Six things to know about Hong Kong’s controversial ‘co-location’ joint checkpoint scheme

Top legislative body in China approves legal foundation for the plan to be implemented

The standing committee’s endorsement was required because under the checkpoint “co-location” proposal, mainland Chinese officers will be unprecedentedly given almost full jurisdiction over part of the West Kowloon terminal leased to them.

Since the Hong Kong government unveiled the proposal in July, its legal basis has remained unclear, and has been hotly debated among officials, legal experts and legislators.

Officials and pro-Beijing figures also said the endorsement offered an “unchallengeable” legal foundation for the checkpoint plan to be implemented.

1. What is the “co-location” arrangement all about?

The 26km Hong Kong section of the Guangzhou-Shenzhen-Hong Kong Express Rail Link cost HK$84 billion to build. After it is opened in September next year, it will form part of the 20,000km national high-speed rail network, and is expected to massively improve the connectivity between Hong Kong and many mainland cities, especially those in southern Guangdong province.

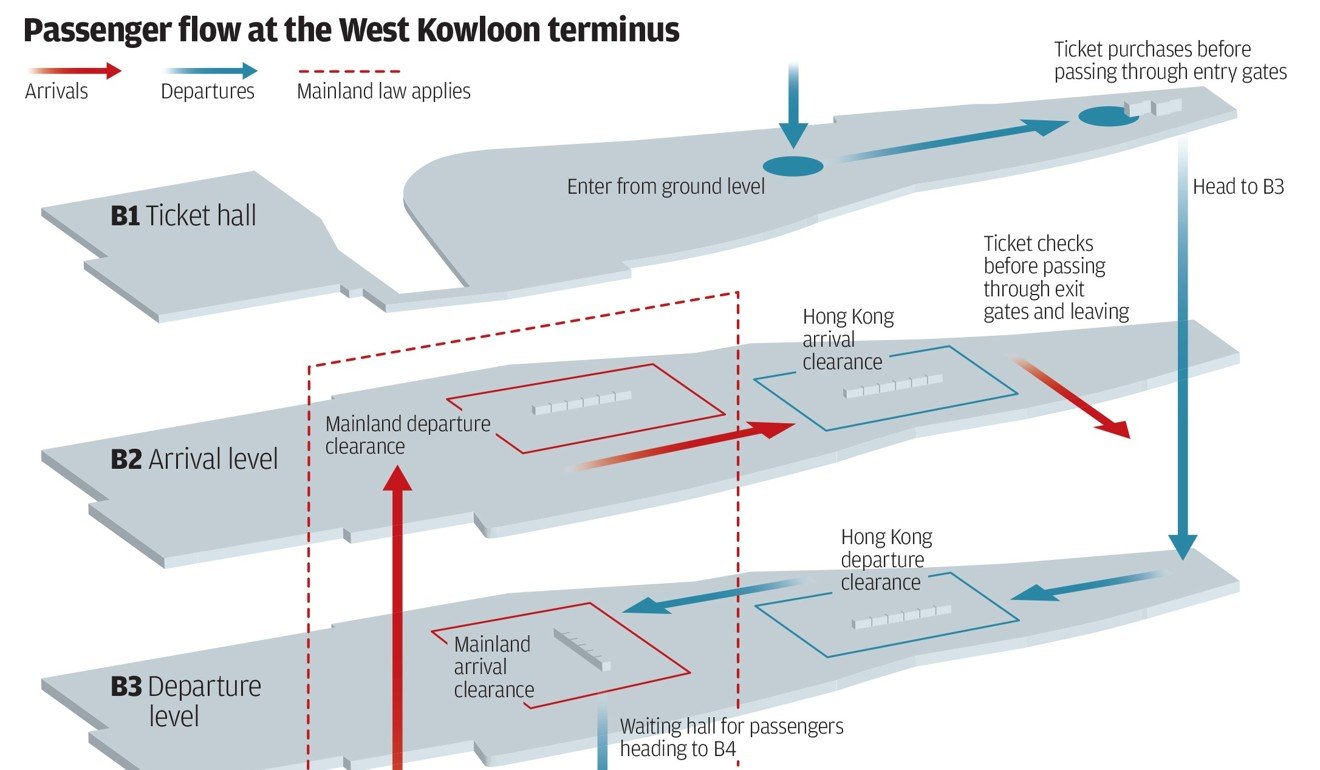

Hong Kong officials argued that to fully realise the potential and economic benefits of the much-delayed railway, it is essential to lease a quarter of the West Kowloon terminus to mainland authorities.

Joint checkpoint at railway terminal touches a nerve despite success of Shenzhen model

They said it will allow travellers to have their travel documents checked by both Hong Kong and mainland officers in one terminus, rather than asking travellers to be checked separately by mainland officers before or after they enter Hong Kong.

Security officials also argued that rather than only enjoying jurisdiction over immigration and custom matters, mainland officers should enjoy almost full jurisdiction in the “mainland port area” at West Kowloon. It will make sure that the terminus would not become a paradise for mainland fugitives, they said.

2. What was its legal and constitutional basis, according to Hong Kong officials?

Asked how Hong Kong can lease out land to mainland authorities, Yuen said Article 20 stated that Hong Kong “may enjoy other powers granted to it by … the standing committee of the National People’s Congress”.

