1 in 5 arrests by Hong Kong’s national security police made under colonial-era sedition offence instead of 4 crimes laid out in Beijing-imposed law

- Growing trend in use of sedition charges in recent months, with allegations centred on list of acts and speech deemed problematic

- Authorities use sweeping powers under national security legislation to enforce sedition law, which has low threshold for arrest and lighter jail terms for convictions

There has also been a growing trend of sedition charges used in recent months, with allegations centred on a list of acts and speech deemed problematic by authorities.

Police investigating sedition offences have recourse to many of the same powers conferred on them by the national security law. Officers have the same lower threshold of evidence they must meet to conduct raids, and they have the power to seize a suspect’s passport without judicial approval, while the accused face a higher standard in obtaining bail.

But the penalties imposed on the convicted are vastly different: sedition under the Crimes Ordinance carries a maximum sentence of two years in jail for a first offence, and three years for a subsequent one, while national security offenders can be imprisoned for life.

Legal experts cautioned that the frequent application of the sedition law could erode free speech, and it was disproportionate to apply the standards of the national security law to suspects accused of the lesser charge.

Hong Kong police arrest owners of Taiwanese drinks shop over social media posts

Police told the Post they had arrested 201 individuals, 155 men and 46 women aged between 15 and 90, for allegedly endangering national security as of last Thursday, as Hong Kong marked two years since the law was implemented on June 30, 2020. The police’s National Security Department has been the lead enforcer.

A total of 125 individuals and five companies were charged in the cases concerned, according to the Security Bureau, while all of the 12 suspects whose cases went to trial and were concluded have been convicted.

