Doctors deny condition critical at Hong Kong’s public hospitals despite complaints and creaking system

Blunders have shaken faith in Hong Kong’s public health care, but doctors say errors are few despite overcrowded hospitals, staff shortages and disgruntled patients

Hong Kong wept for Tang Kwai-sze when her teenage daughter was left begging for a liver donation to save her mother’s life in April. The dying woman was in desperate need of a transplant and her 17-year-old daughter was ready to give it to her, but was denied the right to do so by virtue of being just months shy of the legal age of consent.

Their appeal hit headlines and drew an outpouring of sympathy, but those emotions turned to anger weeks later when it emerged that Tang’s predicament was a result of negligence by two public doctors at United Christian Hospital in Kwun Tong.

The doctors had failed to prescribe Tang a precautionary antiviral drug in conjunction with a high dose of steroids she had been given for a kidney condition. The absence of the medicine exposed her to the risk of liver failure.

Tang continues to fight for her life at Queen Mary Hospital in Pok Fu Lam after undergoing two separate transplants, one from a stranger and another from a deceased patient. The extent of the damage done to both her and the reputation of Hong Kong’s public doctors remains unclear.

The episode was one of a number of high-profile blunders in recent months that shed light on chronic problems in the overburdened public health care system, as it grapples with rising demand amid a rapidly ageing population.

Manpower shortages, the increased complexity of many illnesses, unclear protocols on drug prescriptions, complex new technology for patient records, and a failure of reporting systems for blunders all appear to have taken a toll on patient care. However, statistics and doctors paint a very different picture, arguing that the number of incidents has actually been in decline, and that the real problems lie elsewhere.

Despite its challenges, Hong Kong’s health care system has been lauded as one of the world’s best after achieving enviable results in promoting public health.

According to data company Bloomberg’s Health Care Efficiency Index ranking for 2014, the city was the second most efficient place for health care in that year, second only to Singapore.

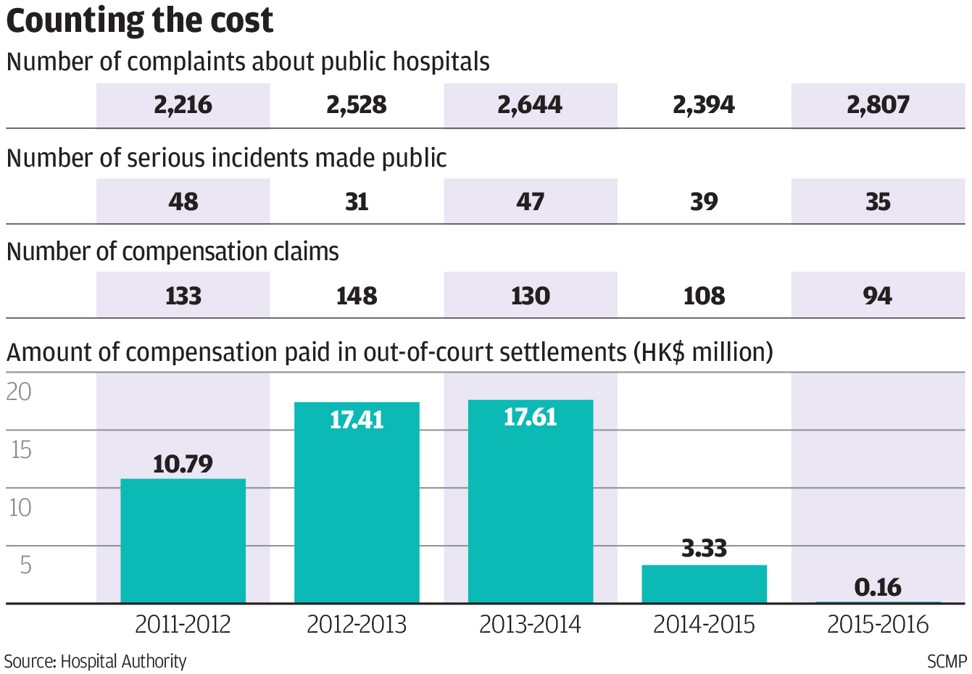

Figures from Hong Kong’s Hospital Authority show the number of serious medical blunders reported in the past five years declined slightly, despite a rising number of disgruntled patients.

A total of 12,589 complaints were received by public hospitals in the period, while the annual number rose steadily from 2,216 in 2011 to 2,807 last year.

In 2012, there were 48 blunders classified as serious, the highest number in the past five years. The figure lingered at between 31 and 47 over the five years, ending on 35 cases in 2016.

The mishaps were equivalent to a rate of around two incidents per one million patient appointments – about 10 times lower than the figure of 23 in the Australian state of Victoria, where a similar reporting system to Hong Kong’s is in place for mistakes.

“The number of medical blunders has actually been declining in recent years, and the incidence rate is rather low compared with other affluent cities,” said Dr Kwok Ka-ki, a doctor and member of Hong Kong’s legislature.

“Of course, one medical blunder is already too much to tolerate. But in reality, it is simply not possible to slash the number of mistakes to zero.”

Dr Seamus Siu Yuk-leung, vice-chairman of the Frontline Doctors’ Union, agreed.

“In fact, there are always many more compliments from the public praising hospital services compared with the number of complaints,” Siu said.

Recent reports about mishaps had damaged patient-doctor relationships and dampened the morale of doctors already overloaded with work in the understaffed public sector, he said.

“The morale is quite low, especially among those working in busy districts with high demand, such as Kowloon East.”

