Read the Hong Kong Court of Appeal’s ruling on Joshua Wong, Nathan Law and Alex Chow, jailed for 2014 protest

A translation of key parts of the 64-page document, which was only made available in Chinese

The jailing of three Hong Kong political activists on Thursday has drawn fire from the city’s pro-democracy camp, but been lauded in pro-establishment circles. It has also provoked questions on judicial independence, which were challenged by legal professional bodies and the Secretary for Justice Rimsky Yuen Kwok-keung.

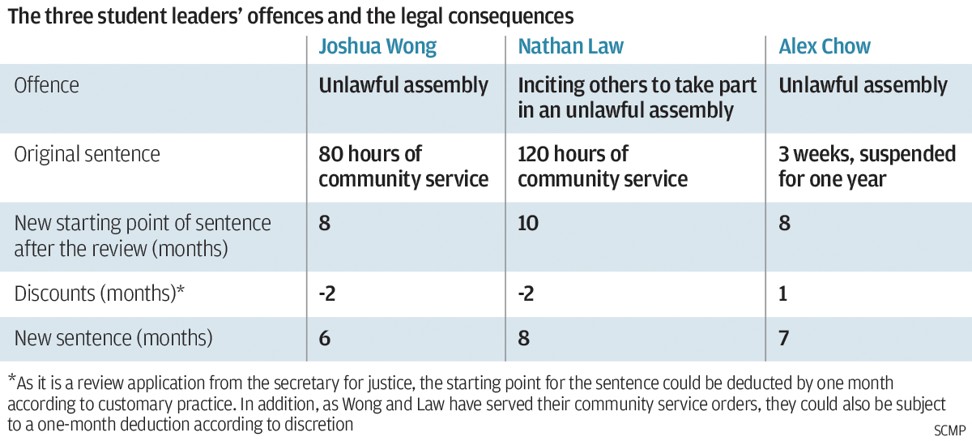

Joshua Wong Chi-fung, Nathan Law Kwun-chung and Alex Chow Yong-kang were jailed for six to eight months for their parts in clashes at the government headquarters in Admiralty, soon before the pro-democracy Occupy protests of 2014. Wong and Chow were found guilty of unlawful assembly, and Law of inciting others to take part in an unlawful assembly. Law and Wong at first got community service, while Chow was given a suspended jail term. On Thursday the Court of Appeal sent them to prison, finding the earlier punishments insufficient.

Below, translated into English, are highlights of the court’s 64-page ruling, which was only made available in Chinese.

What happened?

On September 26, 2014, respondents from different groups attended a rally in the area in front of the government headquarters, next to Tim Mei Avenue. They were given a notice of no objection from police before the rally, and the notice was valid until 10 o’clock that night.

On the same day, the two gates of the fence of the area in front of the Central Government Offices were closed for security reasons. When the incident happened, security guards were on duty in front of and behind the gates. There were also [metal] barriers in front of the gates.