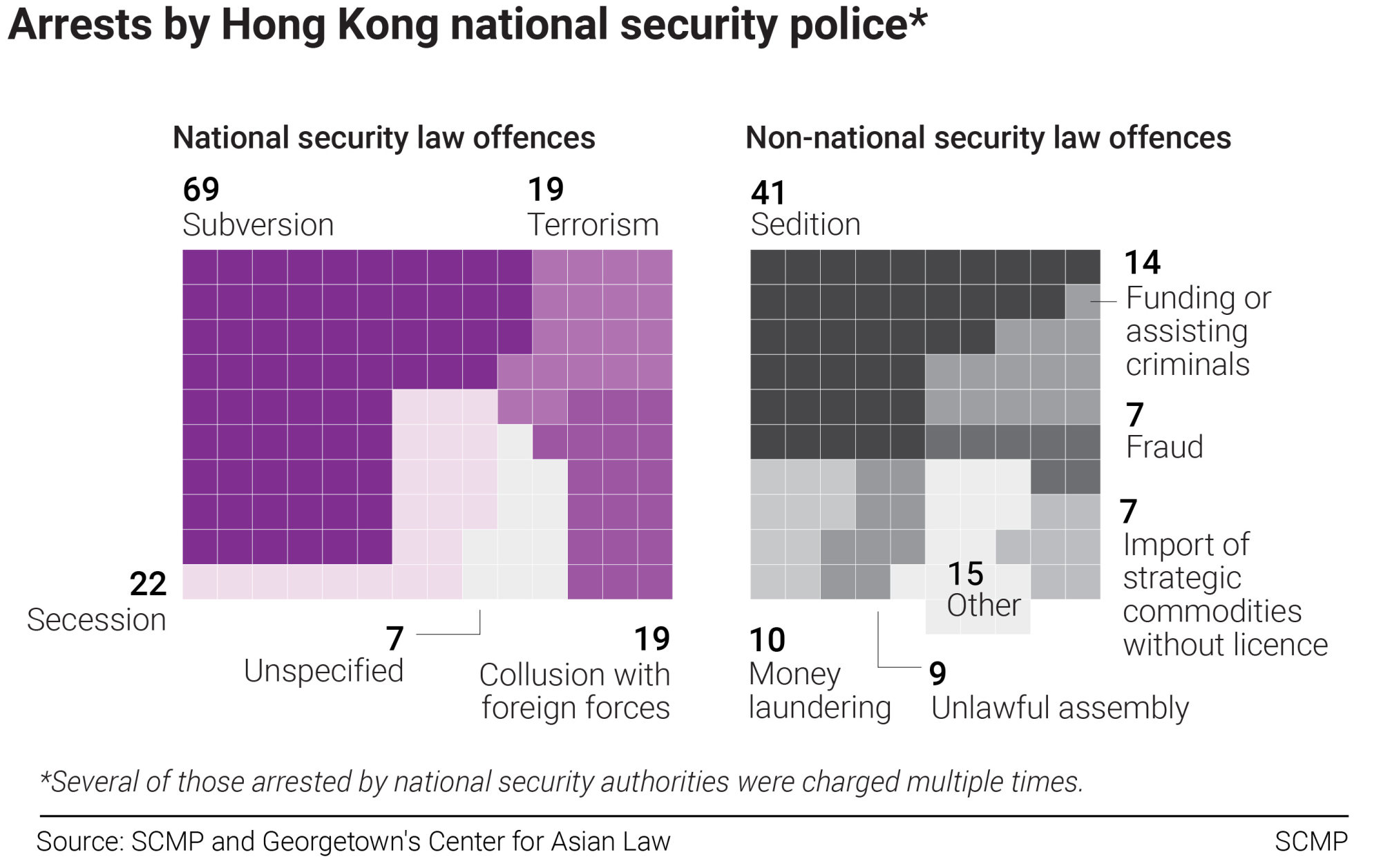

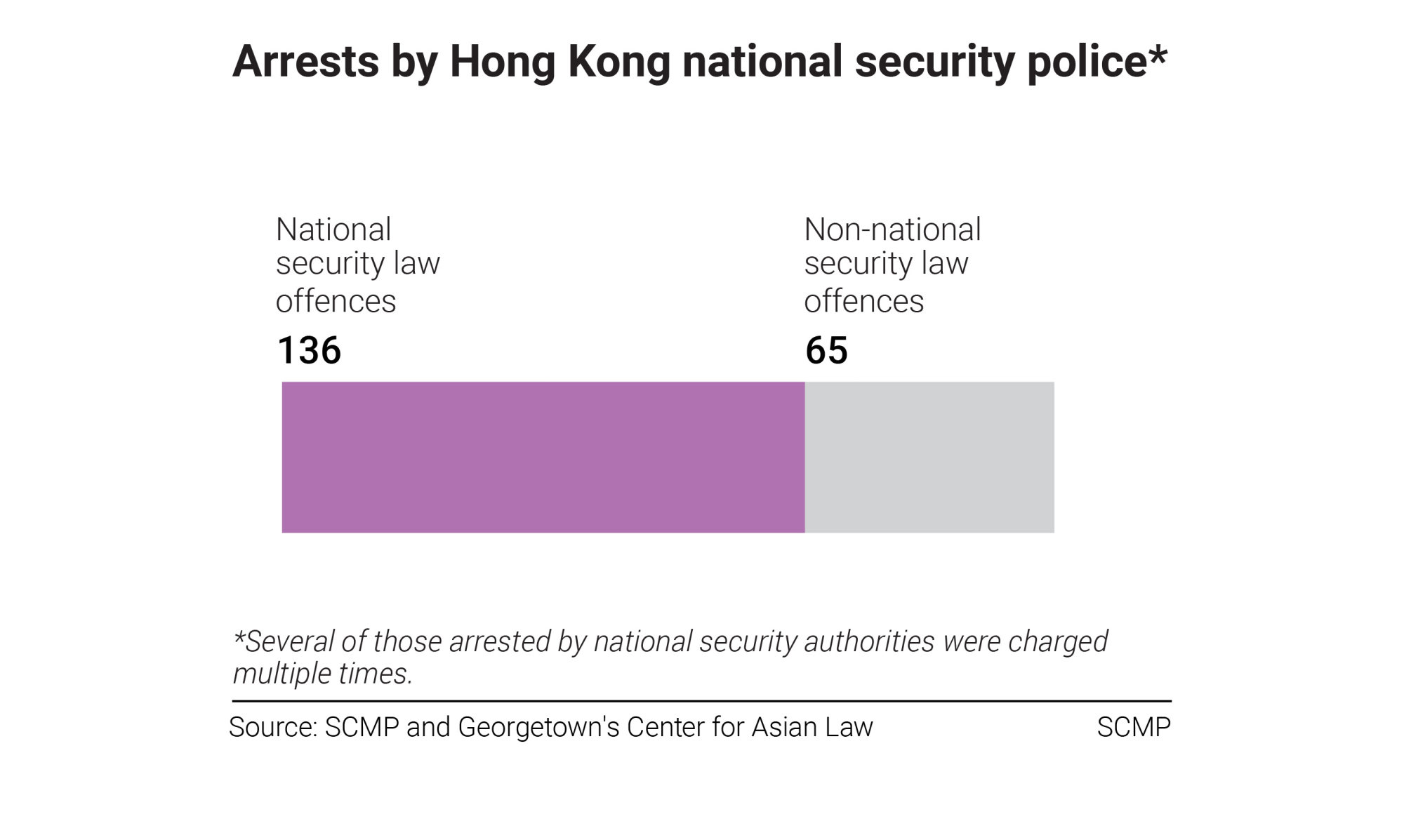

A closer look at each of the police operations with reference to data compiled by the Georgetown Center for Asian Law revealed that up to 136 arrests were made under the four offences covered by the national security law – secession, subversion, collusion with foreign forces and terrorism – making up 67.7 per cent of the total.

