Hong Kong’s 2050 climate goals at risk if ‘green finance’ funds don’t go to the right projects, experts say

- Green groups want money put into energy, transport sectors instead of massive incinerator project

- Projects that encourage regional collaboration on renewable energy deserve funding, experts agree

The funding, they said, should be channelled instead towards decarbonising the city’s energy and transport sectors, which are still reliant on fossil fuels and together make up more than 80 per cent of Hong Kong’s carbon emissions.

“Most of the projects currently funded or about to be funded by green bonds are old projects that have been in the government’s policy agenda for years,” said Albert Lai Kwong-tak, CEO of Carbon Care Asia, a social business in carbon strategy and sustainability innovation.

Green finance aims to move available funding towards sustainable development, and manage social and environmental risks while delivering a decent rate of return and greater accountability.

Green bonds are fixed-income financial products designed to fund environmentally friendly projects.

The global market in green bonds reached a record high of US$269.5 billion in 2020, and is projected to hit between US$400 billion and US$450 billion this year.

In Hong Kong, the number of green bonds issued in the first quarter of this year has reached US$3.1 billion, compared to US$3.3 billion in the whole of 2018, according to financial data provider Refinitiv.

Lai said proceeds from green bonds should be used to create new projects to make a real impact.

“Projects like the waste treatment plant will happen with or without the green bonds, so funding such projects does not add any environmental benefits. That’s a pity,” he said.

‘Incineration is the last resort’

In a bid to become an international green finance centre, the government announced nearly three years ago it would seek to raise HK$100 billion (US$12.9 billion) in green bonds.