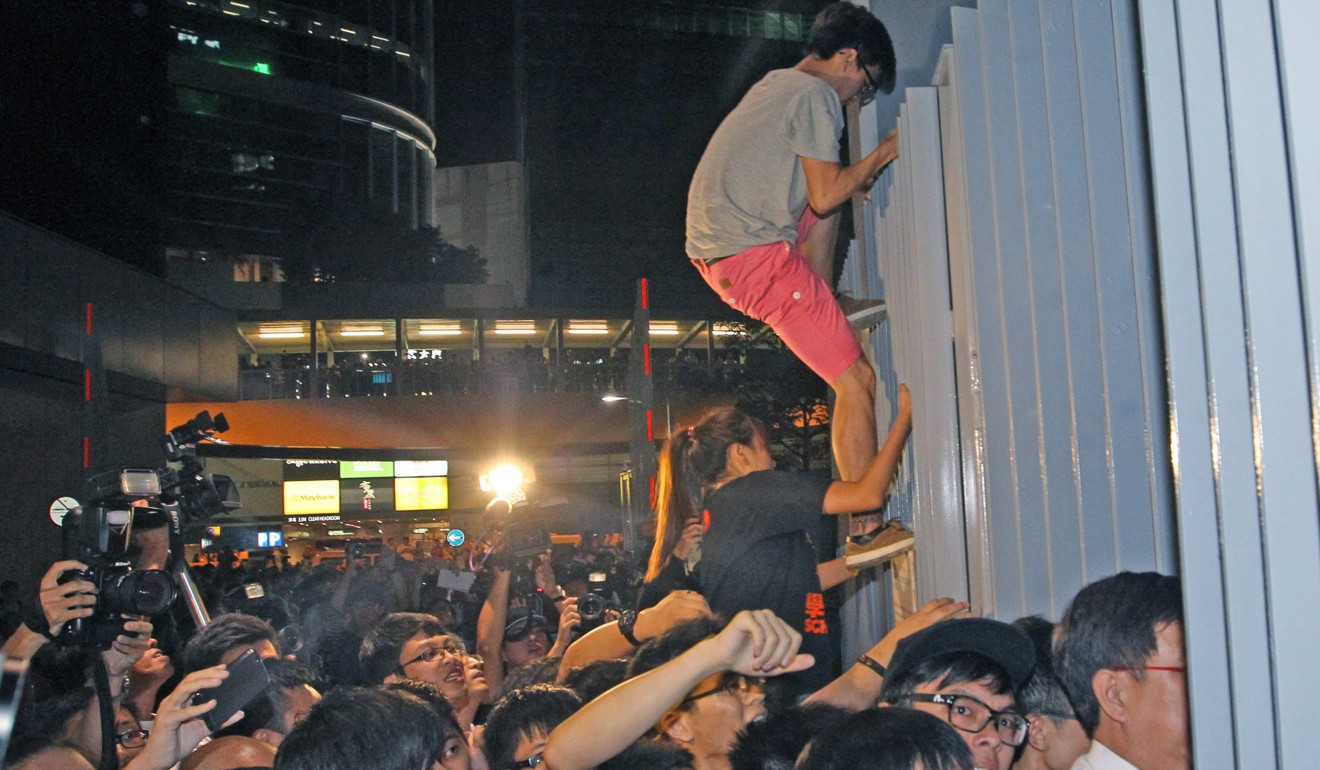

The rally finished at about 10.20pm. When the participants began to leave, Wong ran onto the podium and used the radio system to call on them to stay and get into the area in front of the Central Government Office. Then Wong passed his role as the host of the rally to Law, while he himself ran to the area in front of the Central Government Offices.

Law took over the position of Wong and stood on the podium while calling on the people to enter the area. Hundreds of rally participants climbed over the fence and forced open the closed gates, against the efforts of security guards and police officers.

Finally, dozens of rally participants managed to enter the area. Some of them pushed down the barriers placed under the flagpoles there, where subsequently the people, including Chow, joined hands and shouted slogans. It lasted about 12 minutes from when the first respondents called on the people to enter the area to when they surrounded the flagpoles.

During the incident, a total of 10 security guards at the Central Government Offices got injured while they were preventing the rally participants from entering the area. Most of them suffered from slight injuries, such as tenderness, bruises and swelling. Security officer Chan Kei-lun was more seriously injured. He suffered from bruises and swelling on his left foot toe and a slight fracture near his first phalanx. He took sick leave for a total of 39 days.

Trial magistrate June Cheung Tin-ngan’s reasoning for her sentence in August 2016

● The respondents are all leaders of student democracy movements in Hong Kong, who come from both grass-roots and well-off families. They have had good academic performance, and do not have any criminal records. They are enthusiastic about social issues, and committed to politics. Their families understood and supported what they were doing.

● The trial magistrate thought the case was different from ordinary criminal cases, and that the purpose behind their committing the offence should be taken into account apart from the seriousness of the case. She was satisfied that the respondents took their actions because of their political beliefs and in light of the social conditions, and not for their own interests, nor for their attempts to hurt others. She pointed out that young people were pure and innocent, did not take into account actual interests, or might be impulsive. Therefore, when sentencing, the magistrate took a more tolerant and understanding attitude to the respondents’ motives.

● The trial magistrate also said the case occurred earlier than the more radical political events such as the Occupy protests. She also considered that if the subsequent political environment was taken into account, deterrent penalties would become unfair to the respondents. On top of that, she considered their behaviour in the case much more moderate than in subsequent political events.