The rest were on the grounds of offences not part of the Beijing-imposed legislation.

A third of arrests were made in the second year since the law took effect, while half of the total arrests involved activists, politicians or members of political groups.

The largest operation so far has been the arrest of 53 opposition activists on January 6, 2021, for their alleged role in organising an unofficial primary election, making subversion the most frequently cited offence under the national security law. It was raised as justification for 69 of the arrests, or 34.3 per cent, with most suspects being refused bail before trial.

The remaining three offences stipulated in the national security law have been less frequently cited, with secession taking up 10.9 per cent of total arrests, and terrorism and collusion with foreign forces each at 9.5 per cent.

Hong Kong journalist group insists it operates in accordance with law

Among the arrests conducted by the National Security Department for offences outside the 2020 law, the 41 colonial-era sedition cases made up the largest share, at 20.4 per cent, followed by funding or assisting criminals and money laundering.

Despite the broad scope of the new law, national security authorities have become increasingly reliant on sedition, an offence introduced by the British in 1938 amid a rise in anti-colonial sentiment.

Before the latest slate of arrests, the law was last used to go after pro-Beijing newspapers amid the anti-government riots in 1967.

In the first half of the year, 70 per cent of arrests conducted by the National Security Department were on the grounds of this offence.

A landmark case involved pro-democracy activist Tam Tak-chi, known as “Fast Beat” in his career as a radio DJ, who was the first person to be charged with sedition since 1967. He was sentenced to 40 months behind bars under seven sedition charges for uttering words that prosecutors regarded as “spreading hatred or contempt or excite disaffection against the government” over his role in various public gatherings, some of which took place before the imposition of the national security law.

Tam, who was found guilty over his use of slogans such as “Liberate Hong Kong; revolution of our times,” and “Five demands, not one less”, was not charged with a national security offence, but his case was heard by a judge designated to hear them upon a request by the prosecutor.

In February, singer and activist Tommy Yuen Man-on was arrested by national security police after he made comments on social media that allegedly “vilified” the government’s Covid-19 policies. In the same month, two women were charged with sedition over social media posts urging people not to get coronavirus vaccines and to flout the city’s pandemic-control rules. They were jailed last week for up to seven months.

In April, four men and two women were arrested over “an act or acts with seditious intention to bring hatred or contempt or to excite disaffection against the administration of justice in Hong Kong”.

In the 10 days leading up to the city’s celebrations to mark the 25th anniversary of its return to Chinese rule, seven more arrests under sedition were made, including two men who were accused of making social platform remarks that “promoted feelings of ill will and enmity between different classes of the population of Hong Kong and incited the use of violence”.

Kent Roach, a law professor at the University of Toronto who has compared security laws in different jurisdictions, said sedition offences remained on the books in England, Canada and India, but were not being applied in a similar fashion in Hong Kong.

Roach described colonial sedition offences in both India and Hong Kong as “outdated and vague in their common references to hatred and contempt”, saying the Indian court “rightly recognised” the threat that the law posed to democratic freedoms and unpopular speech.

Where to draw the line? Hong Kong satire from cartoons to internet memes

He referred to a decision by India’s top court in May to suspend the sedition law, saying it was “not in tune with the current social milieu, and was intended for a time when this country was under the colonial regime”.

Michael Davis, a former legal scholar at the University of Hong Kong’s law school, said it was problematic for authorities to connect the sedition offence with the national security law by adopting the latter’s standards on procedural, bail and rights limits.

“This is problematic as international standards in both common law and international practice otherwise would require that such charges involve speech with imminent threats and likelihood of violence, which most of these cases do not,” he said.

Davis, now a global fellow at the Washington-based Wilson Centre, argued that the frequent use of the sedition charge had become a threat to basic rights of free expression. The use of it also allowed police and prosecutors to go after speech that occurred before the enactment of the national security law, he added.

Former Hong Kong director of public prosecutions Grenville Cross said the sedition offence required a higher standard for prosecution to be laid and to succeed, including the secretary for justice’s consent and corroborated testimony from more than one witness.

“If the task of investigators in establishing the crime of sedition has been facilitated in any way, this may worry the culpable, but there is no reason why it should concern those who believe that people who break the law should be held to account,” he said, adding that the offence was “clearly constitutional”.

Hong Kong leader defends police action to close off Victoria Park on June 4

A spokesman for the Security Bureau said the court held that the sedition offence satisfied the “prescribed by law” requirement, and was consistent with the relevant provisions of the Basic Law, which is the city’s mini-constitution, and the Hong Kong Bill of Rights on the protection of human rights.

“Prosecutions would be instituted only if there is sufficient admissible evidence to support a reasonable prospect of conviction and if it is in the public interest to do so,” he added.