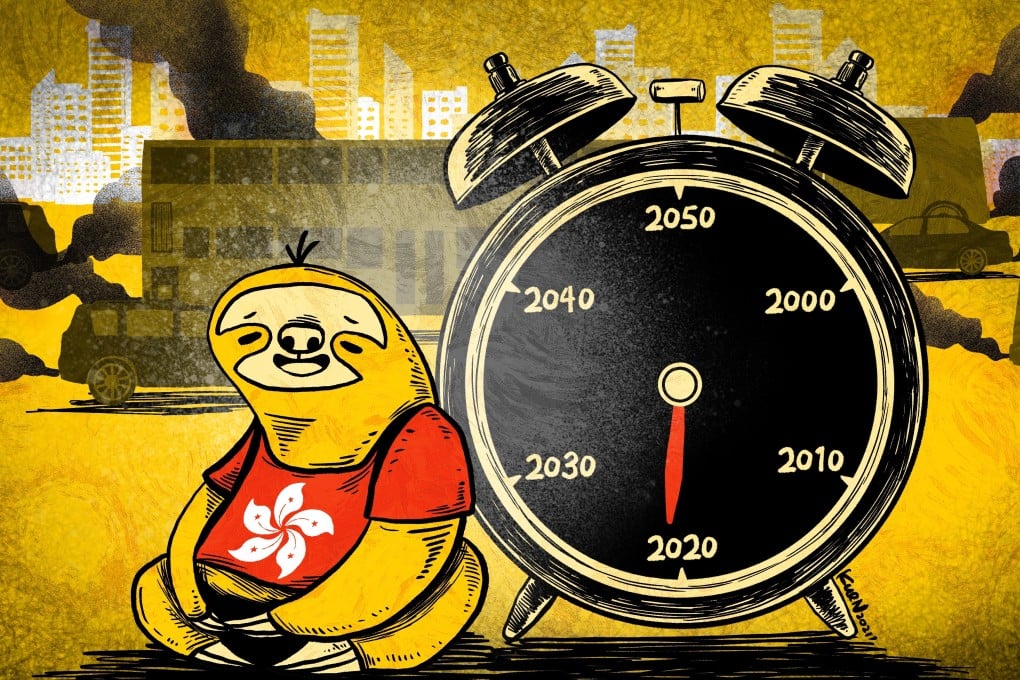

Climate change: Hong Kong must set clear targets, timelines before it becomes too late to avoid weather disaster, experts warn

- City doing ‘too little, too slowly’ despite having talent and technology to lead climate action

- Slow progress with promoting electric vehicles just one example of city trailing mainland, others

Humanity’s need to tackle climate change is more pressing than ever, with the United Nations warning last week global warming would accelerate at a faster-than-expected pace over the next 20 years. In this four-part series, the Post examines its impact on the city, how the Hong Kong government can best play catch-up, and who is walking the talk in the private sector. Part three looks at what Hong Kong needs to do to avoid the threat of disaster brought on by extreme weather patterns. Read part one here and part two here.

Hong Kong is also aiming to reach carbon neutrality by that year, which means it must take drastic action to reduce the amount of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases it produces by cutting the use of fossil fuels.

Observers note a lack of concrete plans to cut emissions in the city’s most carbon-intensive sectors such as energy and transport. In this, Hong Kong trails mainland China, which has pledged to increase the use of renewable energy and expand its forests.