Explainer | Is Hong Kong a great place to live? How quality of life changed post-handover

- Crime has come down, city’s transport networks have grown, people have more leisure choices now

- A big downside for residents is how homes have shrunk, cost much more and the queue is longer

With more than 7 million people, Hong Kong is both a bustling high-rise metropolis and a city with wide open spaces. It is a global financial centre and a place where conservation, heritage and the arts have come to matter more.

Since its return to Chinese sovereignty in 1997, the city had more than two decades of boisterous civil society activism, street processions and demonstrations. All that changed in the wake of 2019’s social unrest as Beijing introduced a national security law and sweeping electoral reforms.

But has Hong Kong become more liveable for residents who call the city home? The Post examines some indicators of whether life has changed for the better over the past 25 years.

1. Has the housing situation improved?

No. Just ask poor Hongkongers languishing in the queue for public rental housing and middle-class homebuyers who cannot afford the exorbitant prices of private flats.

The wait for a public rental flat is almost as long today as in 1997. The average waiting time was 6.6 years in 1997, dropped to 1.8 years in 2007, but by March this year, stood at 6.1 years, the longest in more than two decades. While waiting, many of the city’s poorest live in tiny, subdivided spaces, the worst housing option.

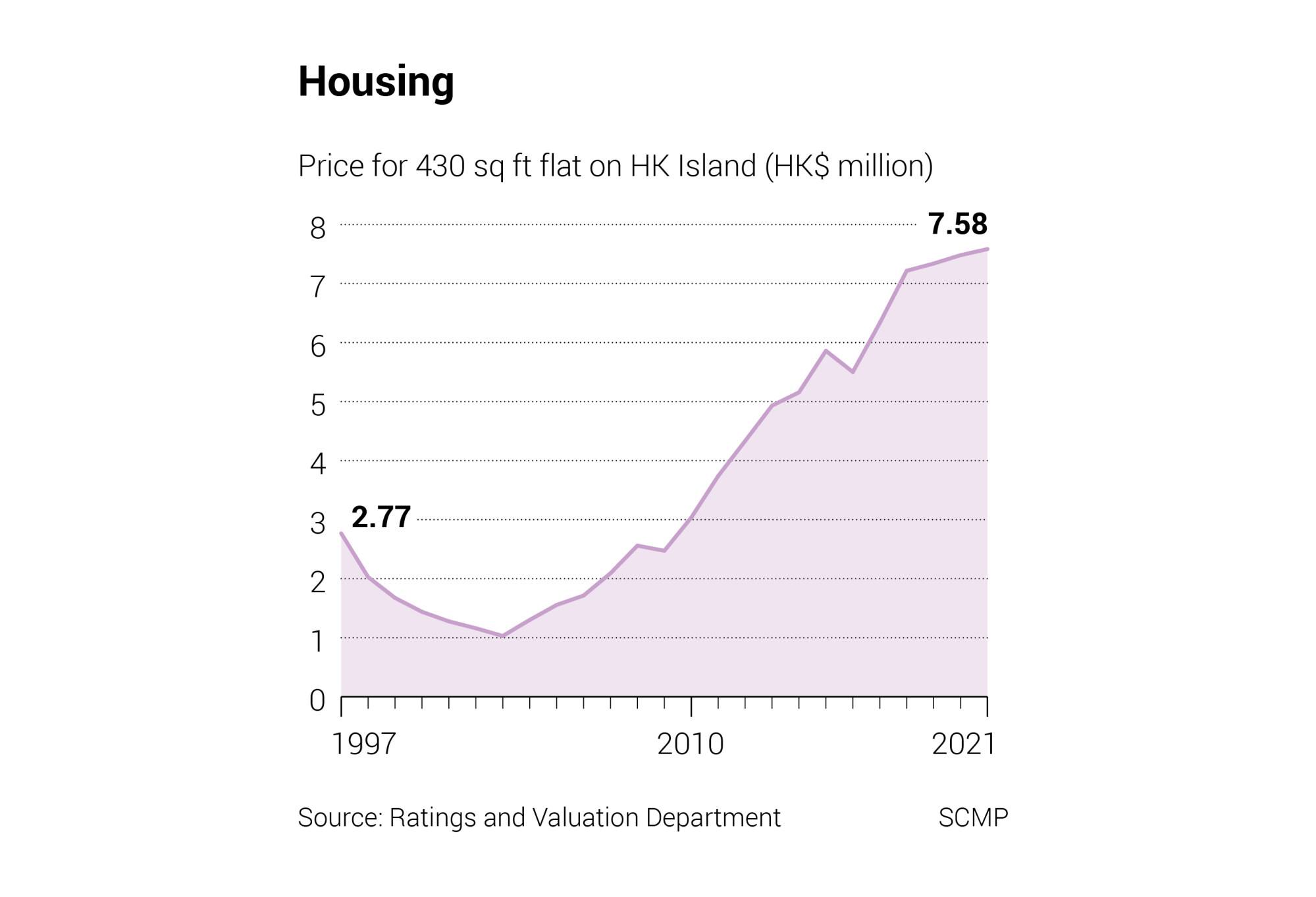

Meanwhile, private home prices soared by 136 per cent between 1997 and the first quarter of 2021. In 1997, a 430 sq ft flat on Hong Kong Island would have cost HK$2.77 million (US$353,000. Early last year, it was HK$7.6 million. The price of a flat of the same size in the New Territories would have gone up from HK$2.4 million to HK$6.1 million over the same period.

As private homes have become pricier, living space has shrunk with the trend of nano flats. These tiny housing units, as small as 200 sq ft, rose from 0.2 per cent of total new units offered in 2010 to 10.3 per cent in 2020, according to think tank Liber Research Community. The entry price of Soyo, a new nano flat project in Mong Kok, started at HK$3.38 million for flats of 152 to 228 sq ft.

