City Beat | Disappearance of booksellers puts ‘one country, two systems’ in the spotlight

The Lee Bo case gives both Beijing and Hong Kong much to reflect on – and raises questions about the value (or not) of holding a foreign passport

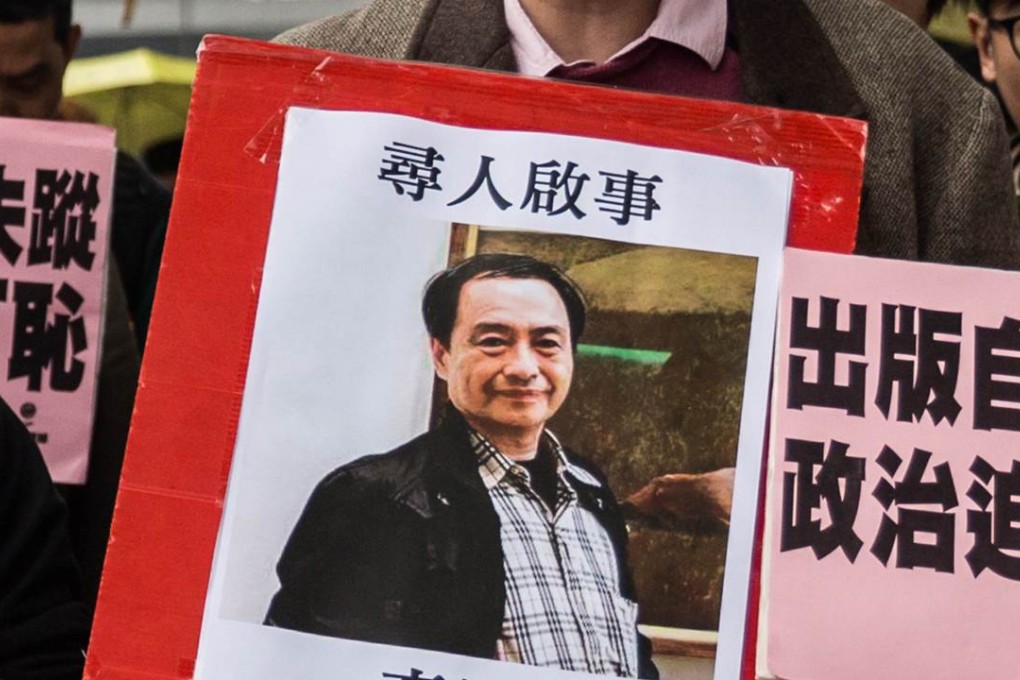

Without doubt, the biggest local news of the week must be the disappearance of Lee Bo and his four colleagues involved in the “banned book” business.

While many questions remain unanswered on what could have happened to them, especially Lee – who, unlike the others, went missing in Hong Kong – there is no doubt that if mainland law enforcement people have ever carried out duties in the city, it is a serious violation of “one country, two systems” and should not be allowed, as Chief Executive Leung Chun-ying stressed.

The case turned even more mysterious when Lee Bo later told his wife via fax that he had gone to the mainland using “my own way”. A commentary in the mainland’s Global Times therefore concluded that this quashed the rumours that Lee had been “abducted” by mainland “agencies”. But the next day, it published another commentary saying that “powerful agencies” all over the world have their ways to get around laws to get someone for investigation. Thus it’s also lawful for mainland agencies to invite these booksellers for investigation since the books they published had created a “disturbance” on the mainland.

No wonder many people in Hong Kong took it as “evidence” that Lee was indeed “taken away” by mainland agencies, though details of “how” were not known – not even, it seems, to the Hong Kong police. On the other hand, given its provocative track record, how much this paper under People’s Daily represents the real thinking of Beijing is another question. One local Chinese paper quoted sources saying that certain mainland authorities “were not happy” about Global Times’ two commentaries because they only added fuel to Hongkongers’ worries and anguish. This might indicate the different approaches among various mainland authorities in handling sensitive matters in Hong Kong.

After Foreign Minister Wang Yi met his British counterpart, Philip Hammond, last week he told reporters that Lee, a British passport holder, was “first and foremost a Chinese citizen” and dismissed “groundless accusations” against Chinese authorities. The British side “expressed deep concerns”, adding that if Lee’s disappearance was indeed a result of mainland agencies crossing the border conducting actions, that surely violated “one country, two systems”.

Two days later, the European Union issued a statement, urging authorities in Hong Kong, China, and Thailand to investigate and clarify the disappearance of the five, as two of them are EU residents – apart from Lee, one is Swedish.