The battle over Hong Kong’s controversial small-house policy is not finished

- The High Court has upheld the right of indigenous male villagers to build homes on private land

- But few were satisfied by the judgment, with challenges and policy headaches still to come

A recent court decision on a controversial policy affecting New Territories villagers has reminded Hongkongers that when it comes to housing, as in so many other areas of life, people are born unequal.

While most of the city struggles with astronomical property prices for tiny homes and a severe shortage of land for new developments, it is a different story for males over 18 years old who can prove their forefathers lived in rural villages more than a century ago.

Thanks to a colonial-era law, these males – known as ding – are allowed to build “small houses” on their farmland without paying a hefty fee that reflects the value of the property after development.

By forking out about HK$5 million (US$637,500) to erect and furnish a three-storey house of up to 2,100 sq ft — a spacious home by Hong Kong standards — they can own a property easily worth HK$20 million or more.

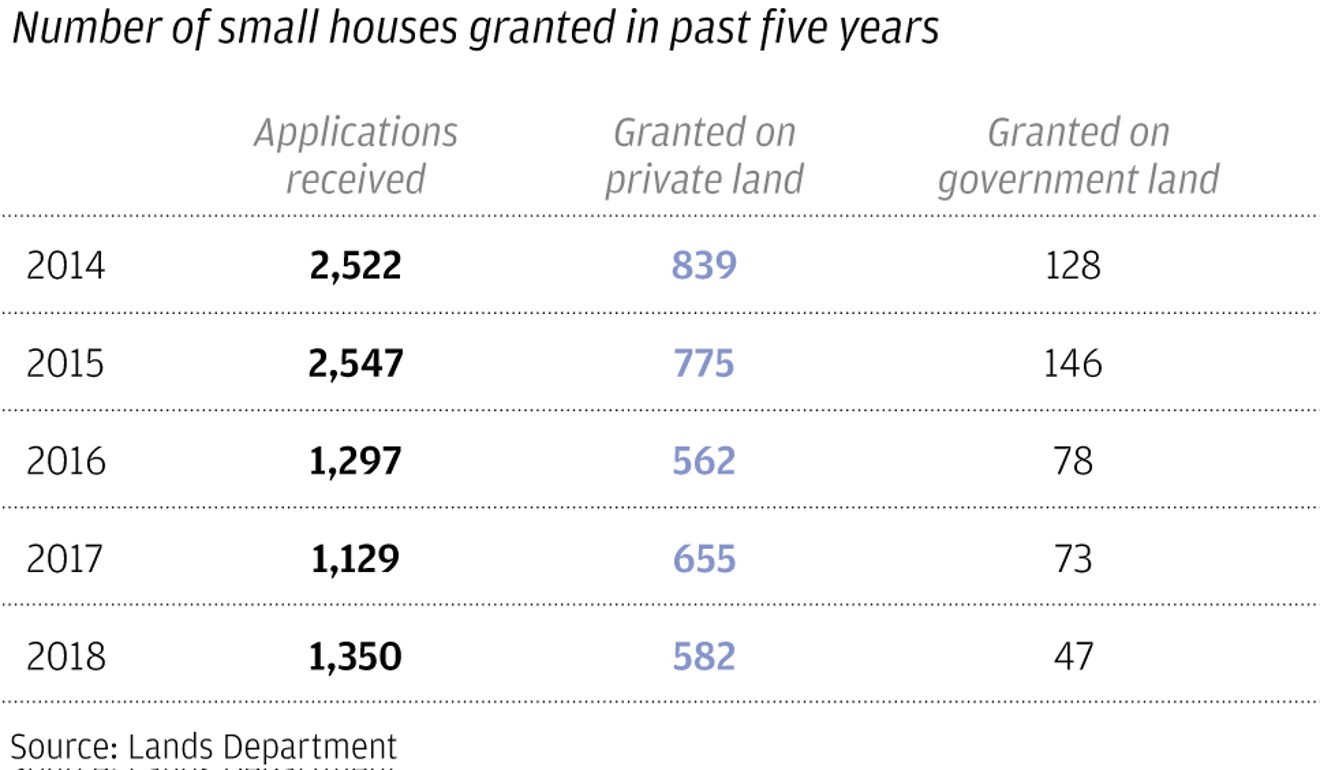

Since their introduction in 1972, the so-called ding rights have resulted in 43,000 such houses being built across the rural New Territories. In a city starved of space, some 5,000 hectares – almost a fifth of the size of Hong Kong’s urban areas – are locked up for such low-rise development.

