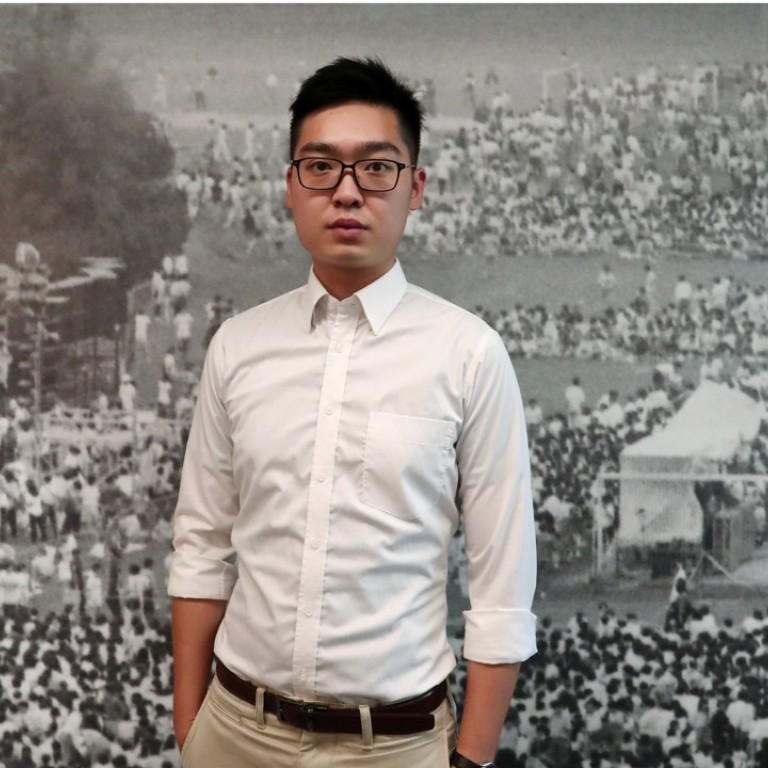

Why does the Hong Kong National Party rile Beijing so much, and just who is Andy Chan Ho-tin?

In two years, Chan has navigated the city’s politics into uncharted waters, not once but twice. But why are the authorities acting now and what has alarmed them?

Long before he was caught in the political maelstrom of the moment, Andy Chan Ho-tin spent his Saturdays trying to outdo the singing aunties of Mong Kok.

But the young graduate was jostling with the boisterous buskers in the area’s famous pedestrian zone to the beat of his own ideological drum.

If the aunties were off-key in their melodies, as was often the case, Chan was low-key in his methods.

Some time between 2015 and 2016, Chan and his clutch of 10 friends distributed leaflets to the crowds each Saturday evening and took turns speaking into their portable microphones, their voices drowned out by the din. But they were undeterred.

But no one seemed to be buying the idea. After a year of not making much progress and even fewer converts, Chan decided to change his strategy.

CY Leung dares FCC to surrender lease in row over Andy Chan talk

“The impact was way too small,” the Polytechnic University graduate, now 27, recalled of the sultry Saturday evenings spent fighting for the attention of indifferent shoppers.

“What would be more influential than forming our own party and running for elections? Someone had to break this taboo, I felt,” Chan told the Post in a recent interview.

From that brief foray into the limelight, Chan retreated into obscurity over the ensuing months as others more well known were disqualified from Legco or from even contesting.

Students vow to revive independence bid in Hong Kong schools

Police claimed what the HKNP did – such as “propaganda” through media channels, “school infiltration”, street booths, alongside Chan’s quashed bid to run in the Legco polls and his declarations on the use of violence – was tantamount to an “imminent threat” to national security and public safety.

The party has until September 4 to show cause why it should not be banned.

In two years, Chan has navigated the city’s politics into uncharted waters, not once but twice – forming a party pledging to take up the cudgels against the Communist Party of China to separate Hong Kong from the motherland, and now being possibly the leader of a banned political party. Just who is he, anyway? And why are the authorities so alarmed? Why act now?

Andy Chan, rebel with a cause larger than Occupy

Before his Mong Kok days, Chan was one of the thousands of students who took to the streets during Occupy. An emotional low point for him – and many others – was seeing police use tear gas on fellow Hongkongers. Chan decided there and then that there was no turning back.

Like the others who continued to press on after Occupy ended, Chan said it was during those nights out on the streets that he had the epiphany that the only way for the city he loved to be free to do what it wanted was to secede from China.

“I was completely apolitical before. I didn’t know anything about universal suffrage when I took part in the movement. I came out only for the feeling that Hongkongers were being bullied by China – it was more about an identity issue,” he said.