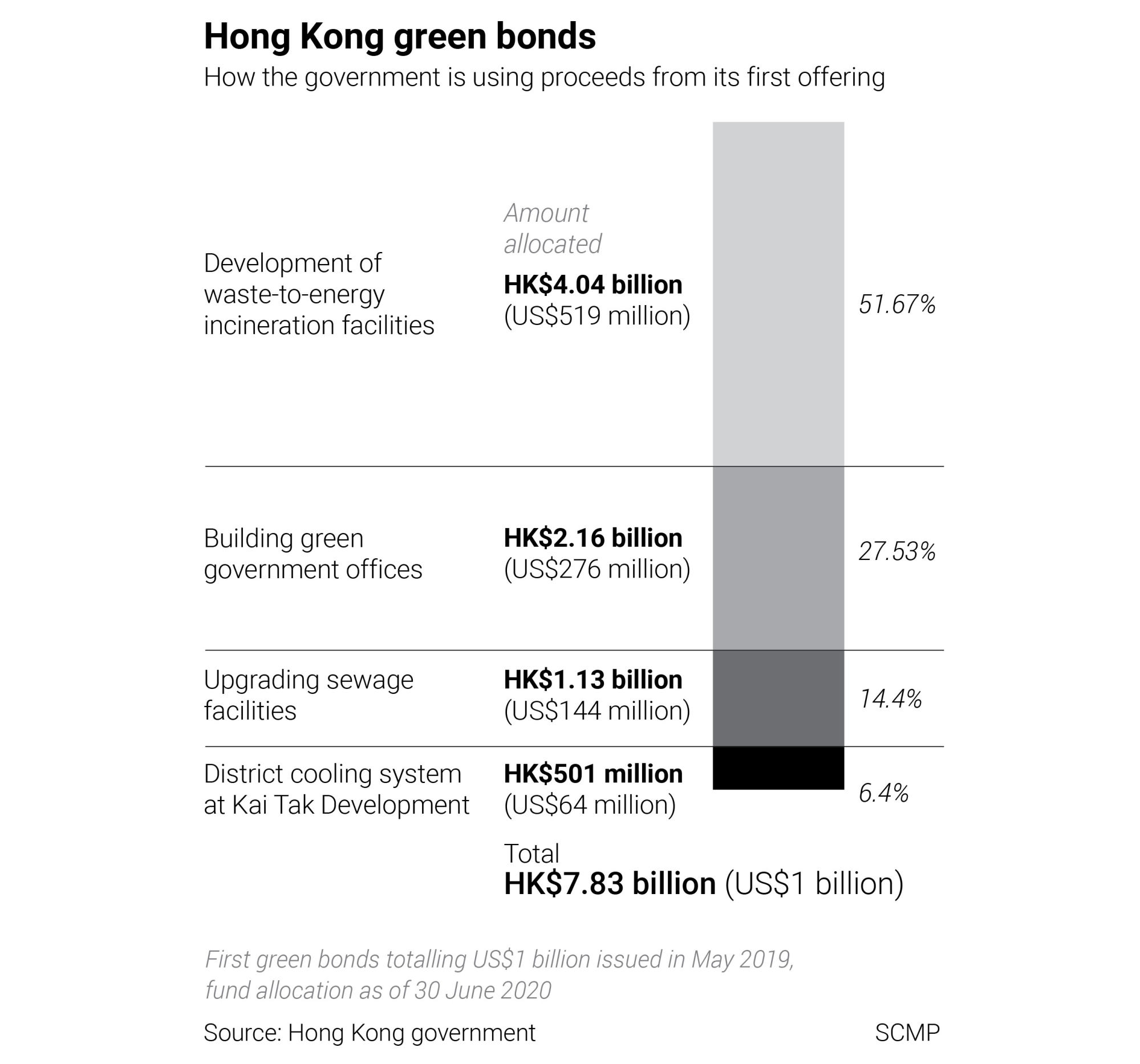

It has since issued two rounds of these bonds. The first, in 2019, raised US$1 billion while the second, in January this year, raised US$2.5 billion.

The government plan is to fund projects in eight categories: renewable energy, energy efficiency and conservation, pollution prevention and control, waste management and resource recovery, water and waste water management, nature conservation and biodiversity, clean transport, and green buildings.

According to a government report last August, half of the US$1 billion raised in 2019 went to an integrated waste management facility which incinerates trash to generate energy.

The incinerator is a key part of the city’s ambitious plan to stop sending waste to landfills by 2035, but environmentalists say it is not sustainable to rely on the incinerator to achieve waste reduction targets.

Jeffrey Hung Oi-shing, chief executive of green NGO Friends of the Earth-HK, said the city should focus on reducing, reusing and recycling waste, with incineration as a last measure for waste that cannot be recycled.

“Incineration is not a sustainable waste management solution,” he said. “For Hong Kong to decarbonise, the biggest focus should be on energy generation and transport.”

‘We need to do this at scale’

Hung said financing from green bonds should go to projects that encourage regional collaboration on renewable energy, such as with mainland China. Development of technology for electric or hydrogen-powered vehicles should also be a priority, he said.

Hong Kong bets big on electric cars, green finance, but groups say more needed

Lai agreed, urging the government to also invest in offshore wind farms and expand an existing scheme which allows people who install solar panels or wind systems on their premises to sell the energy generated to the city’s two power companies.

He said these projects could increase Hong Kong’s renewable energy production significantly. The government maintains Hong Kong will only be able to generate 3 to 4 per cent of its electricity from renewable sources by 2030.

Although the government has announced a pilot scheme for electric buses, Lai said such small scale projects were moving too slowly.

“We need to do this at scale. The government will say it is running pilot schemes but this is of no use,” he said.

The Financial Services and Treasury Bureau said proceeds from the government green bonds were currently being used to finance or refinance major public green projects already approved by the Legislative Council’s Finance Committee, but added it had plans to expand the scope of the programme.

It said it was currently considering potential projects submitted by various government departments for funding under the second issuance of green bonds.

John Yeap, a climate change and sustainability consultant at law firm Pinsent Masons, said green finance still faced challenges as there was still no clear, globally accepted definition of “green”.

That was needed so green fund providers could put their money into projects and investments that were acknowledged to indeed be environmentally friendly and could be verified, he said.

Hong Kong’s climate action to focus on energy, electric vehicles, cutting waste

Agreeing, Lai said Hong Kong should take the lead and develop its own definition.

The Green and Sustainable Finance Cross-Agency Steering Group, co-chaired by the Securities and Futures Commission and the Hong Kong Monetary Authority, has said it hopes to adopt a standardised definition being developed by a working group led by China and the European Union, which could happen by midyear.

But Lai said: “I don’t think Hong Kong should wait, because they have been discussing it for a long time.”