Without jobs, some in Hong Kong tighten belts and deplete savings as they face an uncertain future

- Pandemic robs families of livelihoods, leaving many anxious, desperate for better times

- Some forced to put shame aside and apply for social welfare

This is the first instalment of a five-part series in which the Post takes a look at unemployment in Hong Kong. You can read part two here, part three here and part four here.

Some have lost their jobs. Others have been told to go on unpaid leave, or take sharp pay cuts while waiting to find out if they will ever return to the jobs they once had.

04:33

Double punch for Hong Kong’s economy from coronavirus following months of civil unrest

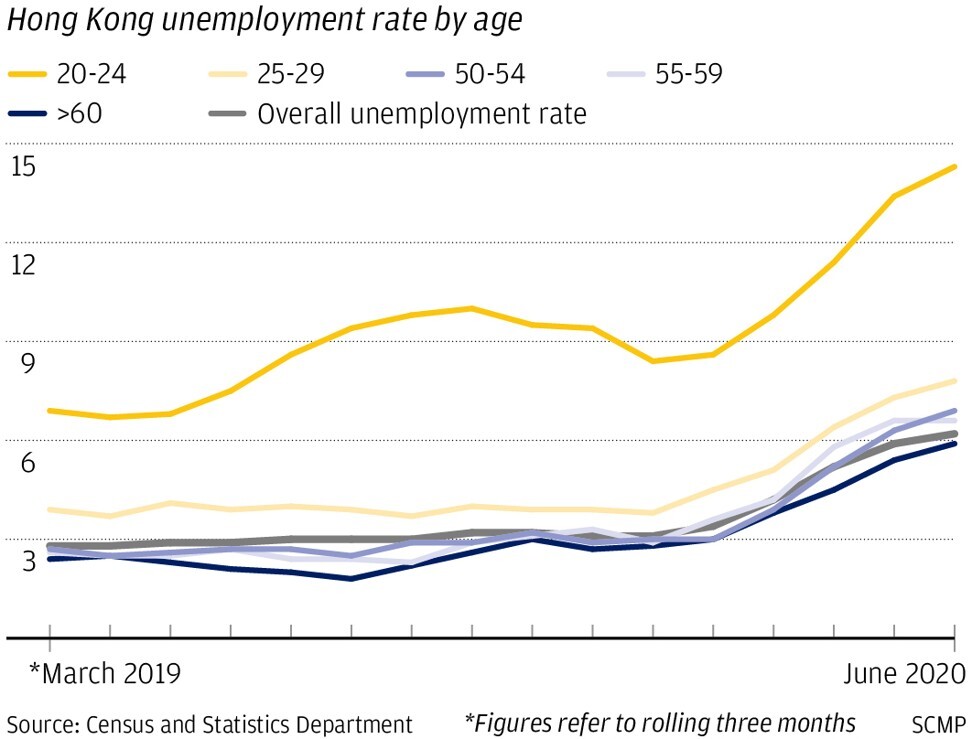

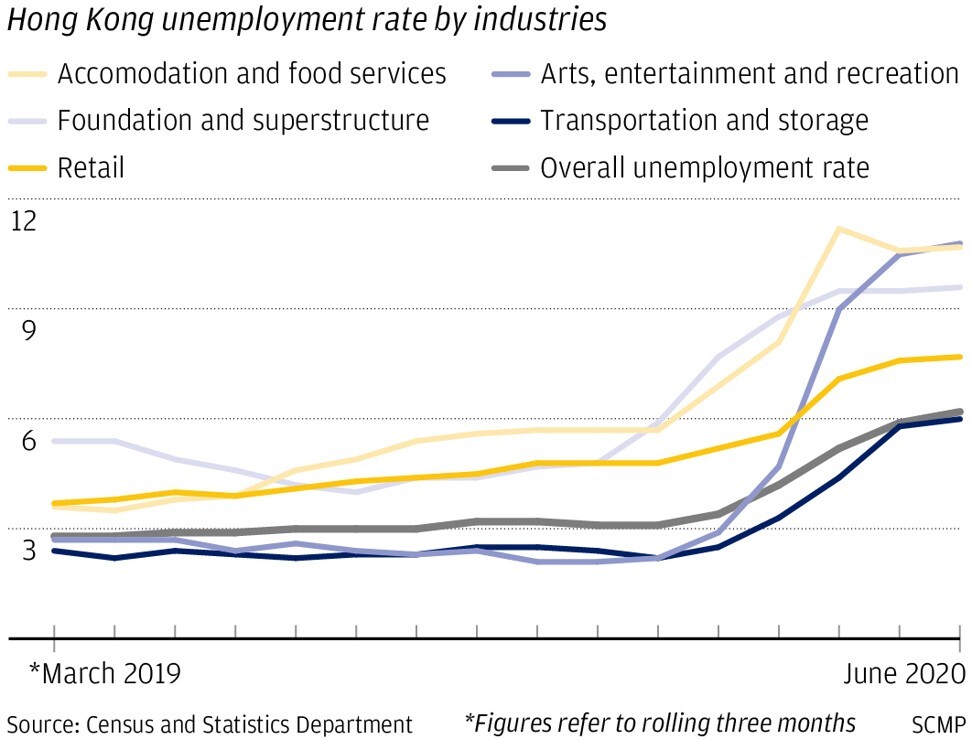

The ranks of the unemployed swelled to 240,700 for this three-month period while the number of underemployed rose 5.77 per cent to 142,000.

Hong Kong’s jobless rate rose across all major economic sectors, with the food and beverage sector hardest hit at 14.7 per cent, followed by the construction sector at 11.2 per cent and arts, entertainment and recreation at 10.8 per cent, the hotel sector at 9.5 per cent and retail at 7.7 per cent.

The jobs crisis promises to remain a thorny problem. In this first instalment of a five-part series, the Post speaks to workers struggling to cope, fearing the worst and looking for hope.

‘I only work five or six days a month’

Xu Guiquan, 62, is despondent as he ponders what lies ahead.

A mainland migrant who does painting, repair and renovation jobs, he has been mostly out of work since the pandemic arrived.

