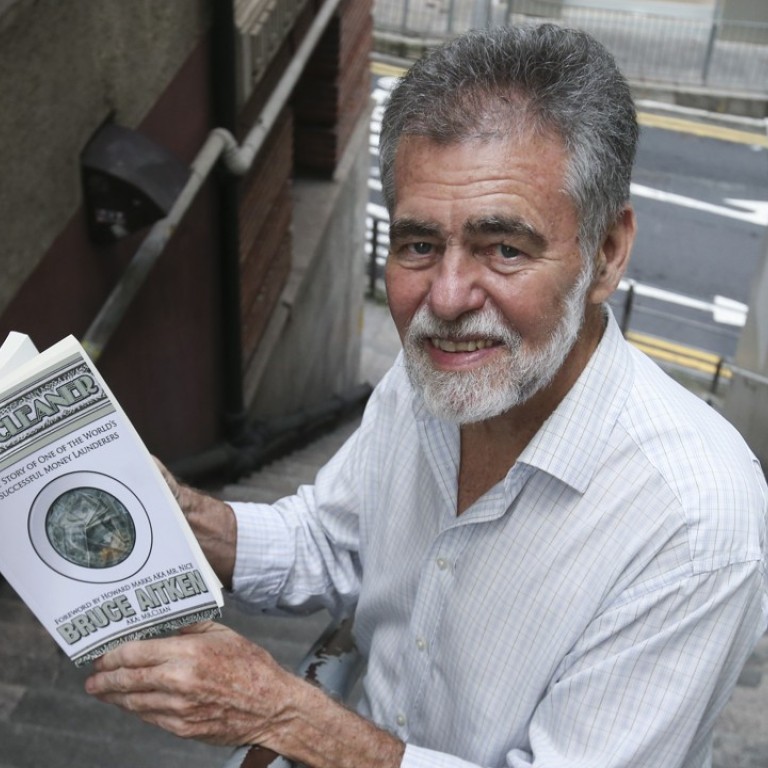

Former money launderer Mr Clean tells of Spanish priest agent, snitches, drug lords and stashing cash in Hong Kong

Bruce Aitken recalls how back in the day, he would get the red-carpet treatment in banks, no questions asked, if he walked in with a wad of cash

