Hong Kong and mainland China have cooperated on healthcare – but new partnership is no instant cure

The road to reunification between Hong Kong and mainland China has been a bumpy one over the past 20 years and their relationship has, if anything, become even more sensitive in recent years. In the first of a three-part series that also looks at education and marriage and retirement options, here we ask it realistic to open up the mainland health care market and to bring it closer to international standards?

Tension between Hong Kong and the mainland was high in 2003 after the deadly outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (Sars).

An infected professor, who worked at a Guangzhou hospital, spread the respiratory virus to guests at the Kowloon hotel where he was staying and on to medical staff who treated him.

Hospitals, doctors and nurses were among the first to suffer in an epidemic that infected 1,755 and claimed 299 lives in the city.

As health control measures were tightened at the border to prevent further spread, mainland officials were accused of a Sars cover-up.

Many Hongkongers still remember the darkest of days as they travelled on public transport fearful of those wearing face masks around them in a panic-gripped city that many had abandoned.

They forged greater ties, established disease surveillance systems, improved prevention measures, and conducted scientific research.

In the wake of its hard-won Sars battle, Hong Kong extended its influence to global health care issues. With the backing of Beijing, former director of health Dr Margaret Chan Fung Fu-chun rose to lead the World Health Organisation in 2006, a post she holds to this day. Through greater integration, many hope its example will lead to the reform of the mainland medical system.

Others believe that the city has a lot to offer the mainland in terms of skills, advanced technology, management and investment opportunities.

Only a few practitioners trained in Hong Kong have taken the opportunity to operate across the border. The blame for this has been laid on everything from complicated licence procedures, lack of legal guarantees and the tax system, to the culture of doctor and patient relationships.

In 2015, 29 certificates were issued to Hong Kong operators under Cepa to run health care businesses on the mainland. Of those, only 26 still operate.

