Hong Kong needs a whistle-blower law for better governance and business practices, researcher says

I have a friend who protects me from myself. Mark rants every time I want to do something risky. He would rat on me in a second - if I wanted to do something truly unsavory. Mark is my whistle-blower.

All of us have our own Mark - except Hong Kong's government bodies and companies.

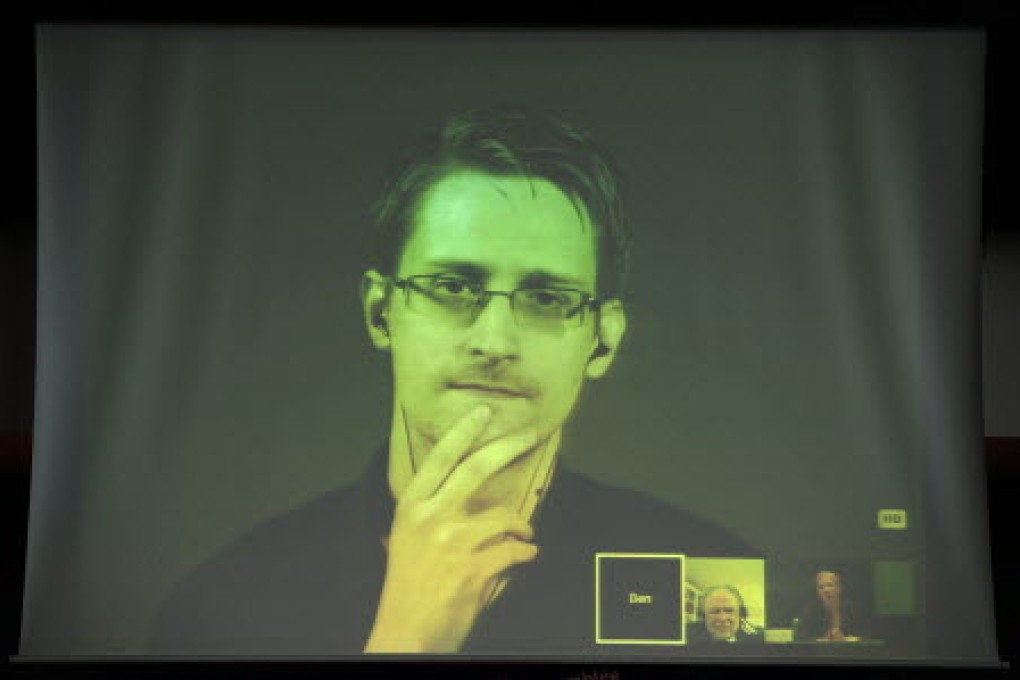

The city has no constitutional jurisprudence encouraging individuals to stand up to wrongdoing and cover-ups. Nor do we have a culture that encourages the Edward Snowdens among us to "do the right thing". Local law has not taken even baby steps to offer the right incentives. Hong Kong needs a whistle-blower law.

Professor Robert Bowen and colleagues at the University of Washington have produced evidence showing whistle-blowing schemes can raise shareholder value and lower social risks. Dated figures from our own studies show many Hong Kong firms still lack whistle-blowing policies. That's why employees "doing the right thing" face retaliation and have higher chances of committing suicide. Would the city have cleaner air, safer workplaces and more profitable investments if we had whistle-blowing laws?

Britain's Public Interest Disclosure Act is a role model that Hong Kong can improve on. It encourages employees to denounce wrongdoing to internal ombudsmen first, and only to the media as a last resort.

The benefits are threefold. First, government agencies and companies could spend less money. Why pay three or four staff members to police the organisation when everyone can do it for free? Second, such rules would encourage investors. If they knew information about their investments' risks could come from anywhere, they would feel more confident investing. Third, these disclosures would advance the work of the media and academics. Imagine if newspapers could warn of problems based on whistle-blower disclosures, or if academics could search through thousands of disclosures, looking for common patterns.