“I go out every day asking around for work, but mostly to no avail,” said Xu, who lives with his wife, a Hongkonger also 62 and jobless, in their tiny 70 sq ft cubicle in Cheung Sha Wan.

Hong Kong retail shrinks by a third for first half of 2020 amid pandemic

The unrest affected his livelihood when he could not get to work sites, as many roads were blocked by protesters, and his income fell to about HK$8,000 per month.

The pandemic brought even more misery. Since February, his income has shrunk to under HK$6,000 a month, of which HK$4,000 goes to rent.

03:20

Hong Kong’s class of 2020 fears becoming ‘lost’ generation as Covid-19 shakes the global economy

“Many customers have put their decorating or repair plans on hold, and many businesses have shut down,” he said. “For the past few months, I’ve only been working five or six days each month.”

Without savings, the couple have tightened their belts, buying only the cheapest frozen meat and canned food.

“Fortunately we received the one-off HK$7,500 government relief for those in the construction sector, or we wouldn’t even be able to pay for our meals,” he said.

The couple have not asked their children for help, not wanting to trouble them as neither earned much on the mainland.

If the situation does not improve, Xu and his wife might have to apply for social welfare, or even return to the mainland.

Still, he said, there were others worse off. “I know workers who are in a much more wretched state. Single, penniless and without work, they only have a 3 sq ft bunk bed” he said.

Hong Kong’s coronavirus-ravaged economy shrinks 9 per cent in second quarter

‘I don’t want to rely on social welfare forever’

