Exclusive | His DNA test for Down’s Syndrome benefited millions but raised ethical dilemma about designer babies. Now Dr Dennis Lo predicts Hong Kong is ready for biotech boom

In a three-part series, the Post talks to winners of the InnoStars Awards, organised by Our Hong Kong Foundation to recognise leaders and promote innovation. In the first part, we sit down with Dr Dennis Lo, a pioneer in DNA testing

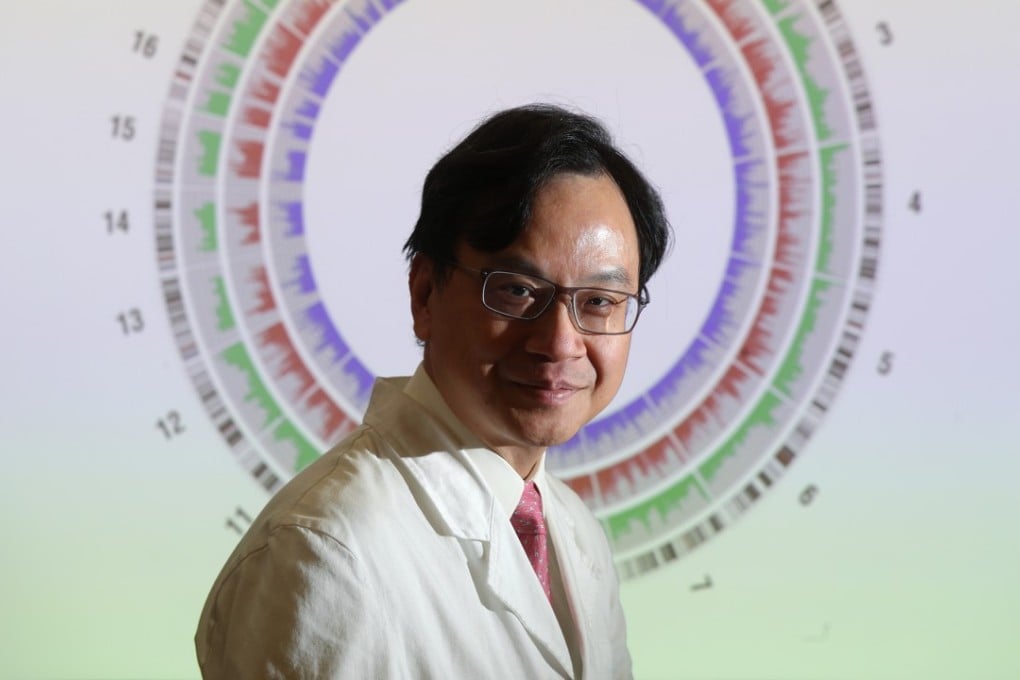

Dennis Lo Yuk-ming, 54, is one of Hong Kong’s foremost innovators in the realm of medical science. He was educated at Oxford University, the director of the Li Ka-shing Institute of Health Sciences and professor of medicine at Chinese University. He made a breakthrough discovery in DNA testing of pregnant women 30 years ago that led to the development of non-invasive testing for Down’s syndrome in the fetus. His discovery has benefited millions of women each year but raised an ethical dilemma about designer babies and DNA tests in our everyday lives. Lo, a winner of the Future Science Prize, considered the Chinese equivalent of the Nobel Prize, says the conditions are ripe for a biotech boom in the city.

What was your discovery about?

I was a PhD student in Oxford University and I had this idea around October 1996. Even before I was a medical student in Britain, I was thinking there might be some baby cells in the mother’s blood. So I was actually working on that from 1989 through 1997. In 1989, we found the number of fetal cells was very low. So it was difficult to do a reliable test.

In September 1996, I saw a couple of papers in a journal which said cancer cells would release DNA into the plasma of a patient. I realised a cancer growing in a patient was similar to a baby growing in the mother.

Are e-cigarettes all smoke and mirrors? One man’s quest for clean Hong Kong air

So I thought I could do something to look for fetal DNA in the mother’s plasma. I was about to move from Britain to Hong Kong and I didn’t have a lot of grants to do tests. So I could only do something cheap, but I had no idea how to get this DNA from plasma. I thought what if I cook it, just like cooking some noodles? I took a little bit of plasma and heated it for five minutes, and took a little of that juice to be tested. Strangely, even with that crude mixture, I was able to see a few DNA signals. For eight years, I had been looking at the wrong part of blood because I had thrown away that good bit, the plasma. I only looked at the cells.

What happened when you returned to Hong Kong?