Lee Po, the main actor in the mystery of the missing booksellers, and the five questions to be solved

Today, exactly a month since Lee Po vanished, five key questions hang over the case of the missing Hong Kong booksellers

1. How did Lee Po get to the mainland?

One of the most curious aspects of the case of Lee Po, formerly known as Lee Bo, is how he travelled to the mainland from Hong Kong. Lee, a co-owner of publishing house Mighty Current, which runs the Causeway Bay bookstore, was last seen on December 30 at Mighty Current’s Chai Wan warehouse at about 6pm.

Lee went missing about two months after four of his business associates, Gui Minhai, Lui Por, Cheung Ji-ping and Lam Wing-kei, disappeared separately in October – Gui while on holiday in Thailand in mid-October, and Cheung, Lui and Lam later that month in Shenzhen.

Late in the evening of December 30, Lee called his wife from a Shenzhen phone number and told her in Putonghua, not Cantonese, that he was assisting with an investigation. The next day his wife found his home permit in their house, prompting her to file a missing persons report. It then emerged from police that there was no record of Lee leaving the city.

One of the main reasons Lee’s disappearance has become a major concern is speculation that Lee was abducted by mainland law enforcement agents in Hong Kong and taken to the mainland against his will. If this occurred it would be a significant breach of the principle of “one country, two systems”.

The possibility remains that Lee may have decided to travel to the mainland of his own volition. He told his wife in a January 4 letter he had “returned to the mainland my own way”. In a January 17 letter to his wife, Lee said he “voluntarily went to the mainland”.

This scenario has thrown the efficacy of the border control points into question after former secretary for security Regina Ip Lau Suk-yee said earlier this month that Hong Kong permanent residents could enter and exit the city freely without going through specific control points as this was not an offence.

Ip, now the chairwoman of New People’s Party, cited fishermen and rich people sailing away during weekends as examples of this.

However, the Security Bureau was quick to hose down the suggestion of an immigration grey area, saying passengers on vessels were still required to give details to the ship’s captain, who was then required to liaise with the Immigration Department.

The lack of evidence of immigration clearance remains one of the most baffling aspects of Lee’s case, fuelling anxiety and mainland antipathy in equal measure the longer the mystery drags on.

2. What is the role of the Hong Kong government?

In the initial aftermath of Lee’s disappearance, Chief Executive Leung Chun-ying spoke out strongly in response to speculation that Lee had been abducted by mainland authorities, saying it was neither acceptable nor constitutional for mainland agencies to take law enforcement action in Hong Kong.

But the hands of the government and the police force appear to be tied when raising the case with their counterparts on the mainland, and the ability to investigate or probe seems limited.

Under a reciprocal mechanism, law enforcement agencies on the mainland must notify the city’s police within 14 days if any Hong Kong resident is detained across the border.

The Guangdong Provincial Public Security Department only replied to an inquiry by the city’s police on January 18 – more than two weeks since the police first followed the case after a missing person report was filed by Lee’s wife – and all it did was to confirm Lee was “on the mainland”.

A surprise meeting last weekend between Lee’s wife and her husband in a secret location on the mainland also highlighted the passive role of the city’s administration and sparked criticism that the Hong Kong government was being sidelined. Police said the meeting was not arranged by them and they were merely informed by Lee’s wife, who remained tight-lipped over the meeting venue, hours after the reunion took place. The police have subsequently renewed their request to the Guangdong security officials for a meeting with Lee.

Until now, neither the chief executive nor Police Commissioner Stephen Lo Wai-chung has revealed whether they have appealed to Beijing’s liaison office in Hong Kong or to a higher level, the State Council’s Hong Kong and Macau Affairs Office, over the case.

3. What is the investigation all about?

The subject and reason for the investigation which drew Lee to the mainland remains an enigma. In the early days after his disappearance, a handwritten letter, reportedly faxed from Lee and published by Taiwan’s Central News Agency, said he was “working with the concerned parties in an investigation which may take a while”. He also told his wife in a letter on January 9 that he had returned to the mainland “in order to understand some personal issues, it is not related to anyone else”.

But a January 17 letter from Lee, alluded to his colleague Gui Minhai. In a surprising twist, Gui had appeared on state TV on January 17, claiming he had surrendered to the mainland authorities after fleeing from a suspended two-year jail term since causing a fatal drunk-driving accident in 2004. In a letter that day to his wife, Lee said he had been implicated as a result of the acts of Gui, who was a “morally unacceptable person” and “involved in other crimes”.

