Hong Kong’s lack of rehabilitation services leave minority drug addicts with nowhere to turn

Language, religious and cultural barriers prevent many Nepalese drug addicts in the city from getting the vital help they need

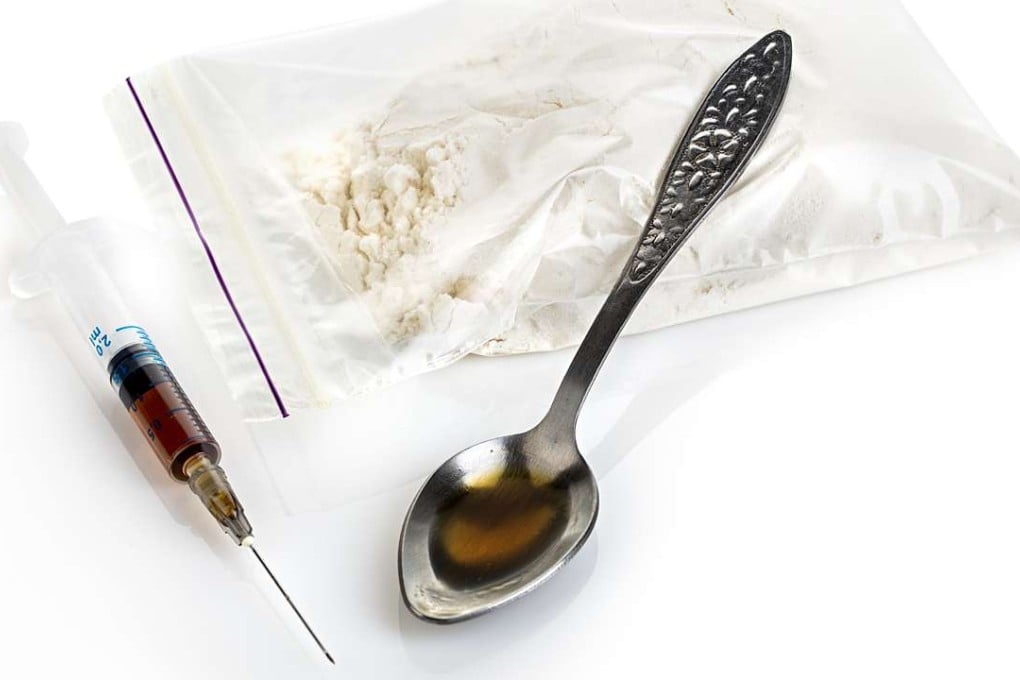

Thapa was only 16 when he first started abusing ‘brown sugar’ - an adulterated form of heroin - in Nepal.

He came to Hong Kong in 2004 to reunite with family, but pressured by peers and feeling disenfranchised by his experience as a member of an ethnic minority in the city, Thapa turned to heroin. He was only 18.

“Before, I had no meaning to my life,” he said.

Thapa’s story is not unique in the Nepalese community. Drug abuse among ethnic minorities in the city has been on the rise since 2005.

Statistics show drug use has risen from 1.4 per cent to 3.6 per cent in the Nepalese community, compared to a rise from 0.4 per cent for other South Asians to 2.6 per cent in this year’s first quarter.

“We and the government also know there is under reporting,” Andy Ng Wang-Tsang, chief executive at the Society for Rehabilitation and Crime Services, said. The Nepalese community has the worst problem, making up 42.8 per cent of ethnic minority drug addicts, according to a Chinese University study in 2014.