Elderly Hongkongers are way more likely to kill themselves than others. Why?

Social work expert says people underestimate the scale of the problem, thinking that abnormal behaviour and sadness are just parts of ageing. Therefore, many elderly do not get help with their feelings

Long life may be seen as a blessing, but those in what ought to be their golden years could feel otherwise, with elderly men and women in Hong Kong falling victim to depression, and taking their own lives at a much higher rate than their juniors.

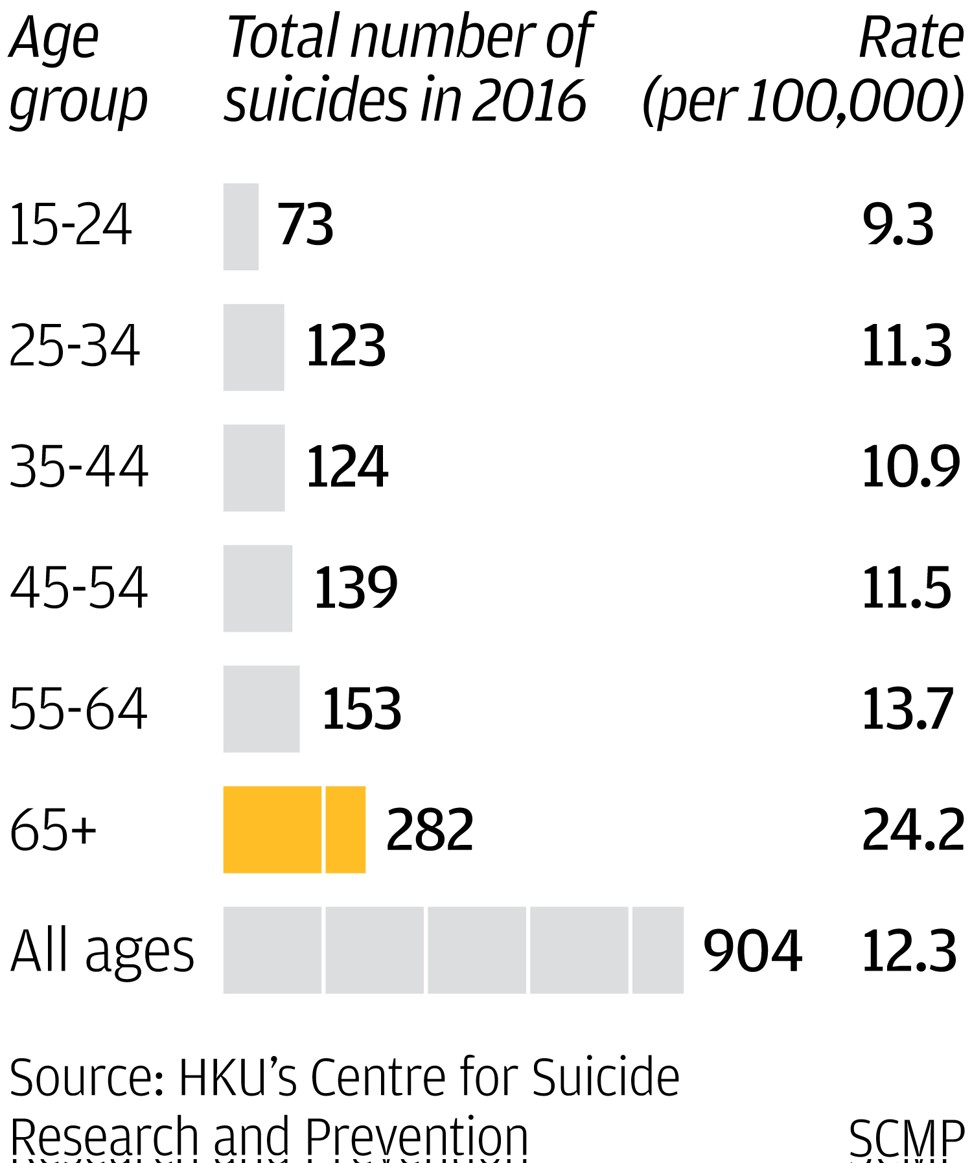

In 2016, 282 over-65s killed themselves in the city. And while officials and residents are increasingly cognisant of the local problem of student suicides, the issue of elderly suicides is largely unacknowledged.

