How Hong Kong’s grand ministerial plan fell short

Tung Chee-hwa overhauled the governance system in 2002 with the aim of recruiting political appointees more in tune with the public’s wishes. It didn’t quite happen, and there is no consensus on how to improve things

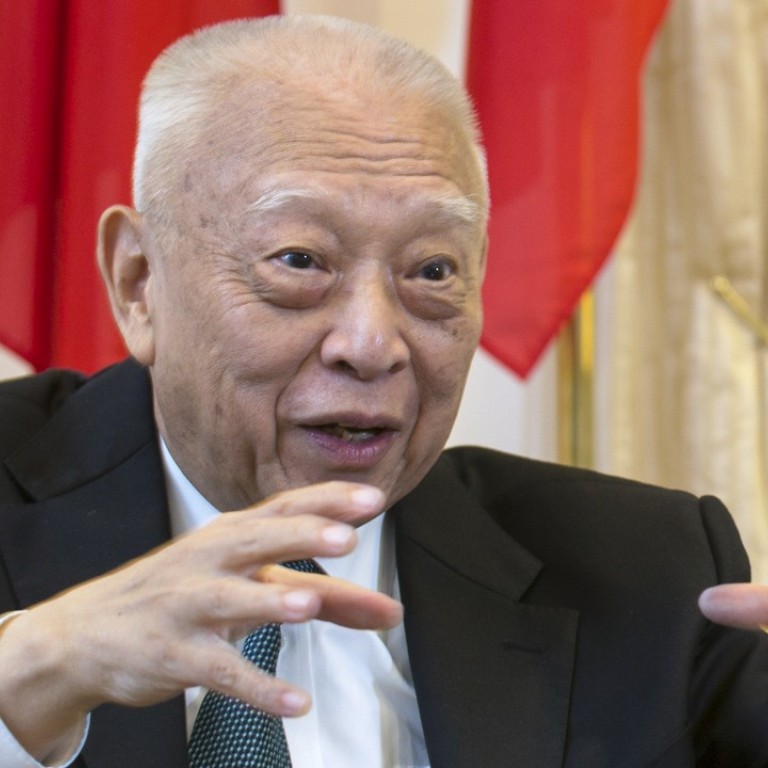

The first leader to take on the job of running Hong Kong after the city’s return to Chinese sovereignty in 1997 had a significant admission to make on the 20th anniversary of the handover.

Former chief executive Tung Chee-hwa told the Post that the ministerial system he introduced 15 years ago to run a more politically accountable government did not produce the results he expected – though he stopped short of calling it a failure.

Tung, now an elder statesman as a vice-chairman of China’s top political advisory body, touched upon an issue that had been causing a fair amount of concern in the lead-up to the handover and continues to be the subject of strong debate, given Hong Kong’s changing social and political landscape and what is seen as a more hands-on approach by Beijing regarding the city’s affairs.

Before 1997, colonial government practice was to fill top government positions with career civil servants. They were mainly accountable to the chief secretary or financial secretary – the city’s No 2 and No 3 officials – who would in turn report to the only political appointee – the British governor picked and sent over by London.

This system was inherited and continued after the handover by Tung’s administration. At a time of transitional uncertainty, apprehension and even insecurity, the arrangement offered some stability and reassurance.

But in 2002, armed with the confidence of running the city for a full five-year term, Tung undertook a major restructuring of the governance system. He introduced the Principal Officials Accountability System, going for a ministerial set-up under which political appointees from the private sector would help him run the government instead of top bureaucrats.

The reasoning was that it would give civil society more of a voice in how the government should serve it – that approach began earlier with the city’s first popular elections to the Legislative Council in 1991 – but there had been no corresponding reform in the executive system.

“The ministerial system that was introduced in 2002, it was necessary, because if they didn’t do anything [Hong Kong] would have exploded,” University of Hong Kong academic John Burns said.

It was a significant change, and was seen as diluting the clout that the chief secretary at the time, Anson Chan Fang On-sang, had inherited from the British. She quit her post the year before the new system was implemented.

In theory, the move away from appointments based on civil service seniority should have made ministers more accountable, and therefore more sensitive to the needs of the person on the street.

Tung stepped down before his term finished in 2005, citing health reasons while under heavy public criticism of his leadership.

For reasons that can be argued over to this day, it did not bring the accountability that was promised or produce the political talent it was designed to.

“Maybe it was a misnomer. It’s a political appointment system more than an accountability system,” according to New People’s Party legislator Regina Ip Lau Suk-yee, once a minister under Tung.

Ironically, Ip herself was an early casualty of the accountability system. She stepped down as security secretary in 2003 in the face of mass protests against the government’s push for national security legislation.