“Hong Kong’s housing woes are created by many layers of problems, but all can be traced back to the government’s land administration, housing and taxation policy,” said Brian Wong, a Liber member.

“The government has conceded too much to developers in the past 25 years, and the general public as a whole has paid a heavy price by being forced to live in cramped, unaffordable space.”

2. Does it cost more to live in Hong Kong now?

Yes. Although incomes have gone up, that has been outpaced by the rising cost of housing, food and transport.

The median monthly wage for Hongkongers for the period May to June last year was HK$18,700 (US$2,400), up about 68 per cent from HK$11,113 in April to September 1997.

The price of a Big Mac hamburger from fast food chain McDonald’s, which has more than 200 outlets across the city, more than doubled from HK$10.20 (US$1.30) in 2000 to HK$22 this year. A can of fried dace with salted black beans, a staple in the pantries of grass root homes, costs nearly five times more, rising from HK$5.60 in 1997 to HK$32.90 this year.

Hong Kong has a long way to go to fix its widening wealth gap. The city’s poorest residents received some relief when the government introduced a minimum wage in 2011. Starting at HK$28 an hour, it is now HK$37.50, with calls to raise it further.

Around 1.65 million people, almost one in four in the city, were considered to be living in poverty last year, earning only half the median household income. That was the highest rate of poverty since records began in 2009.

3. Is it easier to get around the city?

Hong Kong has invested heavily in improving transport networks and connectivity, especially by train, slashing travel times within the city and with mainland China since the handover.

Major rail projects include the Guangzhou-Shenzhen-Hong Kong Express Rail Link, the South Island line reaching Aberdeen, and the Sha Tin-Central line with the East Rail line extension, connecting Tuen Mun with Kowloon and New Territories East, as well as Admiralty with the Northern district.

The costliest of them all was the HK$90.7 billion Sha Tin-Central line, which opened in mid-May as the East Rail line extension to Admiralty. In comparison, the high speed rail line connecting Hong Kong and the mainland cost HK$84.4 billion.