Mr Justice Anderson Chow Ka-ming confirmed that the privilege was a constitutionally protected “lawful traditional right” of indigenous villagers, as protected by the Basic Law, the city’s mini-constitution, and this right goes all the way back to 1898, the year the British took over the New Territories.

Significantly, he ruled that the privilege applied only to private land. About a third of the existing small houses are built on public lots. The ruling left about 2,000 villagers’ applications to build on public land in limbo.

The small-house policy is against human rights and the interests of the majority of the people. All people should be equal. But now we are not

Upset by the outcome, powerful rural leaders who represent indigenous villagers’ interests organised a demonstration.

These rural strongmen have curried favour with the Chinese central government over time and they have threatened to ask Beijing to override Chow’s ruling if Hong Kong’s top appellate court fails to overturn it.

City dwellers, who have long regarded the villagers’ privilege as unfair and open to abuse, also want to see an appeal and have criticised Chow for failing to address the discrimination entrenched in the policy.

It is understood that the two men who sought the judicial review in the first place, former civil servant Kwok Cheuk-kin and social worker Hendrick Lui Chi-hang, intend to appeal against the judgment too, because they want the policy abolished on equality grounds.

“The small-house policy is against human rights and the interests of the majority of the people,” said Lee Wing-tat, a former lawmaker specialising in land policy, who now leads the think tank Land Watch. “All people should be equal. But now we are not.”

The rural power is offended

Leading the protests against the ruling is the powerful Heung Yee Kuk, a legally recognised body representing indigenous villagers and influential in swaying the government’s handling of rural affairs. It invited about 1,000 villagers to its Sha Tin headquarters on Tuesday to express their concerns.

“It is for villagers to vent their anger preliminarily and express their concerns in a rational way,” said Leung Fuk-yuen, a vice-chairman of the kuk’s land development, planning and conservation committee.

The kuk has proven ability in mobilising villagers. In 2011, when the government tried to get tough on illegal structures in village houses, it organised a protest during which villagers staged a mock funeral for then secretary for development Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor – now Hong Kong’s chief executive – and burned an effigy with her name stamped on it.

A source said the kuk planned to fight the ruling “at all costs”, after spending HK$30 million on the first round of the judicial review.

Two village land projects suspended after small-house policy ruling

Alfred Lam Kwok-cheong, a solicitor and an ex officio member of the kuk, said it was very likely to appeal, and its main argument turned on the fact that the Basic Law was established in 1990 and took effect when Hong Kong was handed back to China in 1997.

It saw no need to look earlier than 1990 to decide if villagers can build on government land, he said, and the kuk would contest Chow’s ruling that the small-house policy applied only to private land.

Also crying foul are residents from three villages in Sha Tin and Yuen Long who gave up their land more than two decades ago under a special government scheme to consolidate planning and redistribution of village land for building small houses.

Officials put the scheme on hold in 1999, citing the need to review the small-house policy. The recent court ruling will enable officials to end the scheme as the acquired land is now considered public.

“If building on public land has been ruled unconstitutional, there should be another judicial review to decide if the government’s acquisition of villagers’ land was constitutional,” said Lam Kwok-yin, 68, a former chief of Pai Tau, one of the three affected villages.

These villagers are considering suing the government for taking away their land and being sluggish in carrying out the scheme as planned.

The rise of a ‘divisive policy’

There are 642 recognised villages today, but officials have no estimate of the number of males who can claim ding rights.

Sociologist Lau Siu-kai says Article 40 of the Basic Law, which safeguards the rights of indigenous villagers, was incorporated because the kuk and the villagers supported Hong Kong’s return to China in the 1980s, at a time when many in the city had grave doubts about communist rule.

“It was a divisive policy devised by the colonial government,” Lau said. “People are now asking how come we still need to keep such a colonial-era policy so long after Hong Kong’s return to China.”

He noted that successive administrations since 1997 had avoided taking a tough stance against the villagers, long regarded as an “organised minority”, or the kuk.

It was a divisive policy devised by the colonial government. People are now asking how come we still need to keep such a colonial-era policy so long after Hong Kong’s return to China

The British never forgot the villagers’ bitter armed resistance in 1898 against the takeover of the New Territories. More than half a century later, they were grateful for the kuk’s strong support when the colonial government suppressed riots instigated by the pro-communist camp in 1967.

Successive administrations have also relied on the kuk’s support in acquiring rural land for various new-town and infrastructure projects over the decades.

When she was development secretary in 2012, Carrie Lam told the Post she was mulling ending the small-house policy, but quickly backed off after a backlash from the kuk.