3. What did critics say about the legal basis?

Hong Kong’s pan-democratic camp opposed the joint checkpoint plan, which it said contravened the Basic Law.

On Yuen’s reference to Article 20, Democratic Party founding chairman Martin Lee Chu-ming, who sat on the committee that drafted the Basic Law, said the article was intended “to grant Hong Kong more powers in its autonomy”, not giving it the power “to castrate itself”, or to surrender its autonomy in any part of the city.

Civic Party barrister and legislator Tanya Chan also said the checkpoint plan, which allows mainland laws to be applied in the terminus, contravenes Article 18 of the Basic Law.

High-speed rail link border checkpoint in Hong Kong ‘has public support’ says Carrie Lam

Under that article, no mainland law shall be applied in Hong Kong except for those relating to defence, foreign affairs and “other matters outside the limits” of the city’s autonomy. Mainland laws must also be listed in the Basic Law’s Annex III before they can be applied in Hong Kong.

However, Hong Kong officials argued that after the “mainland port area” is leased to the mainland, it will be regarded as outside the city’s boundary, and Article 18 would not apply.

It was not just pan-democrats who had reservations about the applicability of Article 20.

Last month, Peking University law professor Rao Geping, a key member of the Basic Law Committee under the NPCSC, said the article was for Beijing “to give Hong Kong an additional power”, not for Hong Kong to lease land to mainland authorities.

But Rao also said the plan should be supported as “mutual rental” of land to promote economic and transport cooperation was normal.

4. What other articles in the Basic Law were suggested as the legal basis?

Pro-establishment legal experts had suggested that instead of relying on Article 20, there is a series of provisions, including Articles 2, 7, 22, 118, 119 and 154, that can be used as the legal basis of “co-location”.

Former Bar Association chairman Ronny Tong Ka-wah, who sits on the Executive Council that advises the Hong Kong government, argued that Article 2 offers the legal foundation for the joint checkpoint arrangement.

Under the article, the NPC authorises Hong Kong “to exercise a high degree of autonomy and enjoy executive, legislative and independent judicial power”. He said it reinforced the proposition that the city’s government has the power to lease land to authorities, including those from the mainland.

Speaking before the NPCSC meeting on Friday, Basic Law Committee member Maria Tam Wai-chu argued that Articles 118 and 119 should apply.

Under Article 118, the Hong Kong government “shall provide an economic and legal environment for encouraging investments”, while under Article 119, it shall formulate policies to promote various trades such as tourism and transport.

Basic Law Committee vice-chairwoman Elsie Leung Oi-sie, a former secretary for justice, previously said Hong Kong could lease part of West Kowloon to the mainland because under Article 7, Hong Kong’s land and natural resources belong to the state.

The Hong Kong government is responsible for land management, use and development, as well as “for their lease or grant to individuals, legal persons or organisations”, she said, citing Article 7.

Speaking after the first day of the meeting on Friday, Leung added that the legal basis of the checkpoint plan may rest on Article 22 and 154 as well.

Under Article 22, no mainland authority “may interfere in the affairs” which Hong Kong administers on its own. If any mainland authority needs to set up offices in Hong Kong, it must obtain the local government’s consent and Beijing’s approval.

Under Article 154, Beijing shall authorise the Hong Kong government to issue passports and travel documents, as well as to apply immigration controls on travellers and foreign states and regions.

Leung argued that Articles 22 and 154 “mentioned that we can negotiate with mainland authorities on the procedure for mainland officers to come to Hong Kong … and that we can decide on the immigration controls on travellers.”

The former justice chief also said that there would not be any single article that supports “co-location” because no one could have foreseen China’s high-speed rail development when the Basic Law was drafted in the 1980s.

“‘One country, two systems’ is for national unity, territorial integrity, and safeguarding Hong Kong’s prosperity and stability … co-location complies with this policy,” she said.

5. What was the latest development?

Last Thursday, pro-establishment heavyweight Jasper Tsang Yok-sing dropped a bombshell by saying that local officials should admit that the Basic Law did not provide the legal basis for the controversial joint checkpoint arrangement.

“The Basic Law has left no room for implementing the ‘co-location’ arrangement,” the former Legislative Council president wrote in his column in a Chinese-language newspaper. He said the government should not try to find justification from Basic Law clauses but instead admit that the situation was beyond the imagination of law drafters some 20 years ago.

6. What now?

Last month, Hong Kong Chief Executive Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor signed a deal with Guangdong governor Ma Xingrui to set up a mainland port area at the West Kowloon terminus of the Guangzhou-Shenzhen-Hong Kong Express Rail Link.

With the NPCSC’s endorsement on the issue on Wednesday, the Hong Kong government will move towards the final and perhaps most challenging and uncertain step: to push local legislation through the Legislative Council by mid-July to implement the system.

Earlier in December, the pro-establishment bloc in Legco succeeded in having the legislature’s rules amended to curb filibustering, despite strong opposition.

But opposition lawmakers, including localist Eddie Chu Hoi-dick, have vowed more extreme action to block the government’s draconian legislation.

It remains unclear whether the legislation will be passed in time, or whether there will be further delays to the opening of the express rail.