Explainer | Is Hong Kong a great place to live? How quality of life changed post-handover

- Crime has come down, city’s transport networks have grown, people have more leisure choices now

- A big downside for residents is how homes have shrunk, cost much more and the queue is longer

With more than 7 million people, Hong Kong is both a bustling high-rise metropolis and a city with wide open spaces. It is a global financial centre and a place where conservation, heritage and the arts have come to matter more.

Since its return to Chinese sovereignty in 1997, the city had more than two decades of boisterous civil society activism, street processions and demonstrations. All that changed in the wake of 2019’s social unrest as Beijing introduced a national security law and sweeping electoral reforms.

But has Hong Kong become more liveable for residents who call the city home? The Post examines some indicators of whether life has changed for the better over the past 25 years.

1. Has the housing situation improved?

No. Just ask poor Hongkongers languishing in the queue for public rental housing and middle-class homebuyers who cannot afford the exorbitant prices of private flats.

The wait for a public rental flat is almost as long today as in 1997. The average waiting time was 6.6 years in 1997, dropped to 1.8 years in 2007, but by March this year, stood at 6.1 years, the longest in more than two decades. While waiting, many of the city’s poorest live in tiny, subdivided spaces, the worst housing option.

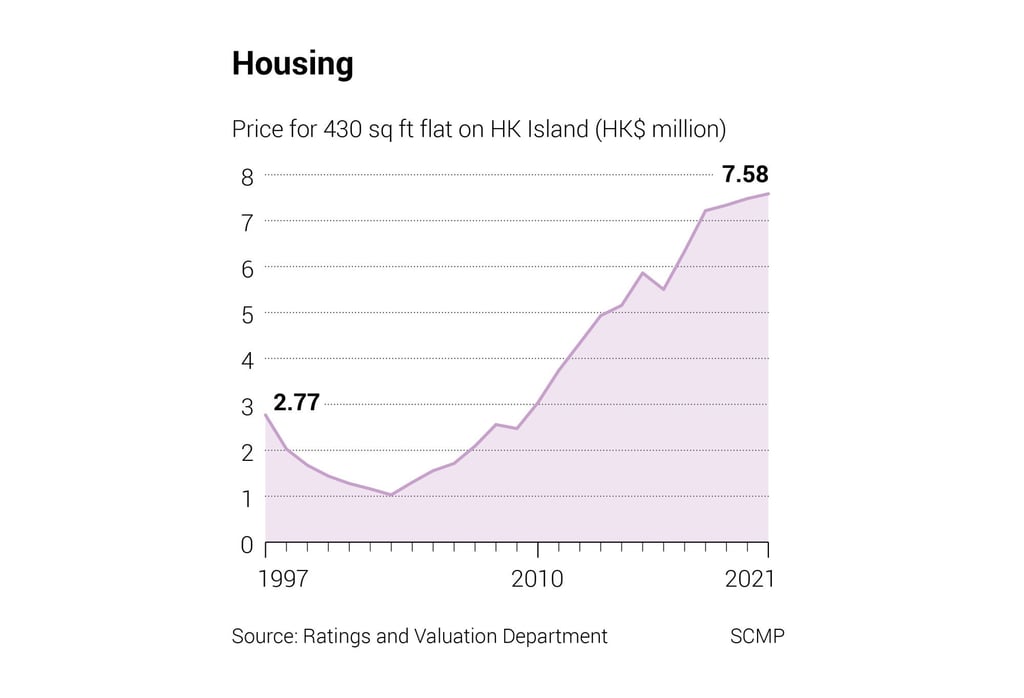

Meanwhile, private home prices soared by 136 per cent between 1997 and the first quarter of 2021. In 1997, a 430 sq ft flat on Hong Kong Island would have cost HK$2.77 million (US$353,000. Early last year, it was HK$7.6 million. The price of a flat of the same size in the New Territories would have gone up from HK$2.4 million to HK$6.1 million over the same period.

As private homes have become pricier, living space has shrunk with the trend of nano flats. These tiny housing units, as small as 200 sq ft, rose from 0.2 per cent of total new units offered in 2010 to 10.3 per cent in 2020, according to think tank Liber Research Community. The entry price of Soyo, a new nano flat project in Mong Kok, started at HK$3.38 million for flats of 152 to 228 sq ft.

“Hong Kong’s housing woes are created by many layers of problems, but all can be traced back to the government’s land administration, housing and taxation policy,” said Brian Wong, a Liber member.