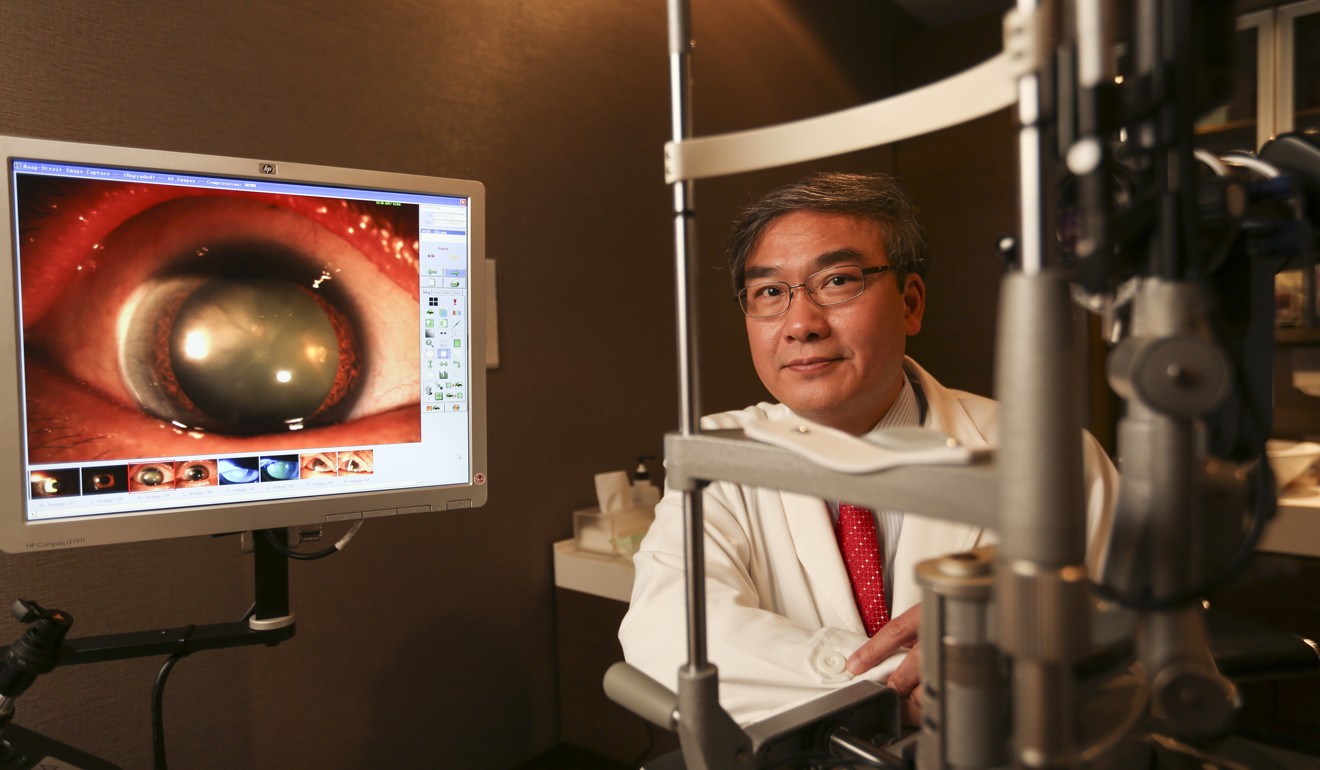

Dr Dennis Lam Shun-chiu, who opened the first wholly Hong Kong-owned hospital in Shenzhen in 2013, hopes his success may inspire others.

“For Hong Kong doctors, it’s a good time to join the mainland market now. Do not wait until later,” said Lam, adding they enjoy the advantages of Cepa as well as a good reputation with patients.

“Medical capital is very hot and many investors are eyeing the China market, but they do not have the advantages of Hong Kong professionals,” he says.

“If Hong Kong doctors do not make a head start, such an advantage will be lost after a few years when all the overseas capital floods in.”

Under Cepa, Hong Kong health care providers are allowed to set up medical institutions, including outpatient clinics, in the form of wholly owned, joint equity or contractual joint ventures.

Locally registered medical practitioners may provide short-term services for up to three years under a renewable licence without requiring mainland qualifications.

Mainland hospitals do not welcome Hong Kong doctors too, as they see them as competitors

“We are looking into these developments very closely as they are exciting news. Once Hong Kong’s high-speed raillink is in service, geographic barriers will be cleared. Hong Kong doctors may travel to these areas in less than an hour, and patients from all over the country can flood in to see them.”

In April, New Frontier, a diversified holding company led by former Hong Kong finance minister Antony Leung Kam-chung, announced a 1 billion yuan (HK$1.13 billion) investment in a Shenzhen-based medical group as a pioneering move to participate in the Greater Bay Area.

University of Hong Kong liver transplant expert Professor Lo Chung-mau, who has headed the university’s financially troubled hospital in Shenzhen since 2016, says Hong Kong doctors have a role in helping build a better mainland medical system.

By introducing price reform to provide a fixed package rate for common procedures, Lo hopes his hospital can help build patient confidence towards the service provider and influence other mainland hospitals to increase transparency in terms of medical fees.

But Medical Association president Gabriel Choi Kin, says the mainland is not attractive to most local doctors.

“The medical cultures are too different,” he says, with Hong Kong doctors having to go through various complicated procedures before being able to set up a clinic or hospital. “For one thing, how can you ask Hong Kong doctors to write medical records and all the drug names in Chinese?”

“To start a career in the mainland, doctors either have to go through the traffic every day, or move their entire families and raise their children there. How attractive can that be?”

Choi said Hong Kong doctors have to go through complicated procedures at various departments before being able to set up a clinic or hospital.

These include submitting an environmental impact assessment and gaining the approval of those living nearby.

In Hong Kong, a graduate in medicine is free to open a clinic as long as they have passed the licensing examination.

“Mainland hospitals do not welcome Hong Kong doctors too, as they see them as competitors,” Choi added.

While Hong Kong doctors are holding back, those from the mainland are increasingly interested in seeking a career here, even though the chances of them passing the local exam are relatively slim.

Some 809 students trained on the mainland sat city licensing tests between 2011 to 2015, but only 86 passed.

Debates have also broken out recently over whether more overseas or mainland doctors should be allowed to work in the city. On the one hand, public hospitals say they are short of about 250 practitioners while, on the other, local doctors question the qualifications of counterparts, especially those mainland trained.

As such, the role Hong Kong and mainland doctors play in each other’s health care system remains debatable in the sector. But the cross-border situation is more settled in the eyes of researchers.