Lee of Land Watch believed the kuk’s close ties with Beijing and the government’s reliance on the powerful group in political and development issues may have put pressure on officials.

“When the country people get angry, the kuk can mobilise tens of thousands of people to march and protest, on a scale that can rival any marches organised by pro-democracy parties,” he said. That prospect could worry Beijing, which prefers to keep Hong Kong stable, he added.

A way to end abuses?

For all the talk about protecting the rights of indigenous villagers, the small-house policy has also been subject to rampant abuse, by villagers as well as developers.

The Lands Department received about 1,500 complaints of suspected abuse from 2016 to last year. So far, 133 cases are under criminal investigation.

Eligible male villagers cannot sell their building rights, but they are free to sell the small houses they build after paying the land fee they had been exempted from earlier.

Developers holding large rural land banks have been known to enter into secret deals with eligible ding villagers, including many who have no land or may even have migrated, to game the system.

Typically, the developers pay willing men to go along with a scam to apply to build small houses on land owned by the developers, not the villagers.

Once the applications are approved, the developers build the small houses, pay the land fees and then sell the properties for huge profits.

In 2015, a developer and 11 villagers were each jailed for up to three years for cheating the system this way.

More recently, a luxury housing estate in Tuen Mun comprising 28 small houses was found to have been built by a single developer representing 28 male villagers, including 17 Malaysians.

The recent court ruling might provide a way to tackle abuses, said Roger Nissim, a former senior official in the Lands Department.

The judge said there was no dispute over the fact that male villagers were only allowed to build houses for their own use or the use of their families. Based on that, Nissim said, the government could now ban the sale of small houses.

“The small-house policy isn’t going to be airbrushed out of existence. It’s very entrenched,” he said. “What you’ve got to stop is the speculative element.” However, he did not think the government had “the guts” to proceed.

Beijing to the rescue?

Well aware of their political clout, some rural leaders have threatened to take the matter all the way to Beijing if legal action fails.

The kuk’s Leung Fuk-yuen has suggested asking Beijing to interpret the Basic Law and override the Hong Kong courts.

But Johannes Chan Man-mun, a former law dean of the University of Hong Kong, warned that the case is “entirely a domestic matter”, and the national legislature should refrain from making any interpretation of Hong Kong’s law under the principle of “one country, two systems”.

He said that while there was no doubt that the ding rights policy was discriminatory, the Basic Law’s protection of villagers’ traditional rights trumped other clauses about equality and human rights. “A specific clause always overrides a general one,” he said.

As for banning the sale of small houses to prevent abuse of the system, Chan pointed out that villagers were free to sell their property before 1898, so if the courts now recognise their right to build on private land, their right to sell their property is also protected.

Sociologist Lau did not think the kuk would ask Beijing to step in. “The central government would offend the majority of Hong Kong people if it rules in favour of the indigenous villagers,” he said.

A step closer to the end of policy?

Land Watch’s Lee said the recent judgment would have an impact on ding rights because the government may decide it no longer needs to set aside land for future generations of indigenous villagers who want to build small houses.

A 2013 study by the think tank Civic Exchange found about 400 hectares of private land available for small houses in village areas. Since then, the government has stopped releasing updates on available land.

Lee expected that the government would stop swapping or granting public land to villagers. “Now the policy will die a gradual death,” he said.

Lawyer Maria Tam Wai-chu, a long-time lawmaker and member of the drafting committee for the Basic Law, said that when the drafters mulled over safeguarding the rights of indigenous villagers more than two decades ago, they expected the small-house issue to gradually diminish in importance.

Once villagers used up their lots and were unable to swap land with the government, the drafters expected that small houses would gradually become a thing of the past, she said.

“We wanted to allow this issue to disappear over time instead of taking the right away,” Tam recalled.

But Brian Wong Shiu-hung, a full-time researcher of concern group Liber Research Community, said it was too early to say what would happen next with the policy and villagers who want to build small houses.

He pointed out that the government had been zoning more land for village development each year, and it included both public and private lots. If this expansion continues, the villagers’ private land bank will grow.

Government data shows that between 2008 and 2017 Hong Kong’s village areas grew by 7 per cent, or 223 hectares, but there is no indication of the public and private proportions. The Development Bureau would only say that the increase mainly reflected the inclusion of villages previously not covered by official zoning plans.

“I won’t hold my breath,” Wong said. “I think it’s wishful thinking that the policy will come to an end.”

Additional reporting by Naomi Ng