Old and new worlds collide as Hong Kong’s farmers find themselves overrun by rampant development in the New Territories

- In the last of a three-part series on the impact of a government plan to develop new towns, the Post explored how life has changed for those affected

- Building projects in Hong Kong’s north hastening the end of a traditional way of life

Twenty years ago Chan Ki-kau thought his life could not have been better. Tending to 4,000 sq ft of banana groves, vegetable patches and fruit trees, he was a happy and self-sufficient farmer.

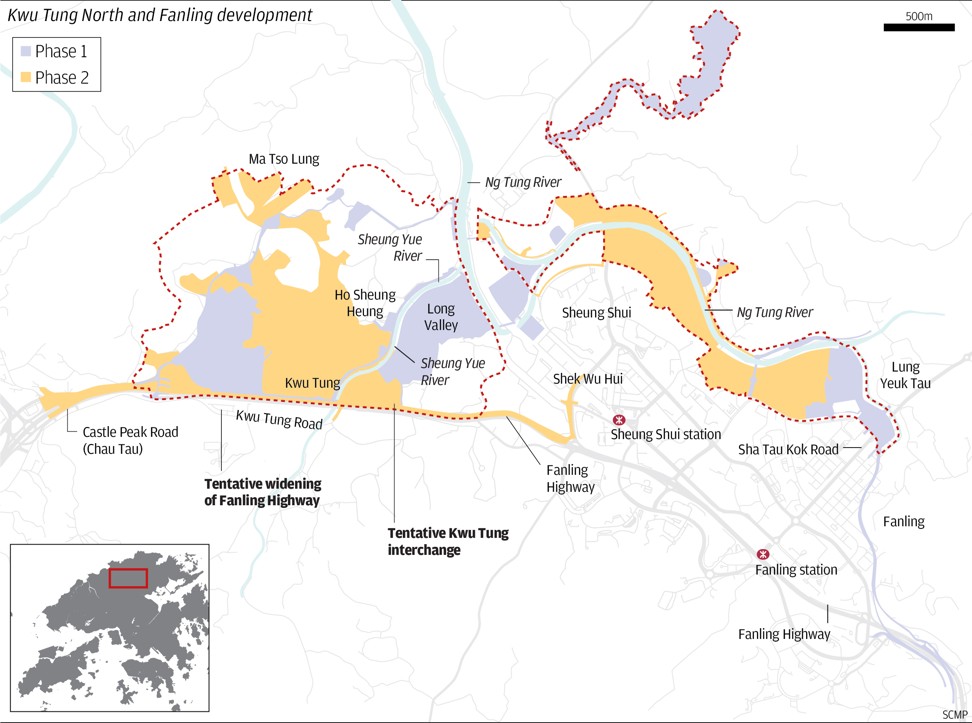

But in 1998 the government’s announcement that it was planning to build new towns in Hong Kong’s rural north, including near Chan’s little village in Fanling, turned his idyllic country life upside down.

Sensing an opportunity to make a profit, Chan’s landlord tried to have him evicted. When the farmer refused to leave, the landlord took him to court in 2000.

That was the beginning of a 10-year fight against three consecutive owners of his farm.

“I cannot even describe the hardship I went through,” the 72-year-old said. “No one can understand the amount of pressure I faced every day in those 10 years.”

Chan secured his right to continue to rent the farm in 2010, when the site’s present owner, a subsidiary of Henderson Land Development, withdrew its lawsuit. By then his farm had become largely overgrown.

During its heyday, Ma Shi Po was home to 700 families, many of them farmers. They grew seasonal vegetables to sell on the farms or in nearby markets.

Chan is now just one of only 100 remaining families – most of whom fought against landlords to keep their homes – to be affected by the decade-old Fanling North and Kwu Tung North new town projects, which the government is pushing ahead to increase housing supply to address the city’s unaffordable property prices and overcrowding.

In the project’s first phase, some 450 households will need to relocate starting from the second half of the year, while the whole project will see up to 1,500 households make way for 71,800 flats by 2031.

Hong Kong to push ahead with controversial plan to build new towns

Development officials, claiming a people-oriented approach, last year rolled out an enhanced compensation package to ease opposition, giving those affected priority in relocation, waiving a means test, and raising the cap of a cash allowance.

Under the package, those who have lived in a licensed squatter home for at least seven years and have not owned another property can choose to move into a relocation housing estate planned nearby, without the need for a means test.

The estate is expected to be completed by 2023 at the earliest. Before its completion, the government will provide transitional flats for those eligible families.

For those who can prove they have lived in their licensed squatter homes for two years continuously and have not owned any other property, they are also eligible for a cash allowance of between HK$60,000 (US$7,644) and HK$1.2 million, based on the sizes of their homes and how long they have lived there.

But Chan, among many others in the village, remains a diehard opponent to development. He said the package did not look as generous as it seemed, as only homes of more than 1,000 sq ft could get HK$1.2 million, while most squatter homes in the village were only 400 sq ft.

Other villagers also dislike the idea of moving into a condominium from their quaint farm houses.

“If I had wanted to move into a high-rise, I would have applied for public housing long ago,” said Liu Siu, 87, who settled in the village when she was 18. Her two sons were born in their house.

She has been growing lychee and longan trees, and vegetables on her patch of farmland, which she also rents from Henderson Land.

“Living here, you can chat with everybody as soon as you go out. Life is quiet. You feel healthy,” Liu said. “Living in a building you won’t get to know anybody.”

Evicted farmers can continue livelihood on public land, but can’t build homes

The government said the improved compensation package had yielded positive results. By January, land officials had contacted 80 per cent of the villagers affected by the first phase of the projects, among whom more than 60 per cent submitted documents to prove their eligibility.

But for some 30 farming families in Ma Shi Po, the government has failed to offer them a way to continue living off the land.

Becky Au Hei-man, daughter of a farmer in Ma Shi Po who set up a community farm with activists to save the village, criticised officials for providing no suitable farmland for relocation. Even if farmers did manage to move, they would not be allowed to build houses on their farms.

“Farmers harvest very early in the morning, and they need to tend to their crops all day long,” she said. “They will not survive if there is no integration of living and farming.”

For the remaining villagers in Ma Shi Po, any hope they might have had of passing their remaining days in peace and quiet have been dashed by the construction of a private housing estate by Henderson Land on what used to be part of the village.

“The government is helping developers evict villagers by introducing such an arrangement,” Au said, referring to a process where a developer owning 40,000 sq ft of farm or more in the new town areas can develop first without waiting for the whole project to begin.

On the day the Post visited, conversations with villagers were drowned out by loud banging or drilling, while residents complained about the construction leaving cracks in their walls.

“We used to wake up every morning hearing birds chirping and frogs croaking,” villager Lo Wing-sun said. “Now we are waken up every day by jackhammering and pile driving.”