How a Hong Kong man who stole a million dollars and went to jail went back to work in finance

Although criminologists agree employment keeps ex-convicts from reoffending, few can find full-time employment – but one small accounting firm goes out of its way to be different

After serving time behind bars for stealing HK$1 million from his company and losing his accounting credentials, Timothy Chan Hing-mo had little hope of ever working in the industry again.

Now the 40-year-old Hongkonger is back to crunching numbers thanks to a social enterprise accounting firm, believed to be the first of its kind in the city.

Prisoner rehabilitation is a job for Hong Kong’s community at large

Chan works at Navigator Consultancy, a financing and asset management company with a twist. Unlike the glitzy financial firms that operate out of Hong Kong’s central business district, four of its six-strong staff are former prisoners.

Although criminologists agree that employment is one of the best ways to keep ex-convicts free of crime, a 2015 survey found , only 20 per cent of former prisoners were employed full-time.

Navigator’s founder, Thomas Lau Kam-tai, a certified accountant himself, decided to open his own social enterprise in 2013 after noticing that many ex-inmates struggled to find jobs that suited them.

“Not everyone would like to work with ex-inmates. Once they know it, they will kind of freak out,” he said. “Eventually we have to do it by ourselves.”

Lau takes on inmates screened by the Correctional Services Department and trains them. People with a criminal record cannot pass the certified public accountants exam, but inmates who finish training at Navigator can still be independent accountants.

So far, 13 former employees have gone on to work at another professional services firm with which Navigator has an agreement.

“It’s not a good idea – it’s a disaster,” Lau said with a laugh when asked why he decided to pour extra effort into training ex-convicts in such a competitive industry. “I don’t think this is a clever way to [run an accounting business],” he said.

At first, Lau kept the social enterprise aspect of his business secret from clients, but it became public when he won a Spirit of Hong Kong award last year. Instead of turning clients off as he feared, he gained more of them.

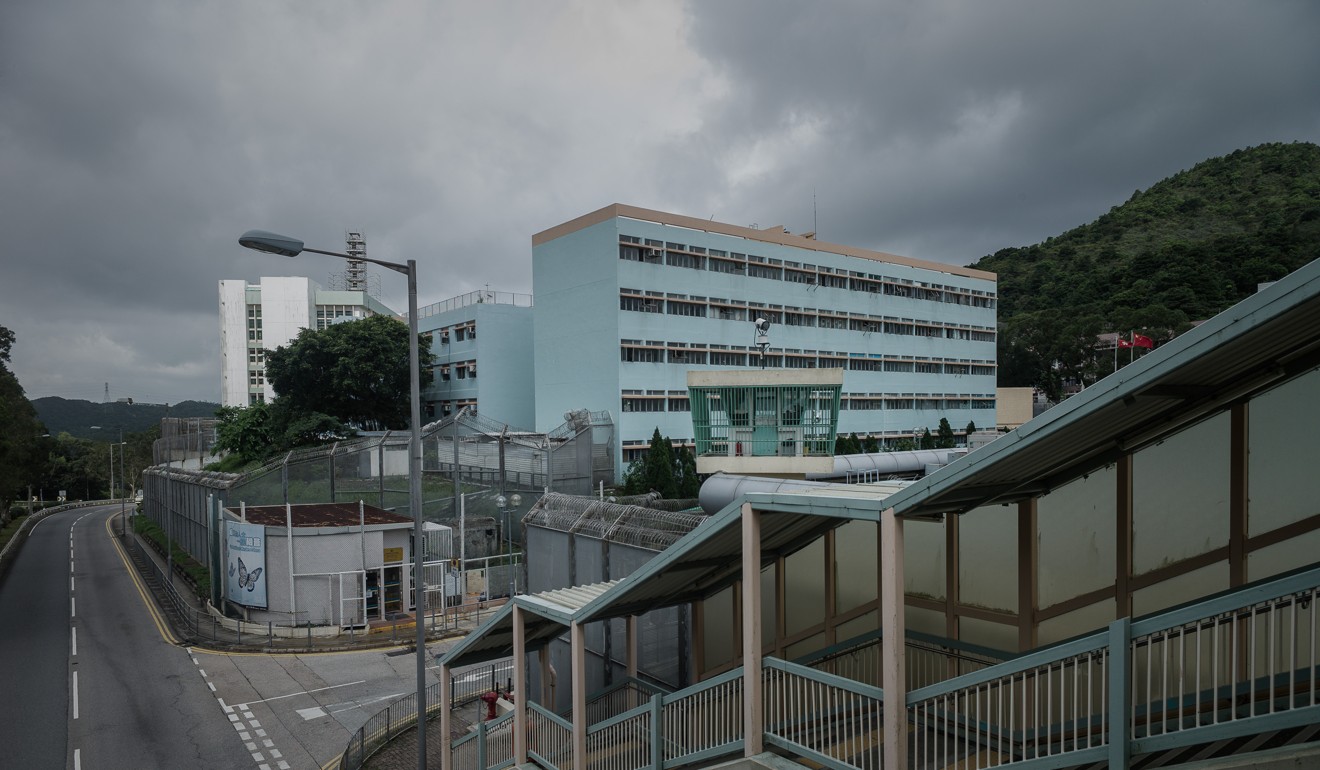

Chan, one of Lau’s first employees, spent five years in a mainland prison and another eight months in Hong Kong’s Pik Uk Correctional Institution after stealing over HK$1 million from the company where he worked as an accountant to fund his gambling addiction.

“To me, it was like a vacation when I came from the mainland [prison] to Hong Kong,” he said, adding that in mainland China he had cold baths and shared a tiny bed with another inmate.

He initially planned to resume his life of crime once he was released. But when he was given a surprisingly short sentence in Hong Kong, he saw it as a “miracle”, and started wanting to live a good life so that God would not punish him.

When he got out in 2012, employers would ask him why there was a six-year gap in his resume and would not want to take a risk when he told the truth.

Hong Kong’s prison system explained

His pastor finally referred him to Lau, who is also a Christian, and he scored a job at Navigator.

“Most of the jobs referred by the government involve labour work,” he said, adding that support was better for labourers. “When I went to offices, many of them gave the impression that they didn’t want to hire me anyway.”

Fellow Navigator employee Justin Ng, 30, was released from Pak Sha Wan Correctional Institution in Stanley in May after serving seven “horrible” months for theft.

Ng began working in accounting after graduating in 2008 and is currently studying to become a chartered financial accountant. He maintains his innocence, but if his appeal is not successful, he will not be able to get the certification.

He got a job at Navigator only a week after being released from jail through a pastor. But he said his friends who applied for jobs referred to them by prison officers never heard anything back.

“The government always says it is trying to help rehabilitated people in many ways. But when I’m in prison, did I get a lot of help from the government or the officers to cure my worries about when I come out of prison? I can say no, never. Nearly never,” he said.

“If you do not want the person to go to jail again, you need to tell them society will accept them and they do have a future,” he said.

“The problem now in Hong Kong is that rehabilitated people can’t see any future.”