Advertisement

Coronavirus: refugees welcome Hong Kong’s vaccination offer but decry government handling of the crisis

- Better late than never, says woman who fled sexual violence, after government opens up vaccinations to 13,000 torture claimants, refugees

- Refugees recount ‘stressful, lonely’ Covid-19 ordeal, say government did not do enough to support them at start of the crisis

Reading Time:3 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

5

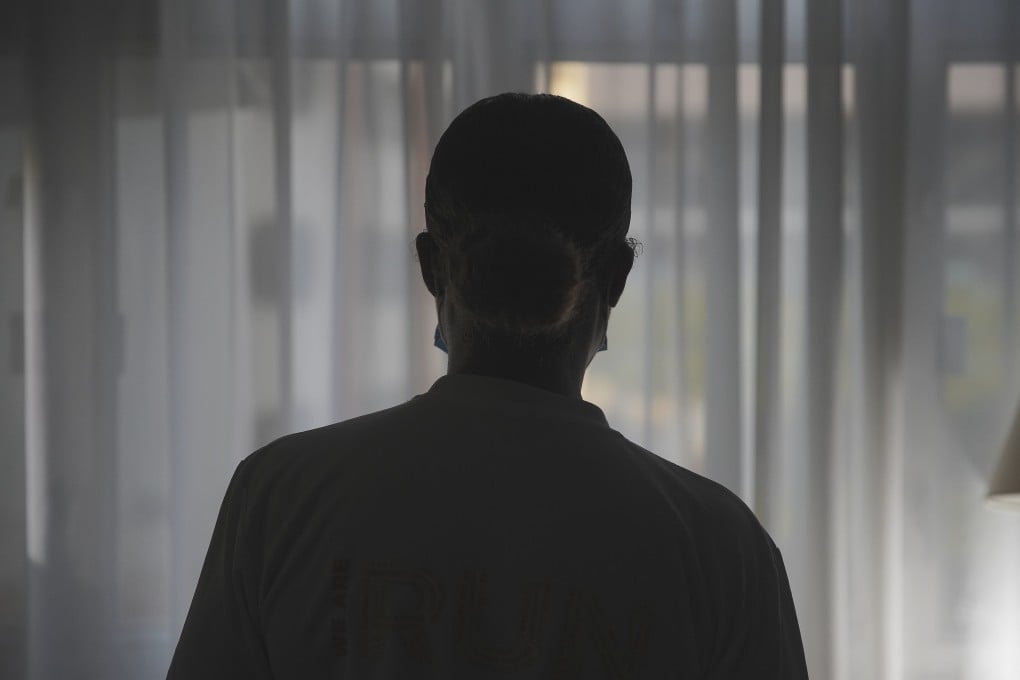

Sara* was exhilarated to learn the Hong Kong government was expanding its Covid-19 vaccination programme to her and fellow torture claimants, the city’s version of asylum seeker status.

For the first time since the start of Hong Kong’s pandemic battle, the UN-recognised refugee said she felt a sense of belonging in the city.

“Even though it’s a little late, we are included,” said the mother in her late 20s, who fled sexual violence in East Africa and is in Hong Kong awaiting relocation to a third country.

Advertisement

“It’s a really good thing to be vaccinated for society and our family. We can protect ourselves and we can protect others.”

But the time it took for the government to offer them jabs also served as a vivid reminder of how one of society’s most vulnerable groups had been treated differently over the past year or so, she said.

Advertisement

Sara recalled how she scurried from one supermarket to another looking for food and sanitiser for her young children amid bouts of panic buying when the coronavirus crisis struck last year.

Advertisement

Select Voice

Select Speed

1.00x