He recalled the confusion he felt one day in the occupied zone in Admiralty, when several protesters near him suggested they tear off a national flag that was on a truck.

Government must pay legal costs for Joshua Wong and two allies

“I was puzzled at the time. I saw no reason to do that as we were only there to fight for democracy,” Chan recalled. “But soon after I realised Hong Kong was denied democracy not because of the local government, but China. That was when I began thinking of cutting our ties.”

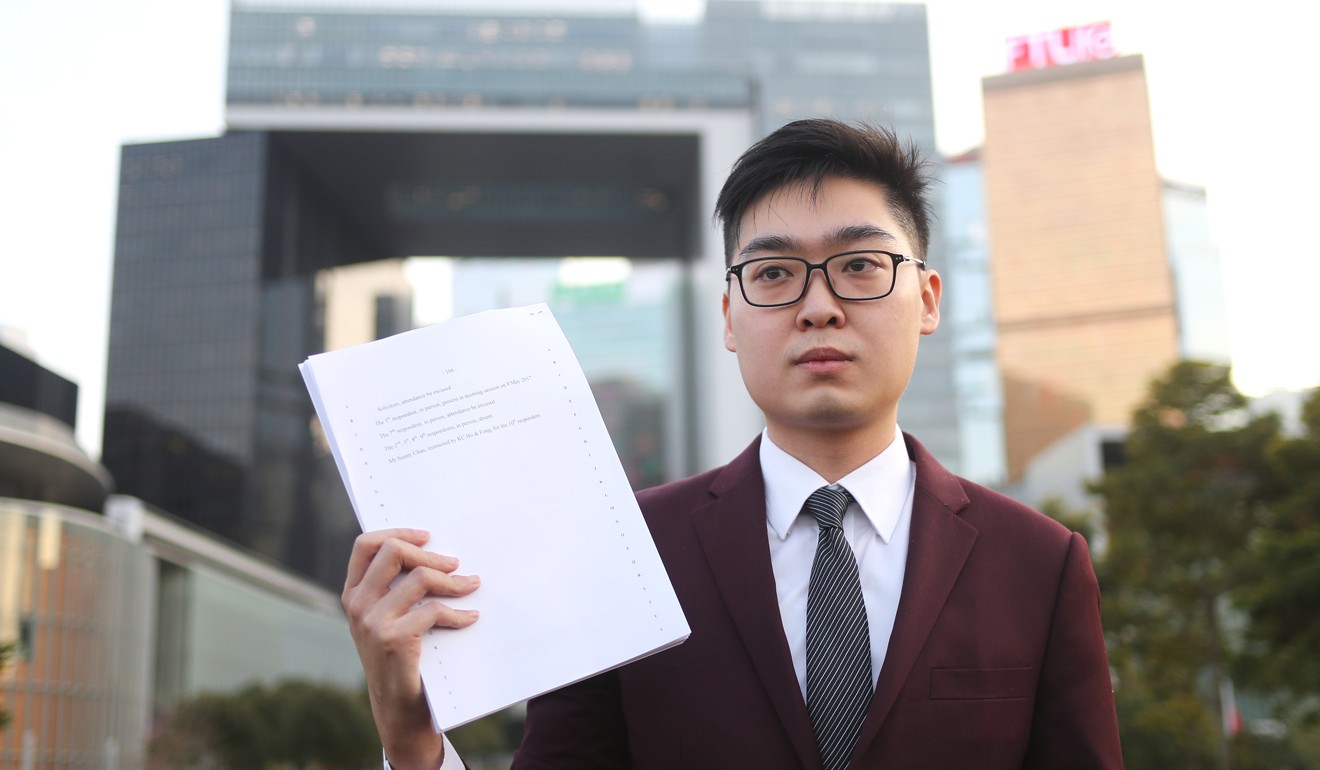

In March 2016, Chan called a press conference at a Tuen Mun factory office of about 1,000 sq ft – an impressive size given he was the only one present – to announce the setting up of the HKNP. He pledged to use “whatever effective means” to achieve their cause.

I realised Hong Kong was denied democracy not because of the local government, but China. That was when I began thinking of cutting our ties

“Staging marches or shouting slogans is obviously useless now. Regarding using violence, we would support it if it is effective to make us heard,” Chan declared then.

“Effective means” also meant beating up someone to “vent his anger” at lawmakers, he went on to suggest on a radio show later that week.

“When someone asked [the legislature] to approve the funding request concerning hundreds of millions of dollars, it would be great if we could at least punch him,” he said. “We might not be able to block [the funding request] but at least we could vent the anger by hitting him.”