The city is obliged, under its mini-constitution, the Basic Law, to prevent acts of treason, sedition, and succession against the state, but Tung’s administration was unprepared for the backlash among a public that feared a rolling back of the freedoms Hong Kong enjoyed under the “one country, two systems” formula.

If we keep referring to it as an accountability system people will think that ‘heads should roll’ and very few heads have rolled

Ip, a staunch proponent of national security legislation, turned out to be one of only three ministers who ended up resigning since the accountability system was introduced. Other top officials, in the years that followed, were seen to resist public calls to step down over blunders and scandals for which they were held responsible.

“If we keep referring to it as an accountability system people will think that ‘heads should roll’ and very few heads have rolled,” Ip said. “So it’s a disappointment from that perspective.”

But she cautioned against expecting ministers to resign for “any issue of public concern”.

“If we did that, no one would want to join government,” she said.

The limited pool of available political talent was also a problem Lam faced, though this was something that was supposed to have been solved by Tsang’s Political Appointments System in 2008.

Former opposition lawmaker and Civic Party leader Alan Leong Kah-kit said Lam’s difficulties reflected the failure of Tsang’s system to create a pool to dip into in the first place.

Ip suggested Tsang “went overboard” with his system upgrade. She said that while the ministerial and deputy ministerial levels were necessary to handle the policy workload, the political assistants – forming the third tier – were overpaid for doing nothing more than “liaising” work.

“What have they been doing? Very few of them have shown that they have sunk their teeth into complex policy issues,” she said.

Burns said the ministerial system had brought in “political accountability” as opposed to “bureaucratic accountability”. Making a top bureaucrat resign would only be possible if he or she violated civil service regulations.

One of the most criticised ministers in the Leung administration was Secretary for Education Eddie Ng Hak-kim, who resisted calls for his resignation over more than one policy crisis.

In 2012 he was forced to shelve plans to add national education in the school curriculum because of a widespread public backlash over “brainwashing” concerns. According to Burns, this was an example of accountability, as the minister would not have had to back down before the system was introduced in 2002.

In his interview with the Post this month, Tung identified low pay as one of the weaknesses of the system, suggesting salary levels were not competitive enough to lure talent from the private sector.

“The pay is not high enough. You look at Singapore, what the pay is,” he said.

“If I’m 50 years old, I want to contribute to Hong Kong, I come, I take a salary cut and I work for five years, and the newspapers beat me to death. And then he loses the job and he can’t do it.”

But problems went deeper than just pay, according to Leong.

The so-called accountability system has one fatal deficiency: we do not have a system under which a political party is voted in to office after a general election

“The so-called accountability system has one fatal deficiency: we do not have a system under which a political party is voted in to office after a general election.”

Without a party-led government, officials were not really required to step down as a result of major errors in policy that a political party in government would otherwise be committed to, Leong added.

Former Legco president Jasper Tsang Yok-sing saw the accountability system as an improvement on the pre-2002 set-up, but agreed that it wasn’t good enough.

“Everything has become so political now. We need politicians; we need people with political skills and political insight,” he said.

While most agree that the current system of governance is not ideal, there is no consensus on what should be done to improve it.

So far, the new chief executive, while regularly touting a new style of governance, has gone back to the civil service pool to promote veteran bureaucrats to ministerial positions or hold on to key officials already in place. There has been no indication of any change as far as greater accountability is concerned.

“If you asked me, if we would go back to a civil service type of government after [Leung Chun-ying’s] United Front government, I would have thought you were crazy,” Burns said.

Short of full democracy, which opposition pan-democrats are pushing for, a party-led government is a possible first step towards improving governance. But will Beijing allow it?

Jasper Tsang said it was a public misconception that the Basic Law prohibited the chief executive from being a member of a political party – the prohibition was in the Chief Executive Election Ordinance instead.

“That can change and will have to change,” he said. “The social conflicts that have developed as our economy grows require a government with very clear political conviction to resolve [those conflicts].”

Tsang suggested “training programmes” for aspiring administrative officers within the civil service to create more political talent for the government. Tung had suggested something similar.

But Tsang admitted that any proposal to improve governance would only partly solve such issues because Hong Kong’s political structure was unique, with the chief executive beholden to the central government in Beijing.

Leong identified the same problem, saying that even with an improved system in place, ministers would not be truly accountable to the public because they would still answer to a boss who would be accountable to the central government. There was no option to vote them out.

Give the status quo, accountability is set to be a controversial subject that is bound to crop up every time members of Lam’s new administration are seen to fail in policy areas they are responsible for.