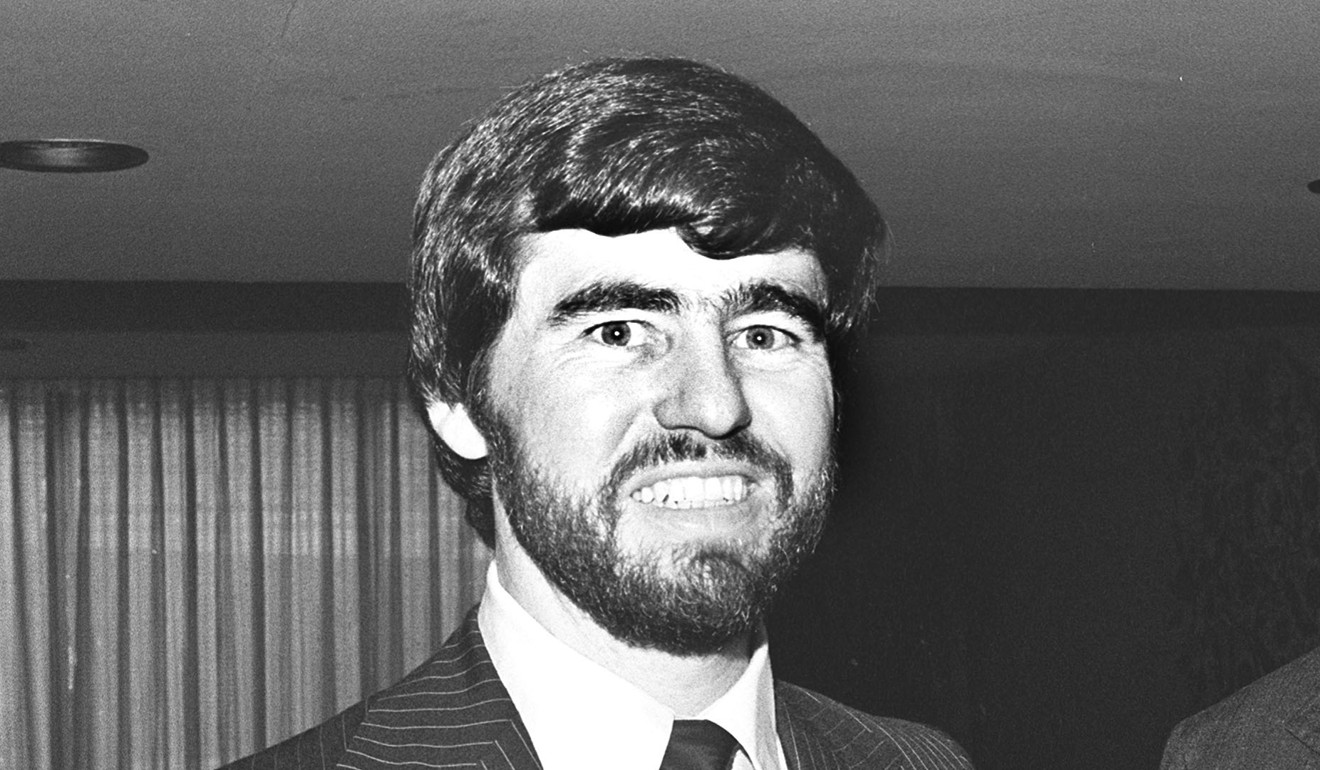

Bruce Aitken, aka Mr Clean, learned about the black currency market as a bloody war was unfolding. It was the 1970s, and he was working for American Express in military bases across Vietnam.

It did not take him long to realise he could create money out of thin air in the war-torn Southeast Asian nation, he said.

But it was in Hong Kong where he later perfected the art of “cleaning money”.

Now aged 72, Aitken has told his story in his book titled The Cleaner.

Chance and circumstance, he said, made him grow into one of the world’s most successful money launderers, moving tens of millions of dollars for organisations such as the CIA, government officials and some of the world’s richest drug lords.

Born to an Irish family in New Jersey, US, Aitken graduated in economics and political science in 1967. He was about to sign a contract as a professional baseball player when his life took an unexpected turn.

“I suffered a knee injury. I didn’t have the insurance or funds for an operation, so I had to get a job ... I answered an ad in a newspaper and joined American Express in Vietnam,” Aitken recalled.

“In one weekend I was protesting the war in Vietnam and the next weekend I took a job there, because it was a high-paying job.”

At the time, there were three currencies in Vietnam: the US dollar, which was technically illegal to possess, MPC – military payment certificate – which was used at military bases, and the Vietnamese piasters.

“We were indoctrinated and told never to [exchange US dollars] on the black market, because the money would be going to the Viet Cong [who were fighting against the Americans].

“After I got there, it did not take long to learn that American money was actually going to Vietnamese and Chinese businessmen with accounts in Hong Kong, or traders,” he said.

The official exchange rate was US$1 to 118 Vietnam piasters at the bank. But Aitken soon realised he could take that same US$1 to a Chinese money exchange at the top of the Astor hotel and get 800 piasters.

“I became like the Federal Reserve, creating money out of thin air,” he said.

“I wasn’t gritty. I did this to make some extra dollars. I could have made much more money, but I was young and I believed in America,” he recalled.

As part of his job as bank manager, Aitken would come to Hong Kong every three or four months to bring computer records to American Express offices in the city.

While in town, he would get US$1,000 or US$2,000 in hundred-dollar bills, put them inside Colgate toothpaste tubes and smuggle them back to Vietnam.

“Then, US$1,000 dollars would be $2,000 MPC,” he recalled.

The money was bought at a company named Deak-Perera Far East Limited, which had a big office on Queens Road in Central that Aitken would later join.

After three years in Vietnam, Aitken decided to do law school in the US and marry his Hong Kong-born wife. But he soon started missing the adventures in Asia.

That was when he joined notorious currency trading firm Deak & Company, which would become known for its black market transactions.

Deak & Company was founded in 1939 by a Hungarian man named Nicholas Deak, who was a former agent of the US Office of Strategic Services – the predecessor of the CIA.

Aitken started off based in New York, then headed to Guam and later Hong Kong.

He set up offices all around the world. The one in Central had counters for proper money exchange opened to the public and travel agents, but the real deals were made behind closed doors.

“In those days, there were foreign exchange regulations in all the countries around this region – India, Japan, Philippines, Australia, Korea – but we found ways to break or violate them. That was our main business,” Aitken said.

“For example, we made payments to Japan – millions in yen – smuggling this in specialised golf bags. I would give the money to our agent, who was a Spanish priest,” he said. “There were no records. It was all cash.”