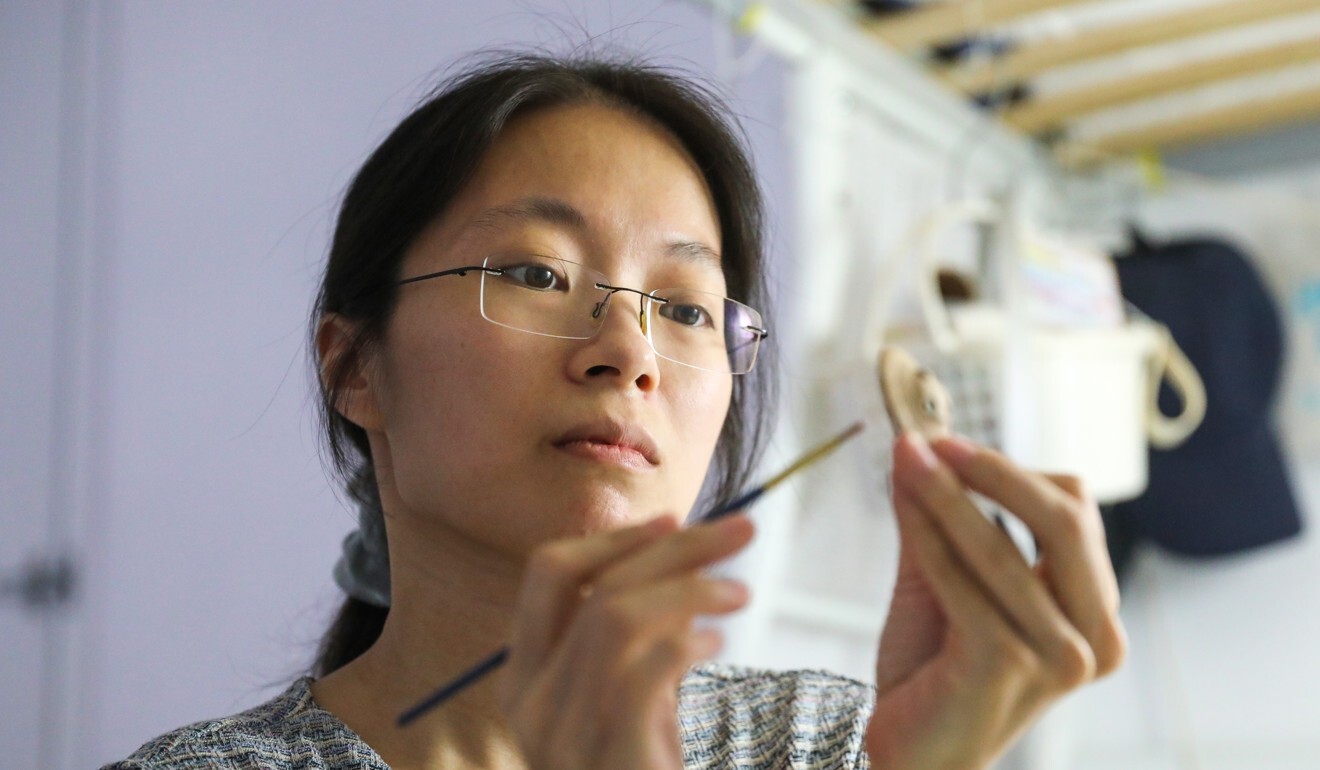

Single mother Diane Lau, 34, felt desperate in February when she lost her job as a ceramics instructor because there were too few students.

The boss of the studio where she taught gave her no notice and paid no compensation. He just told her to stop coming to work.

“I was in agony,” she recalled. “I had to pay a monthly rent of HK$2,000 for my public housing flat and I didn’t have savings.”

Divorced with a 12-year-old son, she used to earn HK$7,000 a month. Her ex-husband did not contribute anything, she said.

I really feel ashamed asking my mum to help

To get by, she and her son only wore second-hand clothes and avoided eating out or even using public transport unnecessarily.

She went to the Labour Department for help with the abrupt termination of her services. Then she went to the Social Welfare Department, something she always considered a last resort.

“I’ve been reluctant to apply for social welfare assistance as I always want to be self-reliant,” she said. “But I have no other way, as I don’t think I’ll be able to get a job in the next one or two years.”

It took three months before the first dole payment of about HK$5,000 arrived and while waiting, she borrowed HK$10,000 from her mother, a school cleaner.

“I really feel ashamed asking my mum to help,” she said.

A graduate in philosophy, she derives satisfaction making ceramic earrings, pendants, bracelets and pots, occasionally selling her creations at flea markets.

Despite the low income, being an instructor gave her time to care for her son, who starts secondary school after the summer holidays.

The uncertainty brought by the pandemic has made Lau ponder the future, and she has been thinking of starting an online business selling her ceramic items.

“I don’t want to rely on social welfare forever,” she said.

‘Sometimes, I can’t help weeping’

Senior waitress Apple Lam*, 44, made about HK$15,000 a month after working more than eight years at a Chinese restaurant. Then, in March, she was told to go on unpaid leave.

“Since that day, I’ve felt so anxious and troubled, and I suffer insomnia every day,” said the mother of two girls, aged nine and 18.

Her husband, a construction sector worker, was jobless between January and May. He used to earn up to HK$20,000 a month, but has been bringing home only about half that amount in recent months.

Their expenses exceed HK$10,000 a month, including support for his parents.

“Sometimes when I tell others about my situation, I can’t help weeping,” said Lam.

She became more upset recently when she learned that her employer asked some temporary staff to start working full-time, without first recalling long-serving employees like her.

“They didn’t dismiss us, but didn’t ask us to go back to work,” she said. “What does it mean? We also have to eat. We have received zero income for several months.”

Her guess is that the restaurant preferred to hire cheaper new staff and hoped senior employees would resign on their own.

Hong Kong’s oldest bookshop Swindon to close after decades

“Of course it’s unfair. We worked so hard when business was good,” she said.

Her husband qualified for the one-off HK$7,500 pandemic relief payment for those in the construction sector, but Lam worries when she thinks about the future.

“Our savings are nearly used up,” she said.