The MTR’s local network, which carried 812 million passengers in 1997 carried 1.4 billion last year.

Thanks to a fare adjustment mechanism adopted 12 years ago, rail fare increases have been regulated to stay in line with inflation. An adult travelling by MTR from Tsuen Wan to Admiralty pays HK$15.50 now, 32 per cent more than HK$11.7 in 1997.

The high-speed cross-border rail from Guangdong province to the West Kowloon terminus, cut travelling time to 19 minutes to Shenzhen and 47 minutes to Guangzhou.

The Hong Kong-Zhuhai-Macau Bridge, which opened in 2018 and shortened cross-border travel times by road, cost HK$120 billion and took nine years to complete. Other overland connections include the Hong Kong-Shenzhen Western Corridor and the Liantang/Heung Yuen Wai Border Crossing.

4. How safe is Hong Kong?

The overall crime rate in Hong Kong saw a notable decrease until the social unrest of 2019 saw widespread clashes between protesters and frontline police. While the number of “hard” crimes declined sharply, the increasing use of technology saw more Hongkongers falling victim to online fraudsters.

Between 1997 and 2021, the number of robbery cases fell from 2,914 to 123, while burglary cases slid from about 6,400 to 1,472.

The number of severe violent crimes also fell in the past 25 years. Murder cases dropped from 102 in 1997 to 23 last year, while wounding and serious assault cases went down from nearly 7,000 to around 4,000. Sex crime cases went down slightly from 1,188 to 1,097.

Triad-related crime dropped by nearly 30 per cent from 2,599 cases in 1997 to 1,888 last year.

Soon after Hong Kong returned to China, several high-profile armed robberies and kidnappings occurred. Notorious gangster “Big Spender” Cheung Tsz-keung kidnapped property tycoon Walter Kwok Ping-sheung, then-chairman of Sun Hung Kai Properties, in 1997.

Cheung was arrested and executed on the mainland in 1998. There have been no high-profile kidnapping cases since.

In 1998, “King of Thieves” Kwai Ping-hung hit two shops in Causeway Bay and escaped with more than HK$3 million in watches and jewellery. He was arrested in 2003, jailed and released earlier this year.

More recent years have seen a sharp rise in telephone scams and cybercrime. Between 2005 and 2021, more than 11,100 people in Hong Kong lost a total of HK$1.8 billion in scams involving confidence tricksters operating easily across borders.

The victims have included women and men scammed by sweet-talking “online lovers” they never met, individuals frightened into believing they had run foul of the law in mainland China, and families tricked into paying to get a family member out of trouble.

After the handover, Hong Kong allowed citizens to express their views in public gatherings, processions and demonstrations. From barely around 1,000 “public order events” a year during the colonial era, all with police approval, the number rose to 3,824 in 2007, 11,811 in 2017, and 20,859 last year.

On July 1, 2003, an estimated crowd of 500,000 took to the streets, resulting in the government shelving its plan to enact national security legislation required under the Basic Law, the city’s mini constitution.

The Occupy pro-democracy protests of 2014 shut down parts of the city for 79 days. Then, in 2019, there were months of anti-government protests over an extradition bill which would have allowed fugitives to be sent to the mainland, with violent clashes between demonstrators and the police.

In June 2020, Beijing imposed the national security law banning acts of secession, subversion, terrorism and collusion with foreign forces. Dozens of political and civil society groups disbanded, and more than 100 opposition politicians, civil society activists and journalists and media owners were arrested.

5. Have public and cultural spaces improved?

Despite intensive urban development, Hong Kong has kept most of its country parks intact. They account for 40 per cent of the city’s 1,113.76 sq km (430 square mile) land area and drew 12.4 million visitors last year.

There are 24 country parks, six marine parks and one marine reserve. Robin’s Nest in Sha Tau Kok has been approved to be the city’s 25th country park and the South Lantau marine park will be the seventh and largest marine park.

