Pangolin scale smugglers: a few culprits caught, but masterminds behind illegal wildlife trade evade arrest

- Despite worldwide ban, there’s big money in sending ivory, pangolin scales to China

- Hong Kong a major transit point in illegal wildlife trade, but few prosecutions so far

Sometime in the middle of 2017, Hong Kong businessman Wong Muk-nam disappeared without a trace.

The 62-year-old owned a plastic trading factory in Xingtan, a township of Foshan in Guangdong, according to a friend who lives in the mainland Chinese province but refused to reveal his name.

“We were chatting on WeChat, but suddenly he was out of reach,” he recalled. “No responses to messages, phone calls. It was really unusual because he always responded quickly.”

Then Wong’s name turned up as a key suspect in an international syndicate smuggling pangolin scales and ivory from Africa.

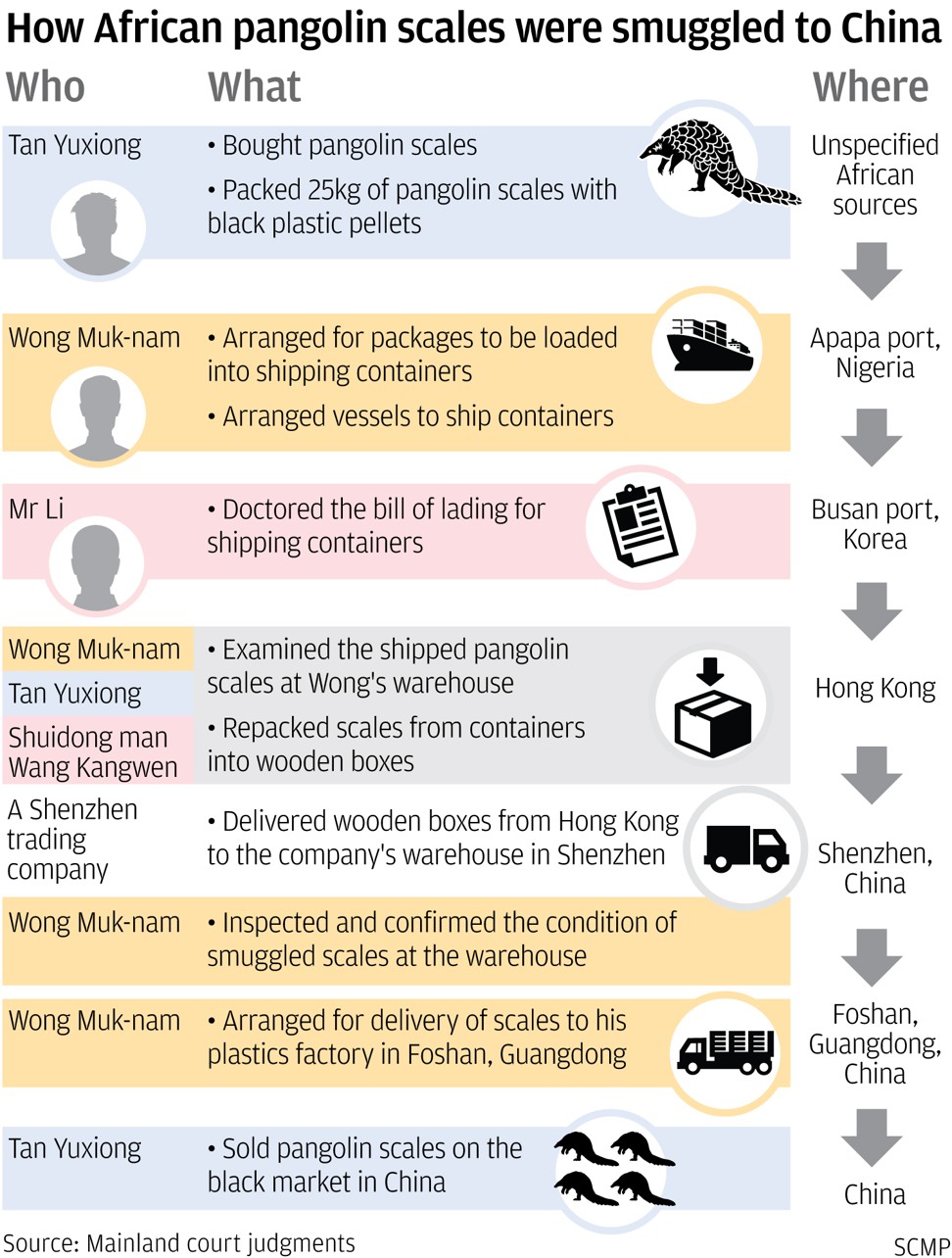

According to mainland court documents, he and his associates smuggled at least three shipments of more than four tonnes of pangolin scales worth 3.8 million yuan (US$547,500) from Nigeria to his factory between 2014 and 2016, with the cargo going through South Korea, Hong Kong and Shenzhen.

International trade in pangolin scales has been banned since 2017 because the world’s only scaled mammal is so critically endangered, mainly as a result of poaching. Even before that, special permits were needed to trade in the scales.

The illicit trade has persisted, and mainly to China, because pangolin scales are highly prized by traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) practitioners who claim they have great medicinal properties, despite the absence of scientific proof.

A kilogram of scales can sell for as much as US$760 in China, 380 times what poachers are paid in Africa, according to site visits by reporters.