‘Being a salesman is all I know’

Billy Chan Chun-wai, 30, became a salesman after high school and was earning HK$15,000 a month plus commissions and bonuses before Hong Kong’s anti-government protests broke out last year.

Then the fashion retailer he worked for went bust. Now the pandemic has worsened his prospects of finding full-time work.

He applied for nearly 20 full-time retail jobs in the past five months, but did not receive a single response.

“This is the longest rest I’ve had since I left school,” Chan quipped. “It is very difficult to find a full-time job, and I don’t think I’ll be able to land one in the coming months.”

He spent most of June as a temporary salesman with the Sogo department store in Causeway Bay, earning $10,000 a month.

Without strong academic qualifications, he cannot see himself working in anything other than sales.

Single and living with his parents, he has cut back on spending and going out with friends.

“I still contribute HK$3,000 a month for my living expenses to my parents and have been drawing on my savings,” he said. “I will just have to tighten my belt until I find a full-time job.”

Budding filmmaker makes masks for now

Before the projects dried up in January, Bill To, 26, was a freelance production assistant earning HK$6,000 to HK$7,000 a month working on short films, videos and stage shows.

The cinematography graduate of Open University had to put aside her dreams of working on hit movies some day, and focus on making ends meet.

To now spends her days as a factory worker in Lai Chi Kok, hunched over machines turning out masks, the most sought-after product in the pandemic.

She got the job in mid-May and it pays HK$15,000 per month, more than she earned before.

“I couldn’t get any jobs since January as investors halted their production projects due to the border closures, quarantine and social-distancing rules, as well as the closure of many venues. My income went down to zero,” she said

To, who is single, lives with her parents. Her mother is a security officer and her father, a taxi driver. She has an elder brother.

She said she began to panic in March, when she could not tell how long she would remain jobless. “I didn’t feel good, depending on my parents for money,” she said.

Covid-19 measures are ‘final straw’ for struggling Hong Kong restaurants

A friend helped her land the job at the factory, where her colleagues include former clerks, hotel staff and tour agents, who all lost their jobs. There were family breadwinners with children, and everyone was desperate for work.

“My current job is a temporary shelter, and at least I can earn a living,” she said. “I’ll continue to look for jobs in filmmaking, where my true passion lies. I’m sure there will be a way out.”

‘I worry,’ says artist deep in debt

Freelance artist Jaffe Tse, 37, used to earn nearly HK$20,000 a month producing advertisements and teaching art classes. He never imagined he would land in debt.

Jobless since February, the single man had to rely on his savings to get by, including paying rent of more than HK$7,000 a month for his studio at an industrial building and for his flat.

Although he found jobs that paid a few thousand dollars, he could not make ends meet and borrowed from a bank, only to find repaying the loan a huge burden.

“It’s so big, I can’t handle it,” he said. “I feel anxious and I worry.”

Tse said he knew of many workers in the arts who had switched jobs because of the downturn, including a photographer who started working at a petrol station.

“I will probably seek a full-time job in a company,” he said, aware his freelancing days might be over.

‘I’m afraid of losing my job’

Before the pandemic, Anna Chan*, 25, earned more than HK$25,000 a month as an airline marketing manager.

Then international travel ground to a halt in late March, and she was told to take leave from April, with her pay slashed to HK$9,000 per month.

By the end of June, her company announced that it was expecting massive losses and would have to scale back the workforce by 20 per cent.

Chan, who lives with her parents in Tsing Yi, is now waiting to learn if her position will be axed. She was with the airline for two years.

In the meantime, she has started working with her family’s e-commerce business selling women’s health products, but is focused on saving money.

“I am afraid of losing my job, but I guess my situation is not as bad as my colleagues who have to support their kids or parents,” she said.

‘Money is going to be very tight’

Kay Wong started working in the hotel industry right after Hong Kong’s economy was hit hard by the global financial crisis and swine flu epidemic between 2007 and 2009.

With her degree in hospitality, she stayed for nearly a decade, and was earning about HK$20,000 a month working at the front office when the pandemic struck.

In March, the four-star hotel halved her salary to HK$10,000 and told all staff to take nine days of unpaid leave each month.

“The situation now is much worse than when I first joined the industry,” said Wong, who is in her 30s.

Her monthly rent of HK$9,000 leaves her with very little, and she has had to start using her savings.

“Money will be extremely tight in the coming months,” she said. “It’s going to be difficult.”

“My biggest worry is that the hotel might start firing staff if the business situation does not improve,” she said, adding: “I don’t want to burden my elderly parents and make them worry.”

* Names of interviewees changed at their request