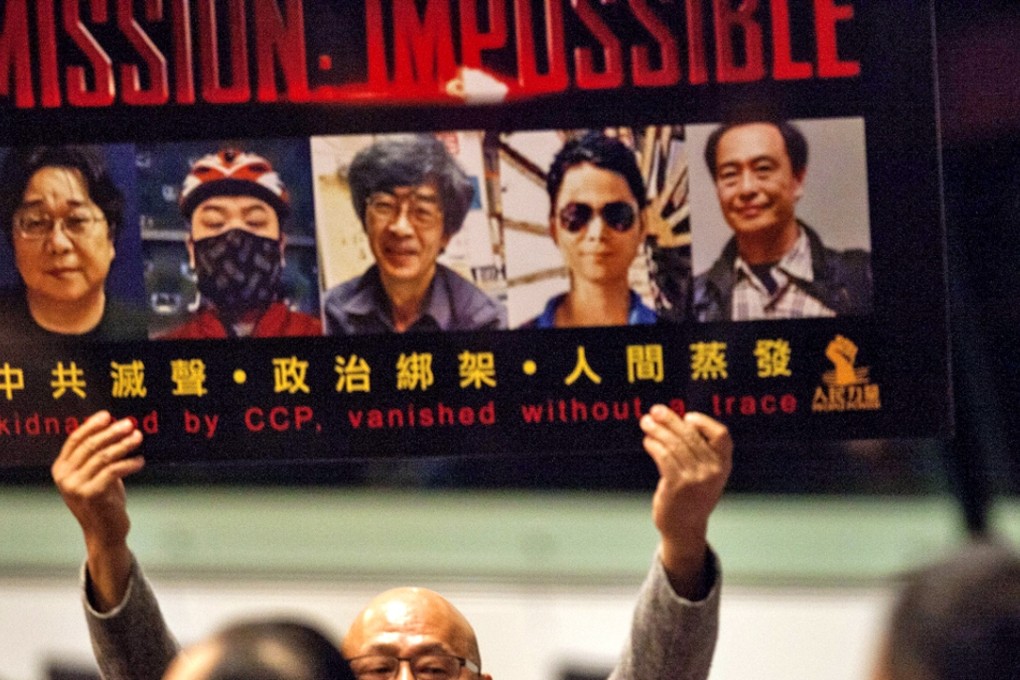

Who believes China’s narrative on Hong Kong’s missing bookseller mystery?

As experts voice their doubts, social media users dole out the scepticism and sarcasm on Gui’s ‘complicated history’ and Lee Bo’s televised ‘confession’

A rapid succession of letters, calls and a televised confession from Hong Kong’s missing booksellers have raised more questions than answers for sceptical experts and citizens alike.

“He also has many facades that I do not know ... He is a morally unacceptable person. This time he has caused me trouble.”

It was the third letter alleged to have been sent from Lee Bo to his wife in Hong Kong, following two earlier missives.

The letter told his wife he was in mainland China voluntarily helping authorities with an investigation, as well as asking international authorities to leave him alone, and Hongkongers to not protest in his name.

READ MORE: Experts sceptical at Gui Minhai’s ‘illogical’ surrender

Shortly after Gui’s public confession to a drunk driving accident in 2003 and admission that he had absconded from the conditions of a suspended sentence, his daughter received a message from him on Skype telling her not to worry and “please keep quiet.”