Wong vanished just before Chinese authorities swooped on wildlife smugglers, following a three-year undercover investigation by an international watchdog group, the Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA).

On July 5, 2017, mainland customs officers and local police raided the premises of a suspected wildlife smuggling syndicate in the coastal town of Shuidong in Guangdong. They seized only 72.6kg of ivory, but were able to prove after investigations that the group had smuggled 8.5 tonnes of ivory and 800kg of pangolin scales.

Between 2017 and early 2019, they arrested 27 people, of whom 16 were subsequently charged and jailed for between three and 15 years. They included some of Wong’s associates.

Following international alerts by Interpol, two Chinese nationals believed to be key players in the syndicate were arrested in Nigeria and repatriated to the mainland early last year.

Two others remain on Interpol’s “red notice” wanted list, which means China hopes they will be arrested and extradited. One of them is the alleged kingpin Wong.

His friend in Guangdong claimed to know nothing about Wong’s involvement in smuggling ivory and pangolin scales.

“I only know he had a plastics plant in Xingtan,” he said.

From mainland court documents and interviews, including with some of those who were arrested and dealt with, the Post pieced together a picture of how the syndicate sourced its illicit supplies in Africa and had them shipped over by sea, or used couriers to transport pangolin scales by air.

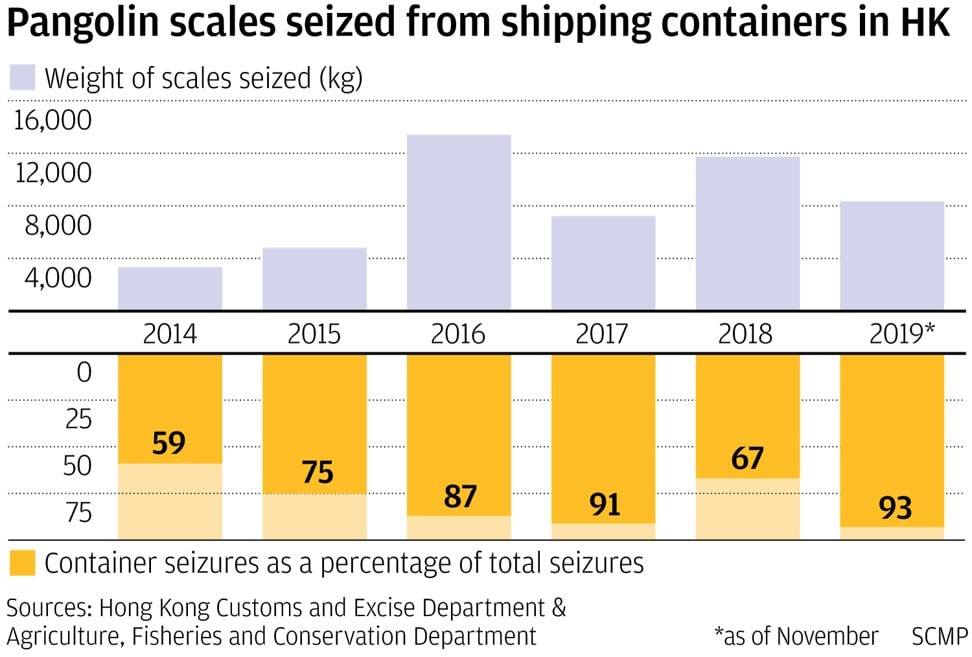

Hong Kong is known as an important transit point for moving illegal pangolin scales. Since 2014, more than 62 tonnes worth more than HK$100 million have been seized.