Both doctors said that legitimate medical complications in the course of an illness were increasingly being confused with human mistakes, possibly due to sensationalism regarding such incidents in the media.

Former Hong Kong Secretary for Food and Health Dr Ko Wing-man, also a doctor, said he had noticed that trend, too. Before stepping down from office on July 1, he said it was important to educate people to understand that not all incidents could be attributed to human error.

Dr Alfred Wong Yum-hong, from doctors’ group Médecins Inspirés, said: “Some of the serious incidents reported by the media as blunders were in fact known complications. There are always risks when carrying out health procedures, no matter how skilful doctors are. It is not fair to blame doctors for making mistakes in these situations.”

The doctors said the workload of frontline practitioners at public hospitals was huge, and physicians sometimes only had a few minutes to see a patient.

This manpower shortage shows no sign of being resolved anytime soon.

Government projections suggest the current shortfall of about 285 doctors will further rise to 1,007 by 2030, even if the sector employs all 450 students graduating each year from medical school.

Compounding the problem is the fact those projections are based on maintaining the current level of service – a standard which has seen patients in busy disciplines such as mental health wait up to three years for treatment.

The ratio of health care professionals to the city’s population stands at one for every 534 residents, according to 2015 figures from the Department of Health. There were 13,725 registered doctors in the city that year. The number of doctors per 1,000 residents was 1.9, the lowest among affluent cities. It was 2.3 in Japan, 2.6 in South Korea and 3 in Singapore.

There is also a widespread shortage of nurses, dentists and personnel in six other categories.

Officials have offered a basket of measures to alleviate the problem, such as increasing public and privately-funded training places, retaining existing manpower, asking retired veterans to work longer, and recruiting overseas talent.

But the government admits none of these offer an immediate solution, especially importing foreign doctors, which could be a quick fix but faces opposition from practitioners who fear their livelihoods might be threatened.

As hospitals feel the strain, officials are increasingly emphasising the importance of family clinics as the first port of call for patients.

Dr Donald Li Kwok-tung, president of the World Organisation of Family Doctors and a former president of the Hong Kong Academy of Medicine, said general practitioners were key to taking the pressure off public hospitals.

“Family doctors have an important role to play in providing regular care for patients, such as monitoring blood pressure and preventing complications,” Li said.

“By handling these daily situations well, they can improve the health of the elderly and at the same time lower the chance of patients needing emergency wards and taking up hospital beds.”

In reality, it is simply not possible to slash the number of mistakes to zero

Dr Lam Ching-choi, chief executive of Haven Of Hope Hospital, said family clinics and good palliative care were critical to managing demand. For example, giving patients the choice to die outside of a hospital would ease stress on these facilities, Lam said.

“Every patient in serious condition goes back and forth to hospital at least four or five times. If the legal framework could be relaxed to allow patients to die at home, it would give them a choice and at the same time lower the admission rate,” said Lam, who is also chairman of the government’s Elderly Commission and a non-official member of the Executive Council, which advises Hong Kong’s leader on policy.

Advances in technology can also help minimise the scope for mistakes, doctors say.

In Tang’s ordeal, an investigation by authorities found her medical history of hepatitis B was clearly stated in her medical records, and an electronic system had flagged to doctors the risk involved in prescribing her a high dose of steroids without the precautionary drug.

The head of the hospital said that normally there was an automatic pop-up window in the system warning doctors of the hazard.

But frontline doctors who actually use the system pointed out that the warning did not always turn up, and there were too many alerts in the system that sometimes distracted from the important ones, especially since physicians often only had a few minutes to see each patient.

Another system that has come under scrutiny is that for reporting blunders. Kwok said it needed to be enhanced to increase credibility and restore public trust.

The mechanism, adopted in 2007, says all public hospitals must report such events to their head office within 24 hours.

But following Tang’s shocking episode it was revealed that United Christian had failed to stick to the reporting protocol.

Kwun Tong Hospital noticed the mistake but kept Tang’s family in the dark until her daughter Michelle demanded an explanation weeks later on April 19.

United Christian did not report the incident to authorities until weeks later and only made it public more than two months after it took place.

Former minister Ko admitted United Christian had delayed reporting the blunder, and also disclosed that only 80 per cent of mishaps in public hospitals were reported in the 24 hours stipulated.

The remaining cases could not be filed within the time because they were too complicated and the hospitals needed more time to gather information from staff, patients and families, he said.

In July, an independent panel formed to review the reporting system after Tang’s incident suggested the Hospital Authority clarify and update the definition of a serious event requiring a report within the time frame, enhance the skills of health care executives in prompt public disclosure, and increase the frequency of publishing relevant statistics.

But the Hong Kong Patients’ Rights Association said a punishment system should be established for hospitals that failed to report incidents in good time.

“The authorities should also increase transparency on how staff are penalised to increase the credibility of public hospitals,” spokesman Tim Pang Hung-cheong said.

In a nod to public pressure, Hong Kong’s Food and Health Bureau is set to unveil a plan to reform the Medical Council, a doctors’ watchdog, in the hope of speeding up the process for public complaints and disciplinary hearings against doctors.

The council, which has the power to withhold licences to practise from doctors, has long been called a closed shop and criticised for the speed at which it disciplines doctors. It receives more than 500 complaints a year and takes six years on average to hold a hearing after receipt of a complaint.

“The target of this reform is to speed up the wait for a hearing against doctors and build up patient confidence in the health care sector,” according to a source from the bureau. The hope was that the majority of cases requiring an inquiry would be dealt with inside two years, the source said.