Most times, it takes a suicide attempt for family members to realise that seniors are grappling with emotional issues which require counselling. And social work expert Terry Lum Yat-sang warns that Hongkongers could be missing telltale early signs.

“There’s an assumption in society that if older people are acting strangely, it’s probably because of dementia,” said the University of Hong Kong professor, who heads its department of social work.

“People will generally associate ageing with negative images such as downheartedness, solitude and hopelessness, all of which would easily normalise the phenomenon of elderly depression.”

But he says the signs can be spotted.

“There are usually signs of depression before elderly people attempt suicide as they prepare to end their lives. They may write a will, give away some of their belongings or say that their life isn’t worth living any more,” he says. “If they are unattended, then the situation may easily spiral out of control.”

While psychological help is available, uptake among the elderly is low because of that common belief, that depression is a normal part of ageing.

The weak appreciation of the size of the problem stands in contrast with the attention which has in recent years been focused on the city’s tragic spate of student suicides.

Lum led a study on attitudes to elderly depression published last month, after researchers interviewed 1,322 residents aged 20 and above, finding that 687 – or 52 per cent – of them estimated that only 10 per cent of older people were depressed.

The suicide expert battling to turn a tragic tide in student deaths

“When seniors exhibit signs of the problem, families don’t see the need to take action or seek help because they don’t see it as a disease and have normalised the condition,” he says. “It’s incorrect to believe that elderly depression comes with old age. In fact it is an abnormal process of ageing and it needs to be addressed.”

The survey – conducted by the Jockey Club Joy Age, a three-year project aimed at supporting the mental wellness of the elderly – suggests the public has been approaching elderly depression the wrong way.

“Reminding [depressed seniors] of their blessings is not the best way to handle such patients and by doing so, they are ignoring their feelings, which will make them feel even worse. Not only do they feel isolated and unwanted, they also feel misunderstood and rejected,” Lum says.

The best way to really do so is to spend more time with them, do the activities they enjoy doing, whether it’s hiking or playing mahjong

This is among many factors that contribute to making older people feel vulnerable, heightening the risk of depression and stress, leading to health problems and social disengagement.

According to figures from HKU’s Centre for Suicide Research and Prevention, the suicide rate for people over 65 in the city stood at 24.2 per 100,000 people per year in 2016, and with the city’s rapidly ageing population the number of elderly people killing themselves is expected to rise in the coming decades.

That suicide rate for the elderly – despite having decreased from a 2003 spike of 40.4 – looms much higher than the rate for any other age group. The rate for the group aged 55 to 64 is second-highest at 13.7, with the groups aged 25-34, 35-44 and 45-44 all hovering around 11. The rate for the 15-24 group is 9.3, and the rate for Hongkongers of all ages is 12.3.

So what can be done to help this group clearly at a heightened risk of suicide?

Lum says: “Attention needs to be given especially to the changes in elderly people’s conditions and their complaints. The best way to really do so is to spend more time with them, do the activities they enjoy doing, whether it’s hiking or playing mahjong.”

Only visiting older relatives on special occasions like Lunar New Year will not do the trick, he adds, saying: “It’s important we keep regular contact with them. It can help to understand their daily lives and chat with them about their feelings, which will work well in preventing the possibility of depression as well as suicide.”

But treatment can be difficult in the community. That is why since October last year Joy Age has partnered with district elderly community centres or integrated home care services in four different Hong Kong districts to open integrated community centres for mental wellness, providing holistic support for older people at risk of depression.