But Hong Kong authorities have been criticised for a disappointing record in tracking down the masterminds, and only couriers – or mules – have been jailed so far.

Wildlife conservationists have urged Hong Kong to do more to arrest kingpins like Wong, who is believed to have used his Guangdong factory as a cover while arranging the movement of illegal wildlife between Africa and China.

A winding trail from Africa to China

Shuidong man Wang Kangwen, 41, gave mainland authorities a detailed account of Wong’s role in the syndicate. Wang told police after his arrest that he met Wong in 2014 through friends.

“Some people from my hometown made a fortune by doing ivory business in Africa, so I wanted to smuggle ivory too,” he said, according to court records. “My friends said Wong had ways to smuggle ivory tusks and other goods into China through Hong Kong.”

Wang said he and Wong smuggled more than five tonnes of ivory in 2015 and 2016, with Wong arranging the routes. He began smuggling pangolin scales as well, after meeting Wong’s associate, Tan Yuxiong.

“From the end of 2014, I started smuggling pangolin scales into China with Wong and Tan,” Wang said. “Tan was responsible for getting supplies, buying and selling products. Wong dealt with customs clearance to get the goods delivered in China and I was mainly coordinating.”

According to charges drawn up by prosecutors from the People’s Procuratorate of Zhanjiang, Tan bought pangolin scales in Africa and then followed Wong’s instructions to hire people in Nigeria to pack the scales mixed with plastic pellets in 25kg packets that were put on containers.

With the cargo labelled as plastic pellets, the containers were shipped from Apapa port in Nigeria to Busan in South Korea, where another of Wong’s contacts, a Chinese surnamed Li, falsified the shipping documents to hide the Nigerian port of origin and avoid customs checks.

The contraband was then shipped to Hong Kong and delivered to Wong’s warehouse in the city. Wang said he accompanied Wong and Tan to examine the scales before they were repacked with plastic pellets into wooden boxes and taken into the mainland by a Shenzhen-based trading company.

Wong then hired a driver to pick up the goods from Shenzhen and take them to his Foshan factory.

Tan sold the scales on the black market mainly to TCM traders. Wang said the group obtained and sold pangolin scales this way three times between 2014 and 2016, making more than 3 million yuan.

Wang was sentenced to 15 years in prison. Tan was arrested early last year in Lagos, Nigeria, and repatriated to China with another person.

The sheer size of recent seizures suggests that African pangolins may be heading very quickly towards extinction

On July 10, 2017, five days after mainland customs raided the Shuidong premises, law enforcement officers searched Wong’s factory in Foshan, but found only a few kilograms of scales from local pangolins, a subspecies from Africa, as well as a bag of black plastic pellets.

Wong’s factory has since been replaced by a stainless steel factory, and the new tenants claimed to know little about his company.

Julian Newman, campaigns director of EIA, said: “On a positive note, the action by Chinese customs and other authorities has dismantled a major wildlife trafficking syndicate, even though a couple of the suspects such as Wong remain at large.”

Noting that mainland customs officials carried out thorough investigations, checking bank records and all relevant documents, he said: “They were able to build a very strong case against the suspects without actually having caught them with much in their actual hands.”

In Hong Kong, no sign of the masterminds

There are eight species of pangolin in the world, four each in Asia and Africa, and all are threatened with extinction mainly because of poaching and trafficking.

Some TCM practitioners claim pangolin scales can cure everything from inflammation and poor lactation in new mothers, to impotence and cancer. There is no scientific evidence that the scales, made of keratin just like fingernails, have such effects.

Sourcing of pangolin scales in Africa became rampant over the past five years after the Asian species – especially the Chinese and Sunda pangolins of Southeast Asia – became critically endangered.