Another unnamed member of the group said on the same radio show they could emulate opposition parties in Kosovo by releasing tear gas inside the chamber.

Since then, only Chan and HKNP spokesman Jason Chow Ho-fai are known to the media. The group claims to have 30 to 50 members but has declined to produce them, citing fears for their safety. Some of them had already become victims of surveillance, Chan claimed in the interview with the Post. Chow could not be reached for an interview. When the Post visited the office unit, which property agents estimated costs about HK$7,000 a month to rent, the door was locked and junk mail was stacked on the grilled gate. Chan said the unit was borrowed from a friend.

From day one, Chan has insisted members fund the party’s operations from their own savings. In 2016, he claimed the party had no more than HK$100,000 (US$12,820) in its accounts.

Why Hong Kong pro-independence party should be banned

When the party was formed, pro-Beijing media commentators tripped over themselves trying to condemn Chan and company. One sneered that it was “a revolution launched by a group of mentally ill patients”. Another called them clowns.

After one controversial attempt to hand out fliers outside secondary schools and a public rally that same year, the party remained largely low-profile. Chan went to Taiwan and Japan for exchange tours.

Despite attacks from pro-Beijing media over his Taiwan visits, police have maintained the case against the HKNP remains focused on it posing a threat to national security, rather than its connections with foreign political outfits, which potentially could trigger a ban under the same Societies Ordinance.

Meanwhile, Chan claimed that even as they shifted focus to building overseas connections because of increasing restrictions in Hong Kong, the party had throughout remained active in the city.

Chan emphasised that no money changed hands between the Taiwanese organisations and his party, saying at most the civil groups had subsidised his trip.

Pressed on how he would go about pushing for independence when it seemed a futile cause, Chan said he would still want to foster a sense of identity among Hongkongers and, with time, persuade them that if they cared for democracy then they should seek to resist the Chinese Communist Party’s control as it would not tolerate democracy for the city. Asked if he was making it tougher for others with more modest plans to keep the “one country, two systems” policy firmly in place, he shrugged it off as the price to be paid.

With the exception of pro-Beijing media occasionally hectoring them, Chan had been ignored by just about every other politician in town – until now.

A calculated move?

Pan-democrats and legal scholars have slammed the police’s case, arguing strenuously that the move would put Hongkongers’ freedom of association and expression at risk.

Many are baffled that the authorities have decided on a sledgehammer approach to crush an almost inactive, isolated and barely influential party at a time when any semblance of pro-independence sentiment is on the wane.

One look at the mild-mannered, fresh-faced Chan and the cognitive dissonance that he could pose a security threat is apparent.

Things, however, are not so simple and the political calculations far more intricate.

Of course, Chan provided easy fodder with his talk on violence. Even if empty, security agencies will see it as a red flag to future action.

For some pan-democrats, the proposed ban is a move designed to force them to denounce pro-independence groups unequivocally and draw a firm red line not just on action but, more worryingly, on speech.

Many are therefore finding themselves having to tiptoe around the issue, balancing between speaking up fiercely against the ban but also at once stating up front their anti-independence stance. It is a nuanced position that has just ended up making them look mealy-mouthed, some indicated to the Post.

So, while they have forged a united front to condemn the ban which they argue will erode the city’s freedoms, many laced their salvoes with solemn statements about being against the independence movement. Worse than that, the ban could be the Trojan horse to assail other players in the pro-democracy camp, they warned.

“The authorities are trying to portray a picture that the notion of Hong Kong independence has won a lot of support here as an excuse to further crack down on the pro-democracy bloc,” said a lawmaker who spoke on condition of anonymity.

“We have to speak up for the party as the government is trying to set a precedent in using the same trick to ban others in future, but at the same time we have to be very careful to avoid being framed.”

Young Hong Kong voters give by-election a miss in droves

The conundrum has forced the camp to be cautious. At a protest against the ban held last month, only six lawmakers showed up among the hundreds of others – a small demonstration by most standards.

The lawmaker described the authorities as “very cunning” by targeting the HKNP. Being neither active nor popular, they know they can act with impunity as there will be little public support for the party.

The question being asked nervously in their circles: who will be next?

