Is Chinese national education set to make a comeback in Hong Kong? It’s not if, but how, experts say

Some form of national education is important for the city, educators say, with debate focusing on how it should be done and the materials used

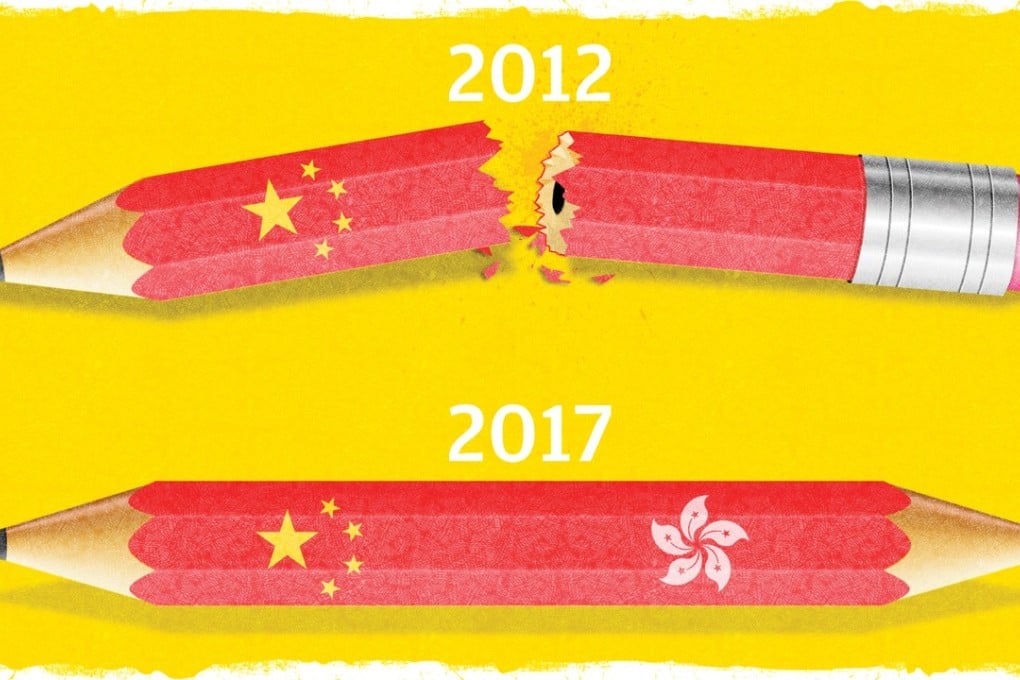

Five years after the previous Hong Kong administration was forced to shelve plans for a national education curriculum in local schools following 10 days of protests against the idea, the contentious issue is once again back in the spotlight.

The concept, aimed at instilling patriotism and strengthening Chinese identity among local youngsters, became a major stumbling block for former Hong Kong leader Leung Chun-ying, with critics accusing him of trying to “brainwash” children with Communist Party propaganda amid fears in Hong Kong of the mainland’s growing influence in the city.

Previous governments have for the most part attempted to keep the idea under the rug, anticipating a fierce reaction from Hong Kong localists and pro-democracy activists.

But new leader Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor, who took over from Leung as chief executive on July 1, has made the topic a priority from the get-go despite the anticipated pushback.

In the last couple of months, her administration has been outspoken about instilling patriotism in pupils, which has stoked fears among parents, educators and students that plans for a compulsory course could be revived.

And the issue was back in the spotlight again on Tuesday when the government appointed Christine Choi Yuk-lin as undersecretary of the Education Bureau. Her former connections with the pro-Beijing Federation of Education Workers, a teachers’ association, sparked fears she could push for a national education curriculum biased towards the Communist Party line. Those fears led to a petition being filed against Choi taking the role, which gathered more than 17,000 signatures.