The sale of raw scales has been banned by China’s State Forestry Administration since 2007. Processed scales with an official label may be obtained only at designated hospitals and approved pharmaceutical companies.

“The sheer size of recent seizures suggests that African pangolins may be heading very quickly towards extinction,” said Peter Knights, chief executive of the non-profit WildAid, which is devoted to ending the illegal wildlife trade.

“Chinese pangolin populations, meanwhile, have fallen by more than 94 per cent since the 1960s. At least 1.5 million pangolins have been illegally traded in the past 20 years.”

Since 2014, Hong Kong has seized pangolin scales in containers from Africa, on speedboats and fishing vessels as well as from mainland-bound trucks at checkpoints. They have also been found in the suitcases of air passengers and in express mail parcels from Southeast Asia.

Four-fifths of the 62 tonnes of pangolin scales seized in Hong Kong since 2014 came from large shipments, mostly from Nigeria.

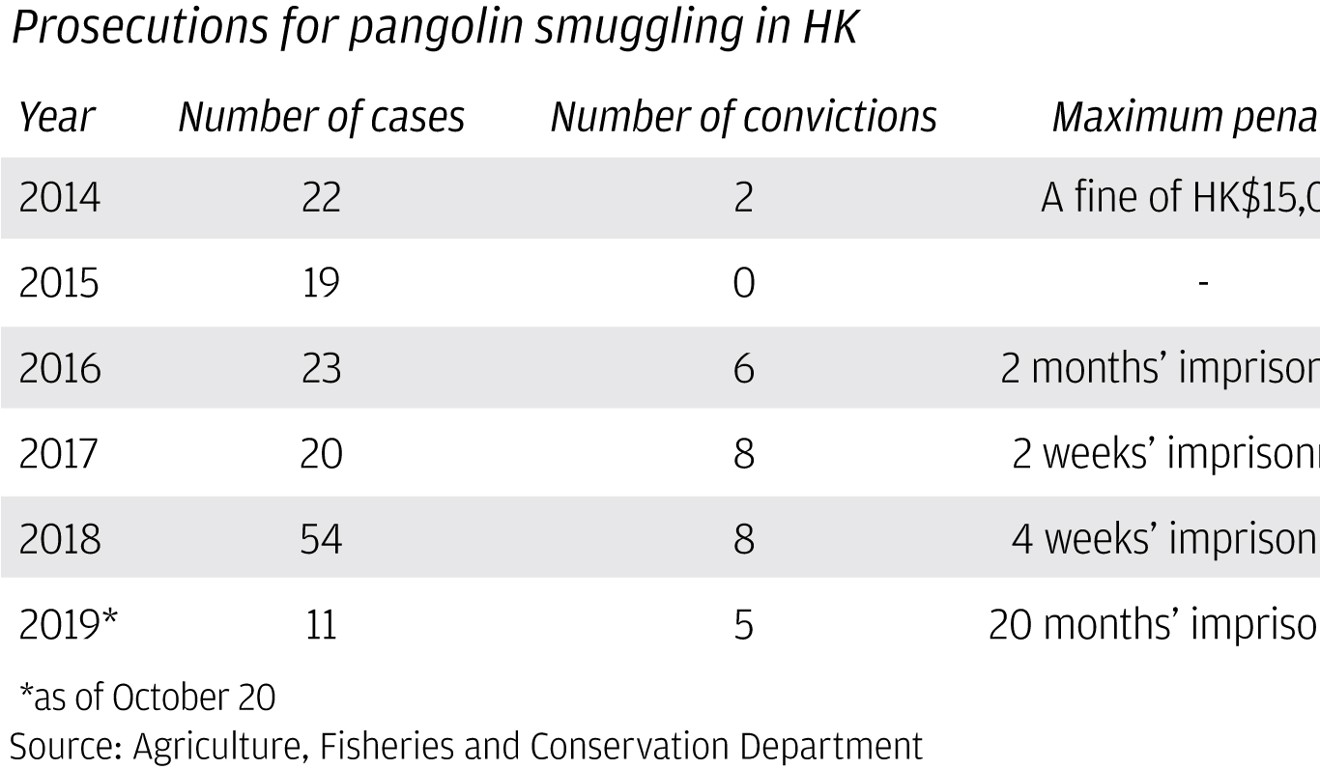

Hong Kong stepped up measures to protect pangolins through new legislation in November 2018, after the animals were placed on the highest level of international animal protection. The law imposes a fine of up to HK$10 million and up to 10 years’ jail for smuggling offences.