One golf bag would carry about US$500,000 worth of yen.

According to Aitken, these payments were responsible for the Lockheed bribery scandals, which included a string of illicit payments between the late 1950s and 1970s, and involved the US firm Lockheed and the sale of an aircraft to Japan. He said the US consulate in Hong Kong was giving the orders.

“We would get lots of orders. This was just another transaction to us. It was from the CIA. We made the payment to the Lockheed vice-president and somehow the money ended up in the Japanese prime minister’s hands,” he said.

Then Japanese prime minister, Kakuei Tanaka, was forced to resign after the scandal broke.

“We never asked questions about our clients. Every client was the same. You have cash, we buy it,” Aitken said.

He described the company he worked for as the “Rolls-Royce of the black market”.

“There were people doing it cheaper, but with Deak you knew you would get paid and nobody in your country would know you did it ... This service was in demand by governments, stock brokers, bankers, drug dealers … mainly by people who wanted secrecy,” Aitken said.

The company also ran bank accounts in places like Switzerland and Hong Kong.

Deak’s firm would take care of people’s money in exchange for a 3 to 5 per cent commission.

Over the years, Aitken was embroiled in other scandals, including the drug dealing case known as “Cessna-Milner affair” in 1979 in Australia. The syndicate used Deak to send its drug profits from Australia back to Southeast Asia.

Aitken eventually left the company and set up his own business in 1980 – initially working as an outside agent for Deak.

Just a few years later, Deak & Company went bankrupt and in 1985, the company’s founder was murdered in his office.

“Some of the clients left Deak because of the bankruptcy and came to me. Out of my 200 clients, I think the top six were marijuana smugglers, including Howard Marks [known as Mr Nice],” he said.

Aitken’s company, named First Financial Services Limited, was smuggling money to Japan, Australia, US, Korea, Taiwan, India, Russia and African countries.

“I became well-known … But eventually government snitches came to my office, recorded conversations and some of my clients were indicted … Some of the shipments were caught,” he said.

In June 1989 – a time when Aitken was considering retirement – the US government revoked his passport while he was on a business trip to Thailand. Authorities then flew him back to America to face two sets of charges – in Seattle and Nevada – for offences including money laundering and racketeering among others. Each carried up to 20 years in jail.

The case in Seattle was dropped and Aitken was released on a plea bargain after serving a year. “My clients were [severely] sentenced with big fines ... But I served one year and then had four years of unsupervised probation,” he recalled.

“I was out and back home in Hong Kong with a new passport in 1990. But my business, of course, was finished.”

The following decade for Aitken was spent between Hong Kong and Vietnam, where he organised several international events.

More recently, Aitken turned to Catholicism, and in 2004, launched a radio programme for prisoners called the Hour of Love. Since then, he has aired messages from relatives of those in prison every Sunday evening.

He said the royalties from the sale of the book – which includes a foreword written by Mr Nice, who passed away last year – would be used to support him in retirement and also to keep the radio programme going.

“In a way, the radio programme is a bit of a penitence for me. I am trying my best to live a better life and make up for a lifetime of sins,” he said.

Looking back, Aitken said Hong Kong was “perfect” to launder money. “When the US started all the reporting requirements in late 1970s and early 1980s, Hong Kong became the place to put your cash,” he said.

“Now, if I walked into a bank in Hong Kong with hundreds of thousands of dollars in cash, they will ask questions and they might not take it. They will report it,” he said.

“When I did this in the early 1980s, with such amounts of money, they would give me the red-carpet treatment. It was completely welcomed.”

The change occurred in the 1990s, Aitken said.

“Money laundering has become a very big issue now,” he said. “But I never thought it would become a crime, because people’s privacy was more important than the government collecting all this financial information.”

When I grew up in America, a snitch was the vilest form of creature. Now, America loves a snitch, if you are snitching for them

Hong Kong introduced the Anti-Money Laundering and Counter-Terrorist Financing Ordinance on April 1, 2012. The law was considered the first Hong Kong legislation to address money laundering as a main focus, including provisions encouraging the reporting of suspicious activities.

Aitken however, said a shift in values over the years also played an important role in the demise of his business.

“I was in jeopardy because of snitches. When I grew up in America, a snitch was the vilest form of creature.

“Because of my upbringing, I rely on faith, karma and fate more than wisdom,” Aitken said.

“I stumbled through life hoping that tomorrow is going to be a good day, instead of having a really good plan.”