Letter of the Law: The fine line in Hong Kong between freedom of speech and national security

In conflicting legal arguments, advocates of freedom of speech seem to have a stronger case, but don’t discount national security

“I want real universal suffrage.” Is the phrase protected speech under the Basic Law? Does police discouragement of hanging the banner represent an un-Basic-Lawable (as the word unconstitutional clearly doesn’t apply) “restriction of freedom”? Or do hikers putting banners on Lion Rock pose a threat to national security? In short, the answer is both.

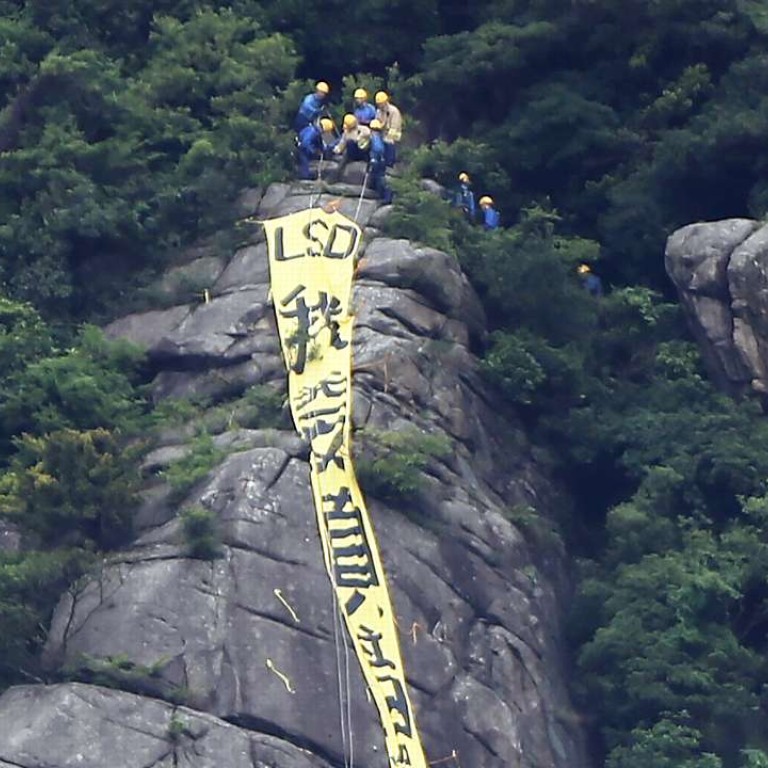

The police camped near Lion Rock in an attempt to dissuade activists from putting up the same banner they put up during the umbrella movement. They failed. The banner went up on nearby Beacon Hill.

According to press accounts, the police claimed to act in the interests of national security. They also probably wanted to protect the nation’s security as well.

What does Hong Kong’s emerging jurisprudence tell us about the legality of both the protesters’ and police’s actions?

Advocates of freedom of speech seem to have a stronger legal case. Article 27 of the Basic Law provides unequivocally for freedom of speech. Nowhere does the article provide for “freedom of speech, except when Zhang Dejiang comes to town.” The banner is clearly speech. If the League of Social Democrats allies who eventually put up the banner had a quasi-religious belief in their views, one might half-jokingly argue that Article 32 applies (protecting freedom of conscience). Yet, we don’t have the right to free speech. Indeed, few countries around the world recognise speech as a natural right.

Don’t-rock-the-boat advocates might rightly argue that national security trumps all other values – if not in theory, then in practice. Inter arma enim silent leges (in times of war, the law falls silent). Laws don’t apply when people start seriously whacking each other. Article 14 allows the government to keep “public order”. How does a banner pose a threat to national security?

Protesters are far more likely to break windows in order to support the activists than to ban them.

An economist would argue that the police actions on that Tuesday saved an expected value of 300,000 lives. Expected value? Expected value represents the way we think about necronomics – or the economics of death. Imagine the banner increased the probability of another Cultural Revolution from 0 per cent to 1 per cent. Imagine also that such a conflict would cost 30 million lives (or more, just like last time). Thus, hanging the banner on average should cost 1 per cent of those 30 million lives, or 300,000 souls. That yellow banner doesn’t look covered in blood.

Even the first-year undergraduate knows that the main motivation for Chinese/Communist Party policy rests in preventing the mass killings of the middle to late 20th century.

Most governments follow something called the precautionary principle. In layman’s language, the principle says government should not allow anything that might cause something catastrophically bad, even if that thing has microscopic, minuscule odds of happening.

Today’s free speech on Beacon Hill could be tomorrow’s revolt in Xinjiang. Yet, the lack of it is what allows protesters to disappear in Xinjiang.

Dr Bryane Michael is a senior fellow with the University of Hong Kong’s Asian Institute for International Financial Law (AIIFL)