Middlemen tell why dialogue to end Hong Kong's Occupy protests were doomed to failure

Middlemen blame officials' caution and students' reluctance for stalemate

Over-cautious senior officials and half-hearted student leaders dashed hopes of resolving the issues that triggered the Occupy Central mass sit-ins through a historic dialogue last October, according to two middlemen.

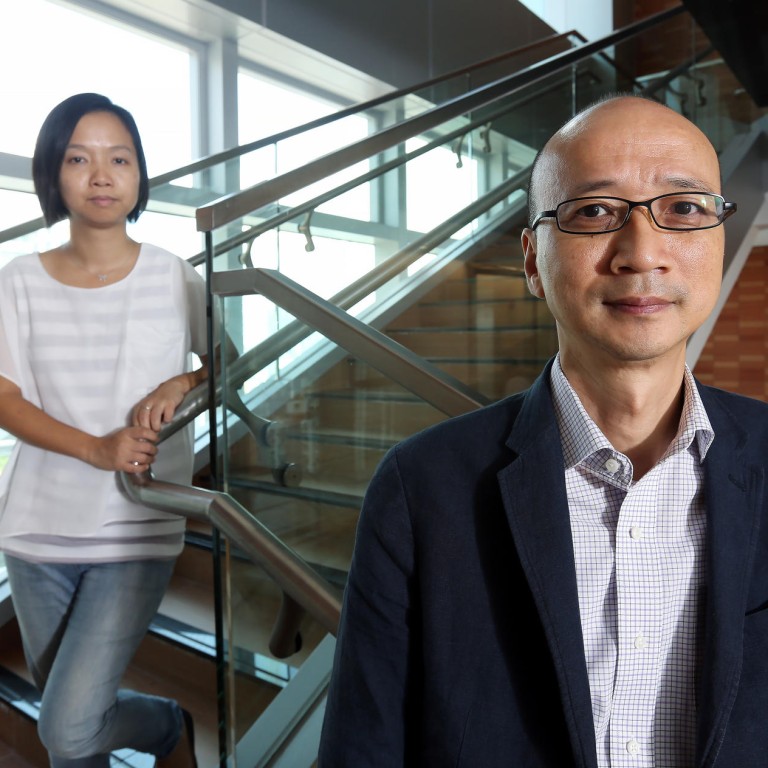

On the eve of the first anniversary of the protests, Professor Joseph Chan Cho-wai, a political scientist at the University of Hong Kong, and NGO worker Gloria Chang Wan-ki, president of the HKU students' union in 2000, broke their silence to the on their efforts to bring the concerned parties together for televised talks.

Their involvement started on October 15, when Chang received a phone call from then Federation of Students secretary general Alex Chow Yong-kang, who sought a meeting in Legislative Council complex that night to explore the possibility of talks with officials. Chan joined the meeting, and from that night to October 18, the duo conveyed messages between students and officials at separate meetings.

The students needed the middlemen to act before holding the formal talks. Chow said: "If we met officials behind closed doors, we were concerned that the protesters would think we had a secret deal."

So the next day, the pair met Chief Secretary Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor and HKU vice-chancellor Professor Peter Mathieson at the latter's residence in Pok Fu Lam.

In the exclusive interview with the , Chan said during their meetings with senior officials, he and Chang suggested that, in order to break the deadlock over the electoral reform, the SAR government should submit a supplementary report to the National People's Congress Standing Committee and set up a dialogue platform to discuss how to elect the chief executive by universal suffrage in 2017.

Watch: Intermediaries' efforts resulted in unprecedented televised talks during Occupy Hong Kong

But the government only partially adopted their suggestions, and the modified proposals put forward by Lam during the televised debate on October 21 failed to satisfy student leaders. They insisted Beijing retract its framework that capped the number of candidates for the 2017 election at three, each of whom must have majority support from a 1,200-member nominating committee.

During the talks, Lam told student leaders the government would submit a report to the State Council's Hong Kong and Macau Affairs Office - not the Standing Committee - to reflect public sentiment since the civil disobedience movement began. The government would also consider setting up a multi-party platform for dialogue on constitutional development "beyond 2017".

"During our discussions with officials before the formal talk, they were positive about our suggestion the platform should also cover the methods for electing the chief executive in 2017 and Legco in 2016, although they reiterated that such discussion must be conducted within the framework set down by the Standing Committee," Chan said.

"It appeared Carrie backtracked a bit as she said the platform would only discuss political reform beyond 2017. Carrie didn't fully deliver what we expected her to during the talks. So there was a natural disappointment on the side of students.

"But students could have used the dialogue, either that one or future ones, to press the government to clarify what they would like to do and get more from the administration."

Chang said students should have tried to dig up more details about the government's proposals during the debate "instead of just sticking to principles and moral high ground".

Chan said during their preparatory meetings with officials, he counter-proposed the government submit a report to the HKMAO after officials insisted it was "politically not feasible" to present it to the NPCSC.

"Secretary for Constitutional and Mainland Affairs Raymond Tam Chi-yuen suggested the government presenting a duplicate of the report to the standing committee and he would hand it in person to Basic Law Committee chairman Li Fei," Chan said.

But Tam and other senior officials present at the talks did not raise this point with students.

Officials had also suggested before the dialogue that the report would be written from the perspective of young people, as they were the major players in the protests. They even suggested a chapter could be written by the federation, Chan said.

But none of these points was raised to students by officials at the talks, Chan recalled, and Lam tended to act in a cautious manner during the debate, holding back her cards.

Students were also not keen, as they did not want to leave the public with the impression that they collaborated with the government, Chan explained.

He said he told officials students had agreed to give a "mixed response" to the proposals the government side would put forward. "This meant students would not reject the value of those proposals outright while maintaining they would not fully meet their expectations."

But student leaders lashed out at the government when they spoke to protesters in Admiralty that night. Chow's colleagues criticised officials for "playing tricks" and "fudging the issue".

"I was shocked by the negative tone expressed by various student leaders on the stage," Chan said. "I told students later, 'This is the last bridge with the government. Don't burn it."

He said the students’ critical attitude towards the government’s proposals put officials who were keen on dialogue, including Lam and Tam, in a difficult position.

The day after the debate, the two middlemen met the chief secretary at her residence on The Peak. "Lam asked us what had happened and if the students still wanted to continue the dialogue. We were unable to given an answer," Chan said.

There was no further dialogue after the October 21 meeting.

"I felt from the beginning the students had no clear goals," Chan said. "I didn't feel they knew what they wanted to achieve, other than to expose the constitutional problems of the Standing Committee's decision and criticise the government's handling of public consultation."

Chan stressed there was no agreement from the student side that they would retreat from the occupied streets even if the government fully delivered their proposals during the talk. "The officials were well aware of the students' position," he said.

In response to Chan's criticisms, Chow said students could not accept the government's proposal of setting up a platform to discuss reform matters only beyond 2017 as that was not their understanding from the middlemen before the dialogue. "It was a reason we felt further dialogue wouldn't help much," he said.

"Professor Chan did not share the same goals as us. There was lots of friction," Chow said, adding that Chan had sought to influence students' way of thinking.

Chan agreed he did not see himself as a "passive messenger": "We wanted to help students get as much concession as possible from the government, and when the government offered some things that we thought worth considering, we tried to persuade the students to accept them. Of course, at the end it was the students who called the shots."

Looking back, Chow said there were too many middlemen in the process, which was "a problem". Apart from the two acting between the students and the government, the Occupy trio also had their own middlemen who did not deal with the students. This, he said, might have caused confusion in the communication.