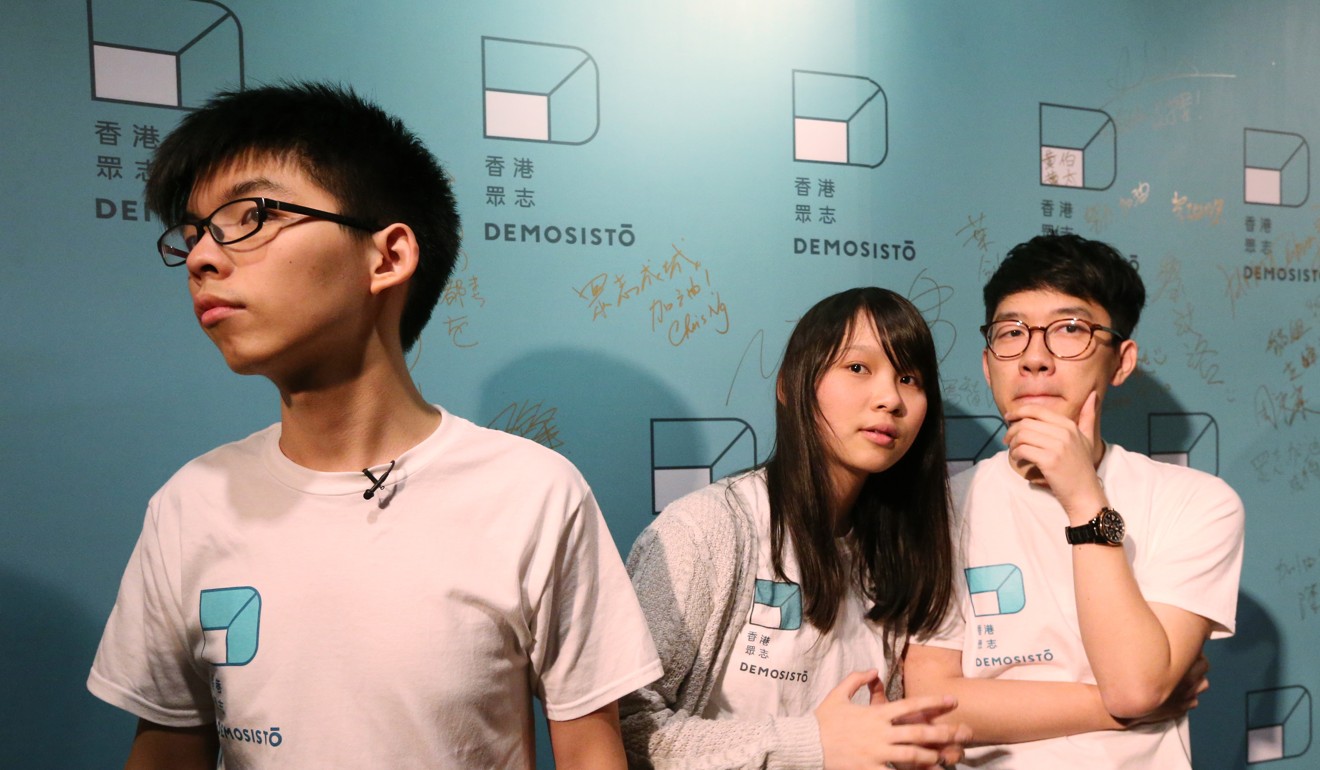

Chan said he believed Demosisto, the political group co-founded by Occupy student leader Joshua Wong Chi-fung, could be the next target, just ahead of district council elections due next year.

Political watcher Ma Ngok, of Chinese University, said the proposed ban was coming at a time where Hongkongers were getting used to the government’s tougher approach to dissent.

He cited a 2013 journal article by Alberto Simpser, in which the Mexico-based political scientist argued that while government’s manipulation in elections would trigger public backlash, the “legitimacy loss” it suffered declined time after time as citizens’ determination to resist wore thin.

“The administration probably found the ‘legitimacy loss’ to be triggered by the proposed ban would not be huge,” he said.

In other words, fatigue has set in and resistance will be futile.

But another stark fact about the timing is this – doing nothing was not an option for the Hong Kong government and dithering and delaying any action was also not possible. It had to act because the directive came from the top. In July last year, when he visited the city, President Xi Jinping warned Hongkongers against crossing the “red line” of undermining Chinese sovereignty even as they disagreed with the central government issues.

“Although some Hongkongers might find the HKNP insignificant, Beijing has zero tolerance over any attempts to take advantage of the ‘two systems’ to harm the ‘one country’,” said Tam Yiu-chung, the city’s sole delegate to the National People’s Congress Standing Committee, the country’s top legislative body.

“Such a bid has to be suppressed, no matter if it has prevailed or not.”

And Chief Executive Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor has had no choice but to act, he said.

A slippery slope

Scholars said the proposed ban had once again underscored the difficulties of implementing “one country, two systems” – the guiding principle for Hong Kong until 2047.