But out of 149 seizures from 2014 to November this year, less than 20 per cent led to convictions, according to figures from the Agriculture, Fisheries and Conservation Department, Hong Kong’s wildlife authority.

The stiffest penalty, 20 months’ jail, was imposed on Lin Jin-bao, 44, a Fujian man who was caught at Hong Kong International Airport with 48kg of pangolin scales in his luggage when he arrived from the Democratic Republic of Congo on his way to Macau.

In another case from January last year, involving 8.3 tonnes of pangolin scales and 2.1 tonnes of ivory tusks from Nigeria, Hong Kong’s customs department said its investigations were complete and it was seeking legal advice about prosecution.

As of last November, none of the shipment seizures has led to any prosecutions, according to customs.

The EIA’s Newman said: “In Hong Kong, we have the impression that they are happy to seize stuff, but they don’t really want to go far beyond that.”

He urged the Hong Kong authorities to do more, warning that smugglers could quickly regroup “unless you take stronger measures to either arrest them all or significantly disrupt their activities”.

Mules land in hot water

So far, the majority who have been dealt with have been couriers who claim they did not know what they were getting into.

The Post interviewed Xiaoxiao and Lingling (not their real names), two 41-year-olds from Guangxi who were caught in November 2018 trying to smuggle about 110kg of pangolin scales in four suitcases from the Democratic Republic of Congo to Macau via Hong Kong.

Xiaoxiao said she became a courier when she visited Congo in October 2018, after being invited there by Li Guangsheng, a man she described as a good friend originally from Guangdong. She asked Lingling, her neighbour and friend, to accompany her.

Li was already in Congo when the women arrived, and he provided them with free accommodation for a month.

Interviewed last August at the Lo Wu correctional institution in the New Territories, Xiaoxiao said Li had been in Congo for some years doing business in construction and restaurants. She was tempted when he asked her to visit the capital Kinshasa, where he was based, to look for business opportunities.

“My beauty parlour in Guangxi was not doing well,” she said. “He invited me and I was interested, because he seemed to be doing quite well there. So I took Lingling with me.”

Lingling said: “Li was nice, he treated us to food and accommodation. Before we left, he asked us to take some suitcases for him, so we agreed. He sent some local people to deliver the suitcases directly to the airport. I never opened them.”

Xiaoxiao said: “We didn’t know what was in the bags. Li told us to bring them for him, so we just did. I thought it was dry seafood.”

Last August, the pair were jailed for 11 months after they pleaded guilty. With their sentences backdated to their arrest, they were released in October.

Both were furious with Li, who remained in Africa all the time. After their conviction, unlike during the first interview, Lingling admitted the pair knew what was in their bags.

“He told us to help bring the pangolin scales. He said if we got caught, he would pay the fine and we would be all right,” she said. “We trusted him and we ended up in jail.”

After their arrest, the women tried telling the authorities that the pangolin scales were not theirs. They were allowed to call Li, but Lingling recalled angrily what he told her over the phone: “Now they are yours, even if they are not.”

Xiaoxiao said: “This has been a lesson for us.”

The whereabouts of alleged smuggling kingpin Wong Muk-nam remain unknown.

On December 15, the Post visited his wife, who lives in a public housing estate in Kwai Tsing district in the New Territories, and showed her the Interpol red notice with Wong’s photo.

“I haven’t seen him for years. I don’t know what he is doing or where he is,” she said.

She insisted she never knew he was involved in wildlife smuggling and found it all hard to believe.

As far as she knew, her husband was in the transport business in Hong Kong and spent a lot of time on the mainland.

With tears in her eyes, she said: “He is a kind person. I don’t believe he would do such things.”

Wong’s friend in Guangdong, who remains puzzled by his abrupt disappearance, hoped he would turn up because he still owed him around 200,000 yuan.

“Wong is a decent and polite person,” he said. “But he still owes me money and I don’t know what to do. I just want to know if he is still alive.”