Why controversy marches to the tune of China’s national anthem

A proposed new law on the mainland to protect the song from abuse has sparked debate on its application in Hong Kong

Controversy is nothing new in the zigzag course of the anthem’s history. Launched as a film song in 1935, the March of the Volunteers became a No 1 hit with its stirring rhythm and lyrics rallying a China at war with Japan.

But decades later, during the Cultural Revolution, the anthem fell from grace and was seldom played. On the rare occasion that it was sung, the words were changed as lyricist Tian Han was seen as a traitor.

The song’s fortunes turned again as it became a staple of Hong Kong’s national education initiative in 2004, galvanising an increasingly mixed reception in society. On paper, the score takes up a mere 37 bars, but the debates it has triggered continue unabated.

What are the anthem’s origins?

It was a song in the movie Children of Turbulent Times, shot and premiered in Shanghai in 1935. The film was about the political awakening of young people who enlisted as volunteers to fight Japanese invaders. March of the Volunteers was recorded and released as part of an album that sold like hot cakes. With the outbreak of full-scale war with Japan on July 7, 1937, the song, with its marching tune and stirring lyrics, became the most famous battle song around the country.

Watch: Venezuelan military band plays out-of-tune Chinese anthem

When did it become the national anthem?

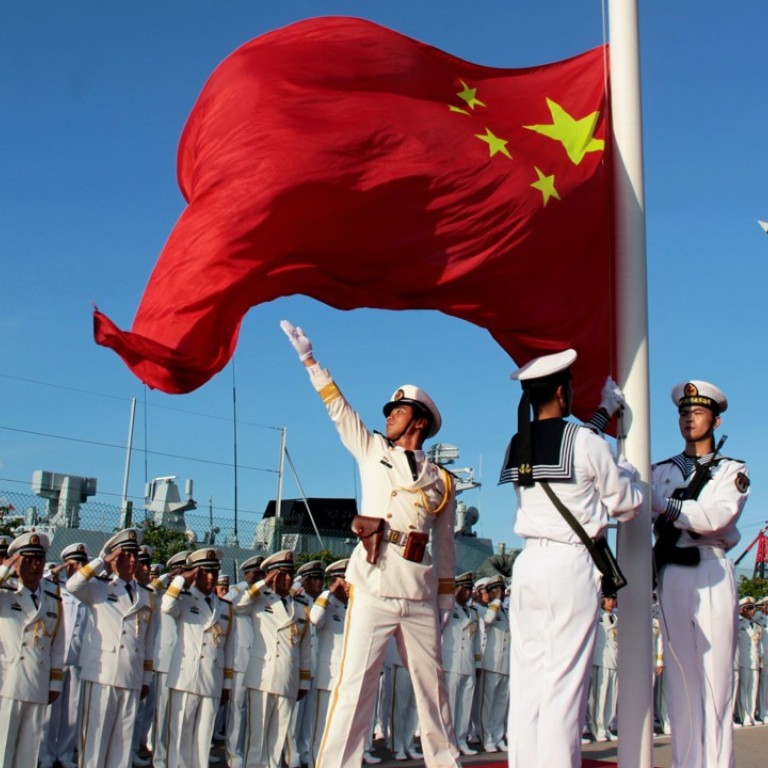

Along with the five-star flag, the March of the Volunteers received its official status at the first session of the Chinese People‘s Political Consultative Conference in September 1949. Communist China’s founding father Mao Zedong gave his approval by singing it.

The song was replaced by The East is Red as the unofficial anthem during the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976) when its lyricist, Tian Han, was branded a traitor and died in prison in 1968. The song was reinstated in 1982 as the national anthem. This was written into the constitution as part of Article 136 in 2004.

How was the anthem received in Hong Kong?

The general reception was good as the city was also a victim of Japanese occupation between 1941 and 1945, and the older generation was brought up singing the anthem. It did not play a prominent role in the 1967 riots, as the battle song then was The East is Red. The reception for the anthem reached a climax in 1989 when up to a million people took to the street chanting the lyrics “millions of but one heart, braving the enemy fire” in support of the pro-democracy movement in Beijing.

When and how did attitudes towards the anthem change?

One such incident involved local soccer fans booing during the anthem ahead of a 2015 World Cup qualifier, an act that led to the Hong Kong Football Association being fined by Fifa, the international governing body for soccer. The situation further deteriorated at last April’s match between Guangzhou’s Evergrande and Hong Kong’s Eastern when mainland fans hoisted a large banner that read “annihilate British dogs and extinguish the poison of Hong Kong independence”.

Will the proposed law on the national anthem bring an end to the controversy?

Last month, the National People’s Congress standing committee discussed a draft law on the national anthem, which includes a clause punishing anyone maliciously changing the lyrics or the song with up to 15 days in detention.

Legal experts in Beijing and Hong Kong differed in their views on the proposed bill’s application in Hong Kong. Peking University law professor and Basic Law Committee member Rao Geping said he thought the bill, once adopted, would apply to Hong Kong. But local legal experts, including Basic Law Committee adviser Albert Chen Hung-yee, said a national law would have to go through local legislation before taking effect as a part of Annex III of the Basic Law.

Addressing concerns on the issue, Elsie Leung Oi-sie, chairwoman of the Basic Law Committee, said: “Don’t be scared. If there are rules we can’t accept, I don’t believe the Legislative Council will pass them.”

The controversy over the anthem seems, like its ending line, to “march on, march on, march on”.