Exclusive | Hidden pollution risk means Hong Kong’s typhoon signal No 1 might be scarier than you think

New findings suggest city’s standby signal coincides with spikes in amount of harmful pollutants making their way south from mainland China

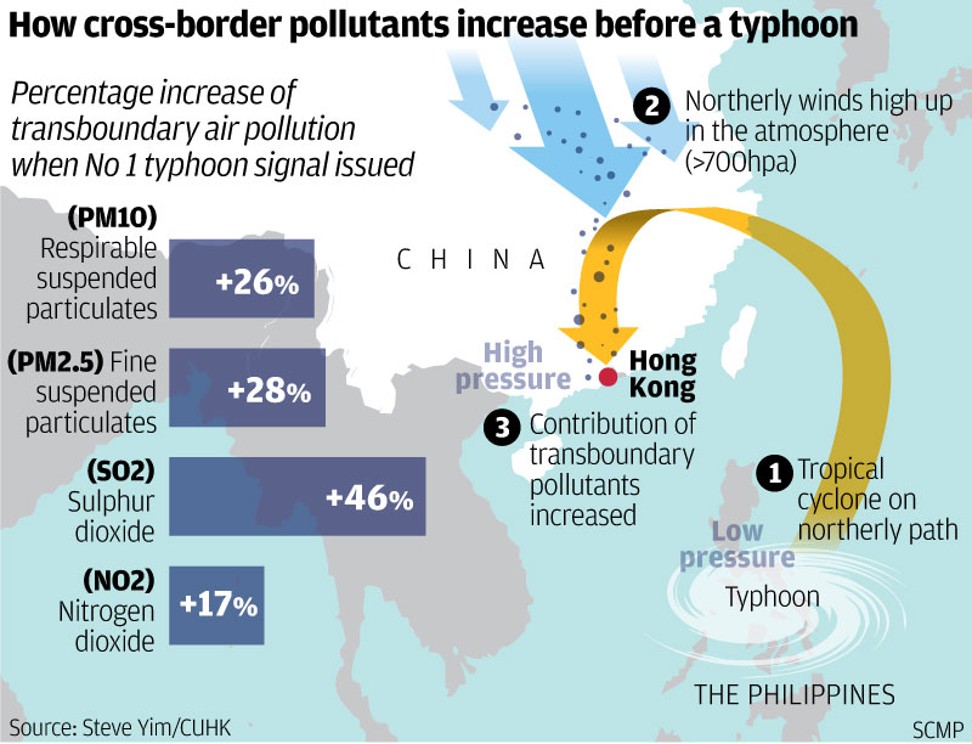

Storms given the lowest No 1 signal in Hong Kong’s warning system pose a much greater hazard than strong wind or rain in the form of harmful pollutants blown in from mainland China, a study has revealed.

Chinese University scientists found that an approaching typhoon could raise the inflow of pollutants by anywhere from 17 to 46 per cent, most of it fuelled by northerly air flows from across the border.

The team reached its conclusion after analysing more than 70 typhoons between 2002 and 2013. The results were replicated again for typhoons up to last year, with the same conclusions.

“We have found a substantial increase in transboundary pollution in Hong Kong whenever a No 1 typhoon [standby] signal is in effect,” co-author Steve Yim Hung-lam, assistant professor at the geography and resources management department, said.

The paper was published recently in the journal Science of the Total Environment.

Under the Observatory’s guidelines, a No 1 standby signal indicates that a tropical cyclone is about 800km from the city.

Measurements showed no major difference in local air pollution when a No 1 or No 3 signal was in place. Drops were even recorded when the No 3 or No 8 signals were in effect, due to heavy wind and rain helping to disperse pollutants.

“But No 1 signals are a bit freaky,” Yim said.

When a standby signal is in force, transboundary contributions of respirable and fine suspended particulates – PM10 and PM2.5 – sulphur dioxide (SO2), and nitrogen dioxide (NO2) go up by an average of 26, 28, 46, and 17 per cent respectively. All of those pollutants can harm the lungs and respiratory system.

This corresponded with a 6.4 per cent increase in the frequency of level seven readings on the 11-tier Air Quality Health Index (AQHI), denoting a “high” health risk.

“So when No 1 is in force, it’s often not the high winds that render it dangerous, but the pollution,” Yim said. “The government isn’t really communicating well but this is very important ... especially for outdoor workers.”

There were 12 No 1 signals in 2017, and there have been six so far this year. Earlier this month, a No 1 signal brought on by Severe Tropical Storm Bebinca lasted for more than 4½ days.

While it was previously believed that the high-pressure weather systems that preceded such storms caused the uptick in pollution from the north, Yim said “it alone could not fully explain the air pollution problem”.

His team discovered that the pollutants’ southerly migration was strengthened by strong northerly winds – of more than 700 hectopascals – blowing in the upper atmosphere, caused by the cyclone’s anticlockwise movement.

But there was a caveat. This phenomenon was only observed in typhoons that took a northerly track towards East Asia – which about 70 per cent of the studied typhoons did – rather than a westerly track.

A separate study, published in the same journal by scientists at City University in Hong Kong and Seoul National University in South Korea earlier this year, found that changes in a typhoon’s track had a direct impact on regional air quality.

Typhoons heading northwards around the vicinity of Taiwan would enhance Hong Kong’s average concentrations of hazardous ground-level ozone by 82 per cent at rural monitoring stations and 58 per cent at urban stations, the study found.

According to the latest analysis by Dr Cheng Luk-ki, head of scientific research and conservation at environmental advocacy group Green Power, most of the days when the AQHI hit 10 or the “serious” level of 10+ last year did indeed occur during tropical cyclones, which are most active from about May to October.

Affected by Typhoon Haitang and Typhoon Nesat, all 13 stations hit “serious” on July 29, 2017. The same thing happened days before Typhoon Talim whizzed by in mid-September.

But what does this mean for Hong Kong?

“Under global warming, extreme weather events will intensify but how it will lead to more air pollution needs to be further studied,” Cheng said.

But the authors of the City University study were more convinced about the impacts of climate change on regional air quality, especially if typhoon tracks continue to change.

“It can be projected that the impact of tropical cyclones will be intensified if the prevailing track change towards Taiwan persists due to global warming or climate change,” they said. “It has been suggested that this track change may continue to prevail for a few decades.”

This is the first of a three-part series on how transboundary air pollution affects Hong Kong’s air quality. Next story: The menace of ozone