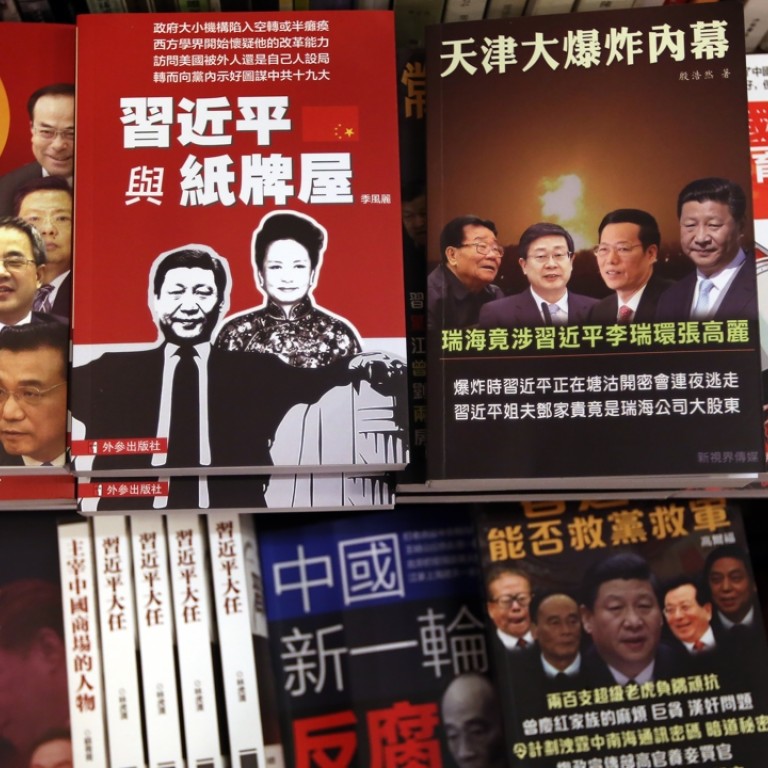

With the rumour that Mighty Current had been preparing the launch of a book about President Xi Jinping’s love affairs at the time of the disappearance, it has also been suggested Lee’s case was the result of an alleged “Guangdong Action Plan”. This is said to be the order of Beijing dated last year to grant authorisation for cross-border operations to stamp out the publication of materials that are banned on the mainland.

There was also a sordid detour in the saga when Beijing-friendly lawmaker Ng Leung-sing quoted a text message in the legislature meeting, claiming Lee and his associates had been caught by mainland officers while having fun with prostitutes. The claim was condemned by Lee’s wife and also later denied vehemently by Lee in two of his letters.

4. What are the implications for Hong Kong-mainland relations?

The unprecedented controversy, which has made headlines around the world, has placed the integrity of the principles of the Basic Law and “one country, two systems” under scrutiny, if not in serious doubt. The perceived delay by mainland authorities in responding to requests for information from the Hong Kong police has been interpreted as a snub to the government and chief executive.

As internet users enthusiastically discuss the need to renew their British National (Overseas) passports as an “escape door” in the wake of the disappearance of the booksellers, the case is also set to pave further obstacles on the government’s extra funding request for the express railway connecting Guangzhou and Hong Kong, which involves the creation of a co-location immigration checkpoint in the West Kowloon terminus.

The legal concerns surrounding the checkpoint have remained unresolved for years as lawyers and some lawmakers have warned it could potentially allow mainland security officers to search and detain Hongkongers who have not committed any local offence at the joint checkpoint. The case of Lee Po has confirmed such fears – now being aired again by some pan-democrats who already have reservations on approving the extra funding.

Meanwhile, the alleged abduction has also triggered a chilling effect on the book publishing industry, with publishers – including chief editor of Open Magazine, Jin Zhong – saying they might take a step back and “strike a balance” after the incident, seemingly a well-planned operation by Beijing.

Politically, the unresolved case could add a layer of uncertainty to the performance of the pro-establishment camp in the Legislative Council elections in September. The camp has been ambivalent over the drama.

Professor Kerry Brown, director of the Lau China Institute at King’s College in London, warned that China could face condemnation by the international community should it turn out that it indeed did nab the five.

5. Is there a way to bring resolution to the situation?

Veteran China watcher Johnny Lau Yui-siu concedes that the ball is firmly in mainland China’s court, but he says the city’s administration has not done enough to demand the whereabouts of the missing Hongkongers.

Leung Chun-ying should and still could make good use of the existing communication mechanism between the city’s administration and the coordination team under the State Council’s Hong Kong and Macau Affairs Office, he says, to press the case to Beijing directly.

Lau says the coordination team is headed by Zhang Dejiang, chairman of the national legislature who is the top official in charge of Hong Kong affairs, and has dealt with various important issues such as political reform that was eventually rejected by the city’s lawmakers last year.

“Until now, Secretary for Security Lai Tung-kwok was still saying he was not sure whether the notification system [between mainland authorities and Hong Kong police] would apply to the case of Lee,” says Lau. “The government should not handle the matter in such a passive way but instead must adopt the highest level of means available on their table.”