be hard pressed to maintain a presence in the industry without participating in the New York and Paris fashion weeks.”

Two-year-olds are adept at using touch screens, and can swipe, unlock, and actively search for features on smartphones and tablets, a study published online in the Archives of Disease in Childhood shows. The findings were based on 82 questionnaires on touch screen access and use, completed by the parents of children aged between 12 months and three years. Most of the parents (82 per cent) said they owned a touch screen device such as a smartphone or tablet. Of these, most (87 per cent) gave their child the device to play with for an average of 15 minutes a day, and nearly two-thirds said they had downloaded apps for their child to use. Nine out of 10 parents who owned a touch screen device said their child was able to swipe; half said their child was able to unlock the screen, and nearly two-thirds felt their child actively searched for touch screen features. The average age of the toddlers with the ability to perform these three skills was 24 months. “Interactive touch screen applications offer a level of engagement not previously experienced with other forms of media and are more akin to traditional play,” the researchers write. “This opens up the potential application of these devices for both assessment of development and early intervention in high-risk children.” Nevertheless, they caution: “Many applications designed for infants and toddlers already exist, but there is no regulation of their quality, educational value, or safety. Some of the issues that arise with passive watching of television still apply.”

A study has found that young children who have sustained sports-related concussions have impaired brain function two years after the injury relative to their peers who do not have a history of mild traumatic brain injury. Published in the International Journal of Psychophysiology, the study by the University of Illinois included 30 eight- to 10-year-old children who are active in athletic activities. Fifteen of the children were recruited two years after a sports-related concussion and the remaining children had no history of concussion. The researchers assessed the children’s ability to update and maintain memory, as well as pay attention and inhibit responses when instructed to do so. The team also analysed electrical signals in the brain while the children performed some of these cognitive tests. With the brain signals, they were able to measure how each child’s brain performed the tests. Relative to children in the control group, those with a history of concussion performed worse on tests of working memory, attention and impulse control. This impaired performance was also reflected in differences in the electric signals in the injured children’s brains. Also, among the children with a history of concussion, those who were injured earlier in life had the largest deficits.