In heritage conservation, a government scheme has engaged the private sector to turn more than 20 disused historic sites into new cultural spaces.

Lui Seng Chun, a pre-war era Chinese-style shophouse in Mong Kok, has been converted into a Chinese medicine healthcare centre, while Mei Ho House, the last surviving building of the city’s first public housing estate in Shek Kip Mei, is now a youth hostel.

The city’s largest conservation project since the handover was the transformation of the former Central Police Station compound into the Tai Kwun culture venue by the Jockey Club. Completed in 2018, it now houses a museum and exhibition and event spaces.

A continuous public promenade being built around Victoria Harbour has opened new space for relaxation, jogging and other leisure activities and is expected to reach 34km by 2028.

Academic Sampson Wong from Chinese University said the improvement of public spaces must go beyond providing designated public areas, as the value of these spaces depends on how residents use and enjoy them.

“It’s about letting people know that this space is theirs, they have ownership and can explore how to use it. If a house is yours, you will be thinking about how to use it well,” Wong said.

6. Is the air cleaner?

Annual average concentrations of most major pollutants have been decreasing over the past seven years, a Post analysis of government data on air quality in roadside and general stations found.

One indication is the annual average of respirable suspended particulates (PM10), which include smoke, dust and other tiny matter in the air. Data from the Central and Western district air monitoring station showed 25 micrograms per cubic metre in 2020 half the annual limit of 50 micrograms and 51 per cent lower than the 1997 average.

Among all pollutants, the decrease in sulphur dioxide was most pronounced. The annual average concentration of the chemical in various districts dropped by 60 per cent from 2013 to 2020, according to green group Clean Air Network.

The improvement is attributed to various policies tackling vehicle emissions, a major cause of air pollution in Hong Kong.

The government introduced a fine on idling motor vehicle engines in 2011 and began phasing out diesel vehicles by subsidising owners to switch to cleaner models in 2018. Subsidies for electric vehicles were introduced last year.

The decline of manufacturing activity in southern mainland China since the early 2010s has also helped, with fewer pollutants blowing into Hong Kong from there.

7. How does Hong Kong care for minorities?

The city is home to about 580,000 non-Chinese residents from minority groups who make up 8 per cent of the population, according to the 2016 census. Filipino and Indonesian foreign domestic workers make up 57.7 per cent of Hong Kong’s ethnic minority population.

Those who have settled in the city for generations include many of South Asian origin, from countries like India, Pakistan and Nepal. Hong Kong’s ethnic minority groups have faced challenges in education, disadvantaged by their lack of knowledge of Chinese, and many are trapped in low-paying jobs.

The Race Discrimination Ordinance, in effect since 2009, remains the main legal protection for these residents. Complaints can be made to the Equal Opportunities Commission, which will investigate, mediate between parties or offer legal help for the complaint to go to court. There have been only three such court cases so far.

Prejudice and discrimination persist. A 2016 survey by the commission found that just over half the ethnic minority respondents said they had not experienced discrimination in their daily lives.

Phyllis Cheung, chief executive officer of Hong Kong Unison, an NGO helping ethnic minority groups, said current laws do not go far enough. “Stereotypes of ethnic minorities continue to perpetuate and materialise into explicit and unconscious racial bias and discriminatory treatment,” she said.

There are also anti-discrimination laws covering sex, family care responsibilities and disability. Those from sexual minorities have complained of inadequate protection.

Individuals from the city’s LGBT+ community have gone to court and persuaded the city’s judges to grant same-sex partners spousal benefits, custody rights and equal rights in home ownership. But the judges have been unmoved on recognising same-sex unions in Hong Kong.

“Judicial review and case law can provide guidance and be used to educate people on human rights but have their limits. Judges cannot draft the legislation necessary to protect these groups,” said human rights lawyer Mark Daly, who has been involved in landmark legal victories for equal rights.