Observers suggested that the latest move showed the authorities were now willing to resort to what critics have labelled “draconian laws” which they had resisted from doing in the past.

Two past incidents of such restraint are noteworthy. The first was during the lobbying by the pro-Beijing camp for the Falun Gong to be banned in Hong Kong after the sect was prohibited in mainland China in 2001.

Authorities reportedly studied the possibility of crushing the sect under the Societies Ordinance – which states such a ban could be justified in the name of national security or public safety – but they did not push ahead after finding no evidence of illegal action.

Hundreds take to streets in support of pro-independence party

Second, during the 2003 debate over the aborted national security law, the city’s officials tried to soothe the public by repeatedly emphasising that speech alone – in the absence of violence or illegal acts – would not be prosecuted. The bill was eventually shelved after half a million Hongkongers took to the streets.

But with the proposed ban on the HKNP, police are asking for “preventive measures” before any act or evidence of violence.

Johannes Chan Man-mun, former law dean of the University of Hong Kong, argued that given there was no clear definition of “national security” or “territorial integrity” under the Societies Ordinance, these concepts should be narrowly defined lest they be abused to be a catch-all to curb all manner of dissent. Therein lay the danger of the slippery slope of citizens’ freedom of expression being restricted, he warned.

If not properly defined, there was the risk that “even speaking for independence of Taiwan, Tibet or even saying the Diaoyu Islands should belong to Japan, could very well fall under the definition in the law”, he said.

Chan also warned that the authorities’ move could put the court in the invidious position of having to deal with what is meant by “national security” if it is asked to decide such a ban is legitimate. What happened if the court chose to disagree with the ban? Would Beijing then intervene by interpreting the Basic Law, he asked.

Maria Tam says Beijing did not intervene over Andy Chan speech

Senior Counsel John Reading, the city’s former deputy director of public prosecutions, said the case against the HKNP was “a bit of a stretch” as there was no treason or sedition law in force.

“Triads are banned because they are put together for an illegal purpose, [such as] drug trafficking, gambling [and] all sort of things,” Reading said.

He cautioned that it might be hard to argue the HKNP’s purpose had breached any existing criminal law.

But Grenville Cross, previously the city’s director of public prosecutions, said the Societies Ordinance had defined “national security” in terms of safeguarding “the territorial integrity and the independence” of China, and thus the concerns of the police over the HKNP could not be dismissed as illusory.

“No civilised society, however great its commitment to democratic rights, can be expected to tolerate organisations which directly threaten its national security or the safety of its people,” he said, citing Britain’s effort in 2016 to proscribe National Action, a neo-Nazi group, and the decision of South Korea’s constitutional court to ban the United Progressive Party, which was accused of supporting North Korea-style socialist systems and posing a threat to the country’s liberal democracy.

Opposition losing support of public opinion

The latter ban, however, sparked criticism in South Korea with Amnesty International arguing security concerns must never be used as an excuse to deny people the right to express different political views.

Cross, however, argued such a limitation was observed by international civil rights guarantees, which recognise freedoms and rights are not absolute.

Maria Tam Wai-chu, vice-chairwoman of a committee advising Beijing on Hong Kong’s mini-constitution, also said there was sufficient evidence from their activities that the HKNP was “plotting something” and therefore the ban was legally justified.

For now, however, another side battle has erupted to put September 4 in the background while all eyes turn to another date – August 14.

Leung charged that the club’s move to invite Chan “had nothing to do with press freedom”, and, upping the ante, he suggested the FCC had its leased premises by the generosity of the government and most private landlords would not welcome tenants who hosted such speakers. Why should the Hong Kong government be any different, he asked, taunting the club.

Ironically, even as the government maintains drawing the red line on separatists is not about curbing freedom of speech, the sideshow with the FCC is threatening to reduce the issue to just that.

Chan can be expected to protest his stance at the talk, just as he insisted to the Post he had done nothing wrong in crossing the red line.

He declined to reveal his next moves but admitted going underground might be inevitable. Now an employee of an engineering firm, he said he had been stalked for some time and had received several dubious calls the night before the police visited his home last month to inform him of the ban. He believed the callers might have wanted to track his location. His family members, including his mother, sister and her boyfriend, also received calls allegedly from authorities wanting to confirm their residential address.

Shrugging his slight shoulders, the 27-year-old declared that the burden of pushing for the cause of independence was not his alone to bear.

His failure was everyone else’s, he suggested. “Many people said fighting for independence is not a viable option … but actually fighting for democracy in Hong Kong is equally impossible as the central government would like to exert control on everything,” he said.

Additional reporting by Alvin Lum