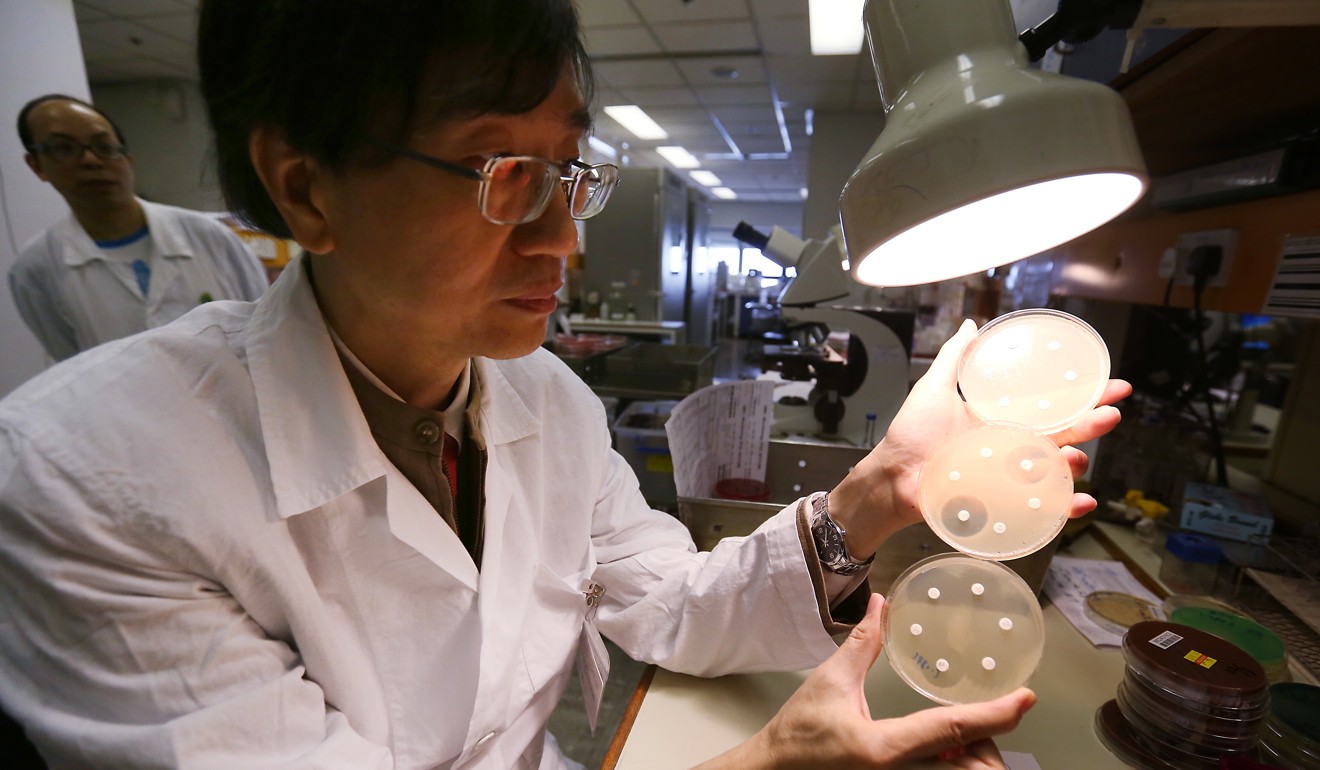

However Professor Yuen Kwok-yung, head of the HKU department of microbiology, says there is now greater cooperation between the city and the mainland in research and scientific studies.

“There are many conjoint studies in basic science and medicine,” Yuen said. “[There are more opportunities for Hong Kong researchers] in terms of exchanging research ideas, collaboration and funding.”

But he also pointed out there was much work for the Hong Kong government to do in order to retain medical excellence in the city.

“Hong Kong research is advanced in general but we are still very much behind many developed places because the amount of GDP invested in public hospitals is much lower. Moreover, areas such as the control of antimicrobial resistance and infection are also very backward when compared with places like Britain and Europe.”

He believes it is up to Hong Kong to increase its ties with the mainland as well as the international community. “Just go where there is excellence,” Yuen says.