● The trial magistrate was of the opinion that the respondents’ actions were not very violent. She said they had merely entered “Civic Square”, which they believed was a meaningful and representative place and where they formed a circle and shouted slogans.

● Although the respondents were convicted after trial, they showed cooperation during the arrest, investigation and trial. They expressed respect for the court: they did not deny their participation in the incident or the acts they had done. They only questioned whether their acts had constituted offences. They also told the probation officer that they were willing to take legal consequences and to accept the penalties in the form of community service orders.

What is a community service order and when is it applicable?

●A community service order is a common form of sentence passed by lower courts upon conviction for unlawful assembly.

● The court may issue an order to a person aged 14 or above who is found guilty of an offence punishable by imprisonment, to carry out unpaid work in accordance with the provisions of this ordinance during the validity period of the order. The number of hours of work is specified in the order, but can not exceed 240 hours.

● A community service order has the elements of penalty and rehabilitation. A community service order is also a remedy for the perpetrator to contribute to society through unpaid work, so that members of the public can benefit from them for damage they have caused.

● Some believe that a person receiving a community service order should meet the following conditions: it is the first offence by him or her; the crime was minor; he or she comes from a family with a stable background; he or she has a good occupational record; and he or she shows sincere remorse. At last, he or she has a low possibility of committing the crime again.

Errors made in the initial sentencing, according to the Court of Appeal

● The trial magistrate did not consider that the sentence should have a deterrent element, while giving disproportionate weight to factors such as personal circumstances and the respondents’ motives.

● The trial magistrate did not think the case involved serious acts of violence. However, she ignored the fact that the rally was a large-scale unlawful assembly, where the risk of violent conflicts was high.

● Given the prevailing and objective circumstance, the respondents should have reasonably expected the people involved in the incident would clash with security guards and police officers, and that injuries would then be inevitable. However, the trial magistrate completely ignored this point.

● The trial magistrate overlooked that, before the incident happened that night, the Hong Kong Federation of Students and Scholarism had finished the rally on the road next to the government offices, and the area in front of the government offices was closed. They had no absolute right to enter the area to hold the rally, but they insisted on illegally entering it by force. They also encouraged or incited others to illegally enter it by force. They thought they were correct in doing so and their acts were in breach of the law.

● The trial magistrate gave disproportionate weight to remorse as a factor in sentencing. In fact, the respondents ... still insisted that they were correct in entering the area by force. It was because they always thought they were simply exercising their freedoms of speech and of assembly. The first respondent even said in his community service order report that he had no remorse at all for what he did. The third respondent also made a similar statement in his community service order report.

Even if the respondents did not deny the acts they had done, and expressed respect for the court and were willing to bear the legal consequences of the conviction after the trial, their “remorse” was superficial. The proportion of weighting given by the court to the factors should not be too high.

In summary, the magistrate made a principle error by granting a community service order for the respondents, which was clearly too light. Therefore the Court of Appeal needs to intervene.

New sentencing guidelines for cases involving violent unlawful assemblies

● In accordance with the general principle for sentencing, the court shall take a full account of the actual situations about the case and the seriousness of the circumstances of the crime, and then give a proportion of weighting to each applicable sentencing element, before the perpetrators are given a sentence commensurate with the crime. The same principle applies to cases involving violent unlawful assemblies.

●Under the premise of maintaining public order, and in light of the seriousness of the unlawful assembly, the court, while sentencing, needs to consider the deterrent element. The proportion of the element shall depend on the circumstances of the case.

● If the case is relatively minor, for example, if an unlawful assembly is unpremeditated and small in scale, involves slight violence, and did not cause any personal injury or property damage, then the court shall update sentencing elements and increase the proportion of weighting to the individual circumstances of the perpetrators and the motives or reasons for committing the crime, while the deterrent element would proportionately be reduced in sentencing.

● If the case is serious, for example, it is a large unlawful assembly involving violence or serious violence, the court shall give a large proportion of weighting in sentencing to the two elements of punishment and deterrence, while the proportion of weighting for factors such as the personal circumstances, the perpetrators’ motives or reasons of committing the crime would be given a small proportion of weighting or would not be given any weighting under extreme circumstances.

Translated by Nelson Cheng